As work begins to demolish some of the main structures on the Redcar steelworks site, a personal reflection on whether the blast furnace is a blot on the landscape or an important piece of heritage that needs to be preserved…

FIFTY years ago, me and my mate Paul “Moggy” Morrison sat on top of Eston Hills and looked down at the vast industrial landscape, with white clouds billowing from the cooling towers, and flaring stacks spitting out flames like giant Bunsen burners.

I remember suggesting that it was horrible, but Moggy disagreed: “Nah,” he replied, calmly. “That’s our bread and butter – it’s beautiful.”

Our dads were steelworkers, among the thousands who earned a living at the Teesside plant that stretched from South Bank to Redcar, beyond the chemical complex of ICI, as we looked down from the hills.

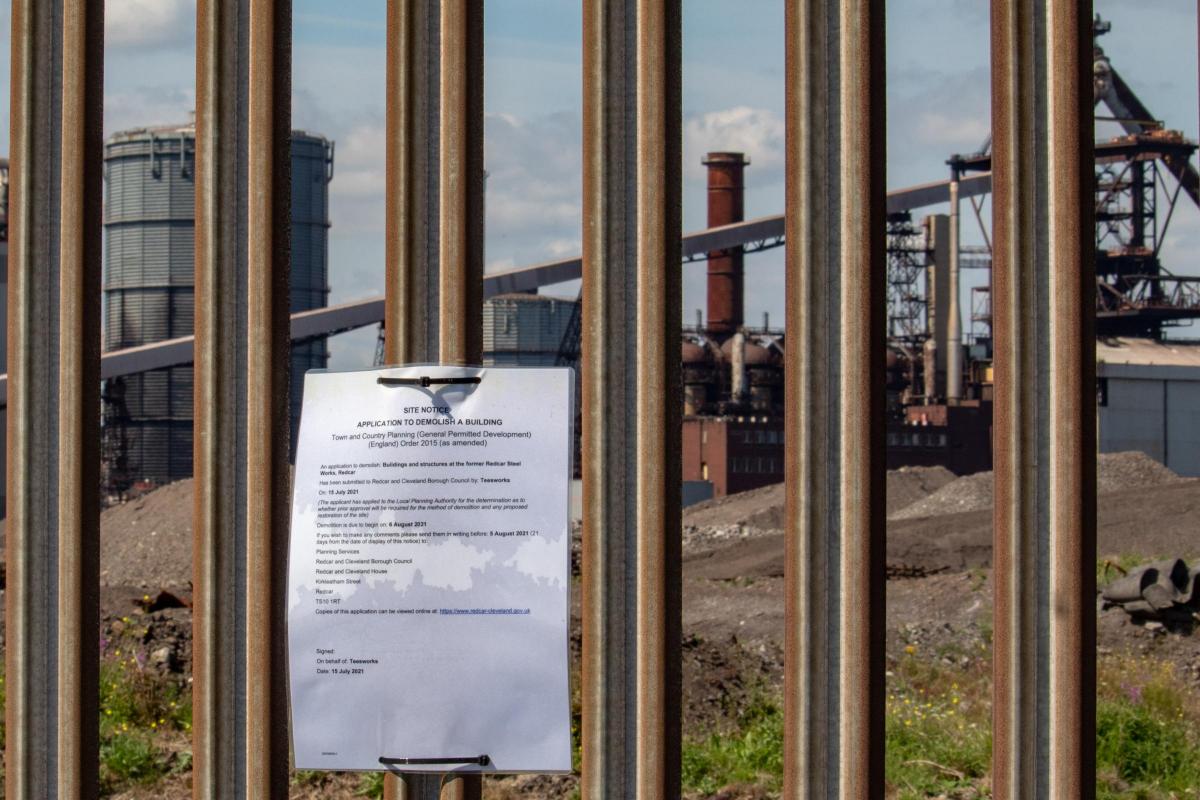

I’ve never forgotten Moggy’s words, and they feel especially poignant now, half a century on, as demolition work gets underway that will forever change the landscape that was the backdrop to our childhood.

The huge chimneys of the Basic Oxygen Steelmaking (BOS) plant have already come down and, within 12 months, the site – including the iconic blast furnace, the heartbeat of it all – will be gone, making way for a new era based around green industries, such as carbon capture and storage, hyrdrogen, and offshore wind.

And yet, the debate surrounding the demolition of the blast furnace has been passionate. Some have described it as “industrial vandalism” and even “robbery of our heritage” – demanding that the blast furnace be artistically preserved. Others can’t wait to see the removal from the skyline of what they, unromantically, consider to be an ugly blemish.

Amid those arguments, I felt a sudden urge to visit the site before it’s too late – as if paying my last respects to the body of a loved-one before their funeral. An evening walk was, therefore, called for at South Gare, a stark area of reclaimed land that offers the most intimate views of the blast furnace.

Industry meets nature at South Gare, with just a spiky metal fence, and a pot-holed road, separating the steelworks’ carcass from sand dunes teeming with wildlife.

Up past the blast furnace, Paddy’s Hole is the name given to a small harbour, in memory of the gangs of Irish labourers who built it out of slag.

Opposite, on the fringe of the dunes, are the higgledy-piggledy assortment of green fishermen’s huts that attracted the producers of Sky Arts Landscape Artist of the Year, in 2017.

The road might be marked “private”, but few locals take any notice of the signs, and it’s long been a popular route for fishermen and walkers.

One of those striding through is Joe Livingstone (pictured below), who has made it part of his daily exercise routine for the past 11 years. Back then, he was 22 and half stones and made a life-changing decision to sell his security business and start walking.

Since then, he’s lost nine and a half stones and, during lockdown, he’s walked 18 and half miles a day to keep his weight down. That includes parking his car at Peddlers bike shop, on the edge of Redcar, and walking up through South Gare and back.

Joe’s dad was a former professional footballer, also called Joe Livingstone, who was understudy to Brian Clough at Middlesbrough, and died in 2009. He was known for his physical strength and, after playing for the Boro, Carlisle and Hartlepool, he grafted at Tees Dock.

So, what does Joe Livingstone junior reckon to Teesside’s heritage being razed to the ground?

“It’s sad but it’s time for it to go, isn’t it?” he replied. “It’s an important part of our history but it’s had its day. It’s time for a new generation now, and it’s exciting that the new jobs are coming.”

Whatever the future holds, the South Gare will always be a special place for Joe. “I just love it here – there’s something about it that’s relaxing,” he added. “You can feel the stress leaving you and you never know what you’re going to see – we’ve just seen a massive owl swoop past.”

Joe’s mate, who preferred not to be named, agrees that the time has come to let go, adding: “The great thing about Teesside is you’re 15 minutes from everywhere. Fifteen minutes from the sea, 15 minutes from the hills, 15 minutes from industry, 15 minutes from glorious countryside. We’re dead lucky, aren’t we? That won’t change.”

Dave Cocks (pictured below), well-known as one of Redcar’s longest-serving lifeboat volunteers, has a long, proud history at the Redcar steel plant. As a kid, he rode his bike through the Warrenby Works to play on the old World War Two defences.

“It was always part of my life, seeing the glow of the steel that was being made,” he recalled.

After graduating from university, he joined the British Steel Corporation in 1978, and rose through the ranks, ending up as technology manager at the Redcar plant. His saddest duty was to oversee the blast furnace shutdown as the demise began in 2010.

With 32 years as a Redcar steelman behind him, surely few people can be as well qualified to have a view on the past and the future. “It’s heart versus head,” is his take on it.

“My heart says a whole generation is used to seeing that iconic silhouette on the skyline – not just steelworkers, but the whole community.

“But, if they’d resisted change 170 years ago, we wouldn’t have had a steel industry, and we shouldn’t resist change now. The blast furnace is pretty rotten, and it wouldn’t be practical to keep it, so if it has to come down, so be it.”

That said, Dave insists the past mustn’t be forgotten. The authorities have pledged that the history of the site will be documented before it goes, with artefacts housed in a museum, and Dave would also like to see a permanent exhibition of photographs and paintings of the site.

“We shouldn’t be afraid of where we’re going, but we should always remember where we came from, and what made us,” he said.

I’ve lost touch with my childhood friend Moggy, but I’m guessing he would agree. It was our bread and butter, beautiful in its own way, but it’s time to look beyond the steelworks.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel