Monday is the 200th anniversary of one of the most important events in local railway history which took place in a kebab shop

ON the evening of April 19, 1821, two strangers approached the front door of Edward Pease's home in Northgate, Darlington.

They came from wildest Northumberland and had set off early that morning by horse for Newcastle. At Newcastle, they caught a stagecoach bound for Stockton "by nip" – tipping the driver rather than paying the fare. From Stockton, they walked 12 miles across farm and field, following the path that was proposed for the Stockton and Darlington Railway, until they came to Mr Pease's home on the northern edge of town.

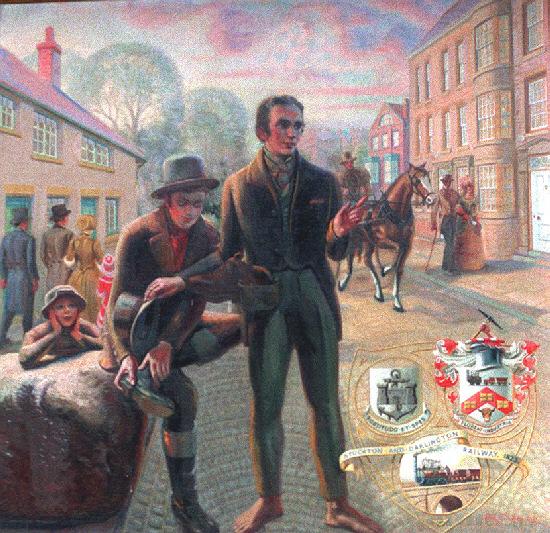

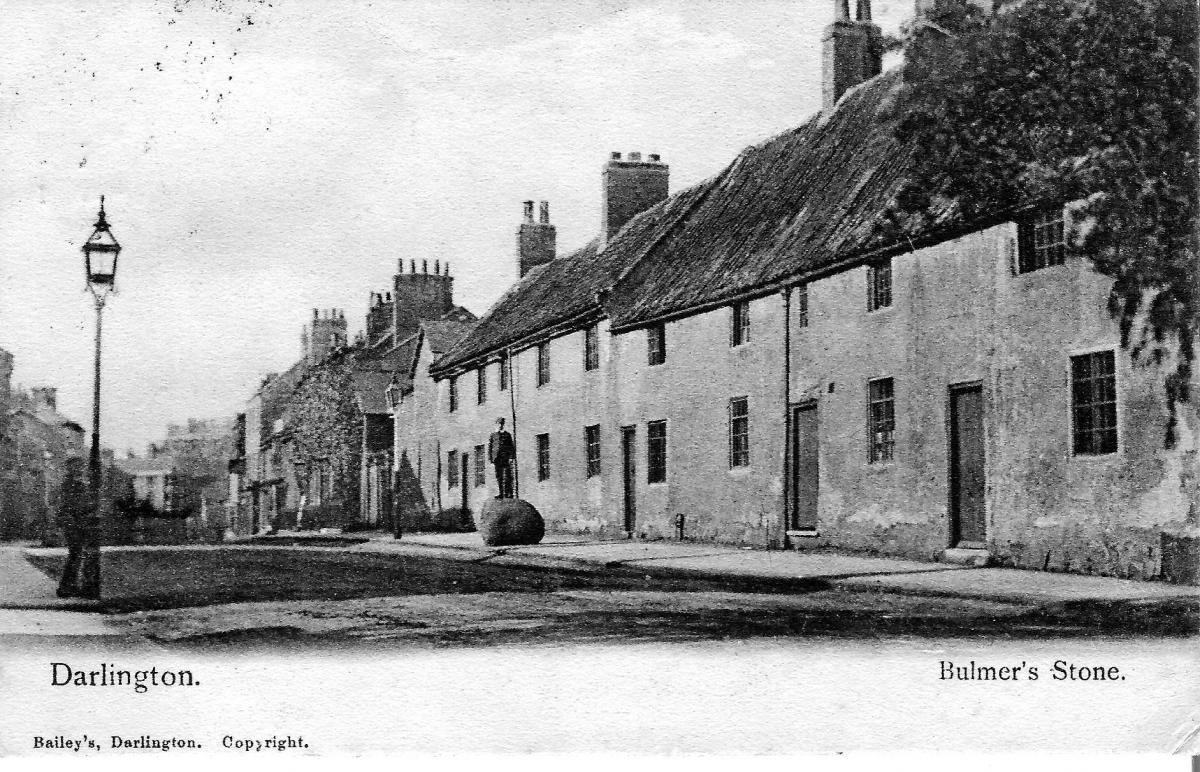

Opposite was Bulmer's Stone – a large local landmark – upon which they rested.

One version of this story says they had walked barefoot to Darlington, to save their shoeleather on the walk from Stockton, and so on the stone they put their shoes back on before going to Mr Pease's house.

Another version says that they had walked from Stockton in their shoes, which had become so muddy, they thought it best to remove them on Bulmer's Stone before knocking on Mr Pease's door.

Barefoot or not matters not: Mr Pease was not at home to cold callers and told his servant to send them away. He was upstairs, awaiting news from London where King George IV had that day given his Royal Assent to the Stockton and Darlington Railway Bill, which gave Mr Pease Parliament's permission for him to build "a railway or tramroad" across the south Durham countryside.

But, after a few minutes, Mr Pease had a change of heart. He inquired of his servant if the men were still there.

Fortunately, the servant had taken pity on the Northumbrians and offered them some refreshment in the kitchen after their long journey.

So Mr Pease joined them in the kitchen, which is now the front of the Best Kebab 1 shop, next to Cuisine Marmaris, another kebab shop, and Domino's pizza parlour. He perched on the kitchen table, and introduced himself to the two visitors sitting on the cream and pink bench sofa, which is now in the Head of Steam museum.

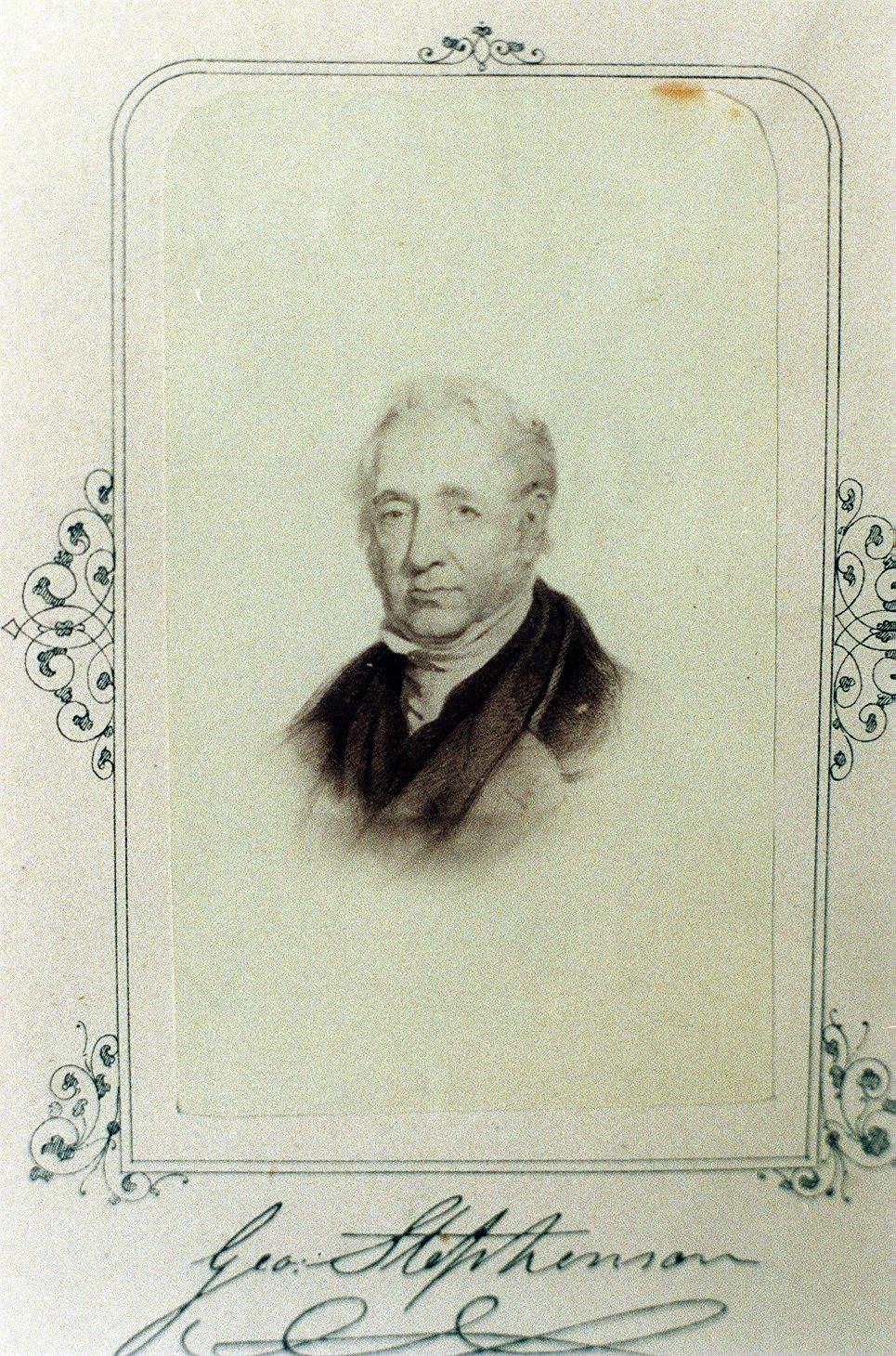

They were, they said, Nicholas Wood, the view (or manager) of Killingworth Colliery, and George Stephenson, the colliery engineer who at that time was also designing the eight-mile private railway at Hetton (which celebrates its 200th anniversary next year).

They wished to talk about the 26-mile public "railway or tramroad" that Mr Pease was hoping to build from the south Durham coalfield to the seaport at Stockton.

Stephenson said he agreed with Pease that the project should be a "railway" – it should have protruding rails, laid on sleepers, around which the wagon wheels would wrap, rather than a "tramroad", which was a groove in the ground into which the wheels slotted. Pease was probably in a minority among the railway pioneers in arguing for a railway.

Perhaps more importantly, it was here in the kitchen that Stephenson convinced Pease that rather than having horses pulling the coal wagons on the railway, it should be a new-fangled, moving steam engine – the word "loco-motive" had not yet entered the English language – that should provide the power. Stephenson said how he'd built an engine at Killingworth that was worth 50 horses.

Pease was probably already inclining towards a technological approach, but the rest of the investors in the project were not – and so the emblem of the railway shows a horse doing the donkey work.

As the meeting in the kitchen drew to a close, Stephenson, a rather broad and unsophisticated Northumbrian, turned to the fashionable art of phrenology – reading the shape of a person's skull to determine what abilities they have.

He said: "I think sir, I have some knowledge of craniology and from what I see of your head, I feel sure that if you will buckle to this railway, you are the man to carry it through."

Pease, who certainly did not believe in such fancies, replied in his Quakerish way: "I think so too. I may observe to thee that if thou succeed in making a good railway, thou may consider thy fortune as good as made."

And with that, the meeting terminated. Pease retired to bed and Wood and Stephenson were turfed out into the Northgate night. It was now so late that they had missed the last stagecoach home and, as no one had yet invented the railways, they were forced to walk. They managed 18 miles until Wood collapsed from exhaustion a couple of miles short Durham, and had to be carried to a roadside inn for the night.

And so Pease, the father of the railway, had met Stephenson, the father of the locomotive.

Or so the story goes.

And it is a good story, captured by the large painting in Darlington council's collection, although much of it has been much elaborated and distorted over the course of time. Francis Mewburn, the otherwise reliable first railway solicitor, embroidered the barefoot bit and Wood himself added his collapse as if to prove that he was present at the birth of the modern railway.

It is inconceivable that Stephenson was a complete stranger when he knocked on Pease's door that evening. As early as February 1819, the Darlington railway pioneers were writing about getting a "Mr Stephenson of Sunderland" involved in the project.

And Pease must have been at least aware of the latest transport innovations in his own district: the Hetton Colliery railway was the longest then attempted, and just days before the meeting, Stephenson had used locomotive power at Killingworth to haul 20 loaded coal wagons up a one-in-288 gradient "with an amazing degree of rapidity which beggars description".

It does seem as if Stephenson and Wood were on a charm offensive that day. They went to Stockton first to meet solicitor Leonard Raisbeck, who was supporting the Darlington project, and then came through to see Mr Pease, probably with an appointment. Perhaps the only truthful bit is that their shoes could have been a bit muddy and so rather than ruin the great Quaker millowner's carpet, they knocked them off on the nearest obstacle – Bulmer's Stone.

But the meeting is vitally important. As The Northern Echo put it in its 1875 history of the S&DR: "The Railway Projector and the Railway Engineer had met, with results the bruit of which the world, with its thousands of snorting locomotives, is ringing to this day."

Pease had met Stephenson; the money had met the ingenuity. Most crucially of all, steampower was now going to be employed along the length of the line. All the latest technologies of the day were going to be brought together on an industrial scale to create the first modern railway.

All railways the world over can trace their beginnings to the kebab shop on North Road.

For years, Memories has been banging on about how more should be made of this great story which is set in a building that still stands – although much changed and, apparently, in poor condition. Indeed, a decade ago, we noted how workmen replacing the roof had shovelled out a skipload of pigeon guano from one of the upstairs rooms – perhaps even Mr Pease's bedroom – but unfortunately, they'd failed to secure the window probably, and so the pigeons moved straight back in, with a nice watertight roof over their heads.

Now, at last, in recent weeks, Darlington council has bought Pease's house with a view to incorporating it into the 200th anniversary celebrations and using it to regenerate the North Road area. More details to come.

IN Edward Pease's day, this edge-of-town property had a long, well stocked garden down to the river, perhaps with an ornamental bridge over the Skerne. Now behind the house is a tarmacked car park.

He had bought two houses here for £600 in 1799. He rented out the right-hand property, which is now Domino's pizza parlour, and lived in the left-hand one: his kitchen was on the front where Best Kebab 1 is today and his adjoining sitting room was where Cuisine Marmaris is.

The front of the property was altered unrecognisably in the 20th Century as the building got swallowed up by the town centre. In 1866, owner Thomas Hodgson placed a classical facade on the block and turned it into four shops.

In 1909, butcher Frederick Zissler carved his own premises out of part of it – although he did, at least, mark its history by having a curious plaque put up on it with irrelevant information and date on it. This is now the Best Kebab 1 takeaway.

And in 1923, a new shopfront was added to the rest of the block for haberdashers J Hartas Stephenson, obliterating any sense that this was building in which the world was changed.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel