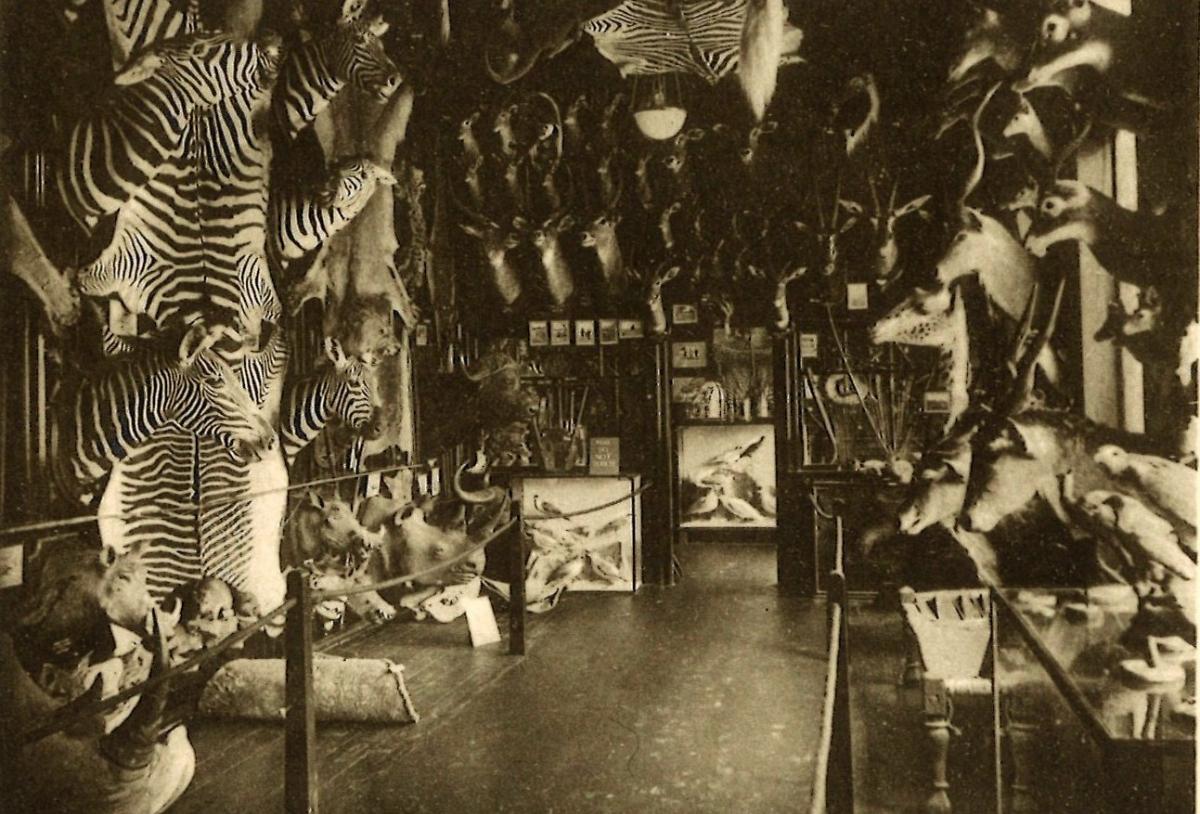

ONE hundred years ago this week, Darlington was given one of the most remarkable gifts in its history: a big game collection, the finest in the north of England, including 182 heads of exotic animals and an enormous stuffed creature that was to become a feature of many Darlingtonians’ childhoods.

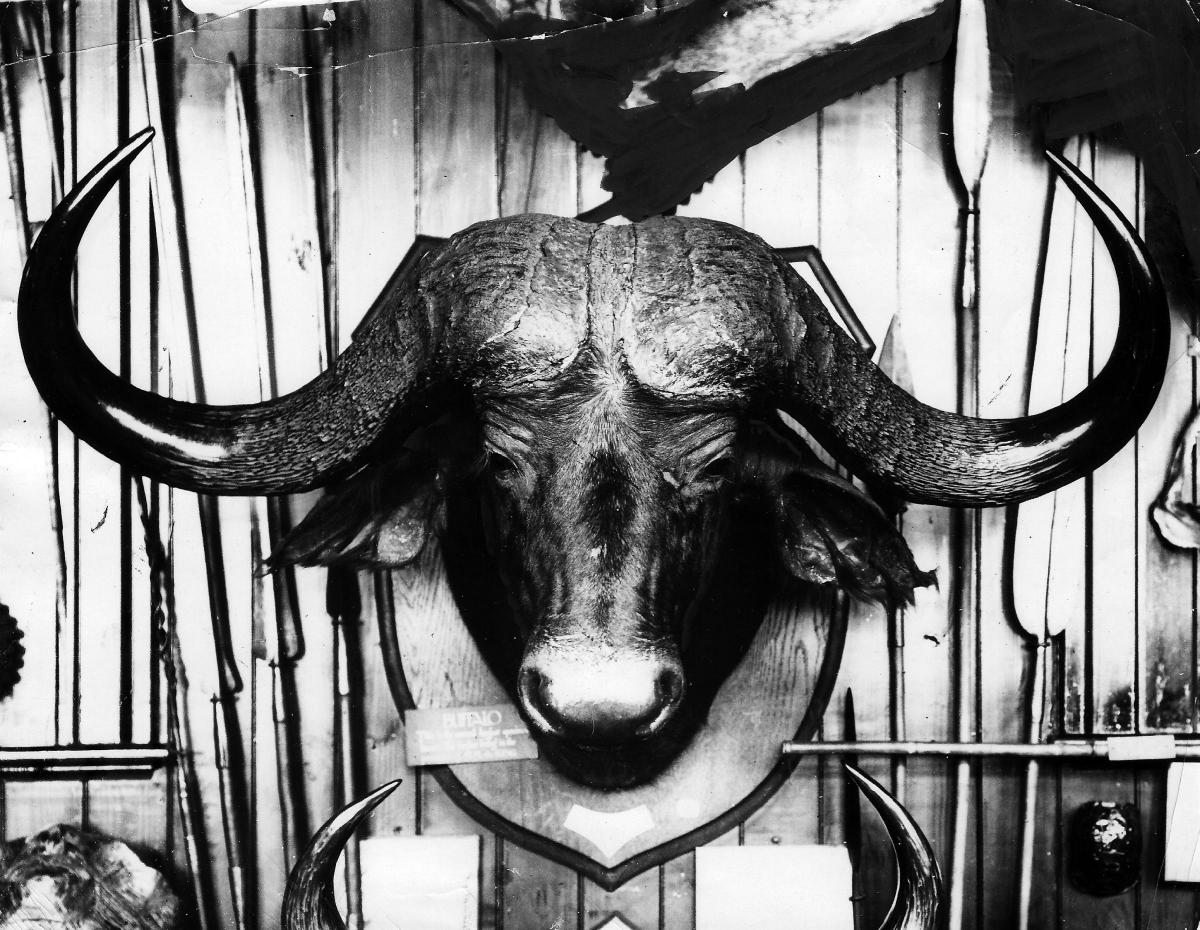

The Northern Echo in 1921 said the collection comprised “a magnificent Polar bear, the head and hide of a royal black-maned lion, the head and skull of a huge white rhinoceros, and a gigantic buffalo – second largest of its kind in the country – topi, tiang, oryx-bisa, gerenuk, giant and lesser elands, antelopes, hogs, gazelles, hippopotami, dinka, kondoo, cheeta, and a giraffe”.

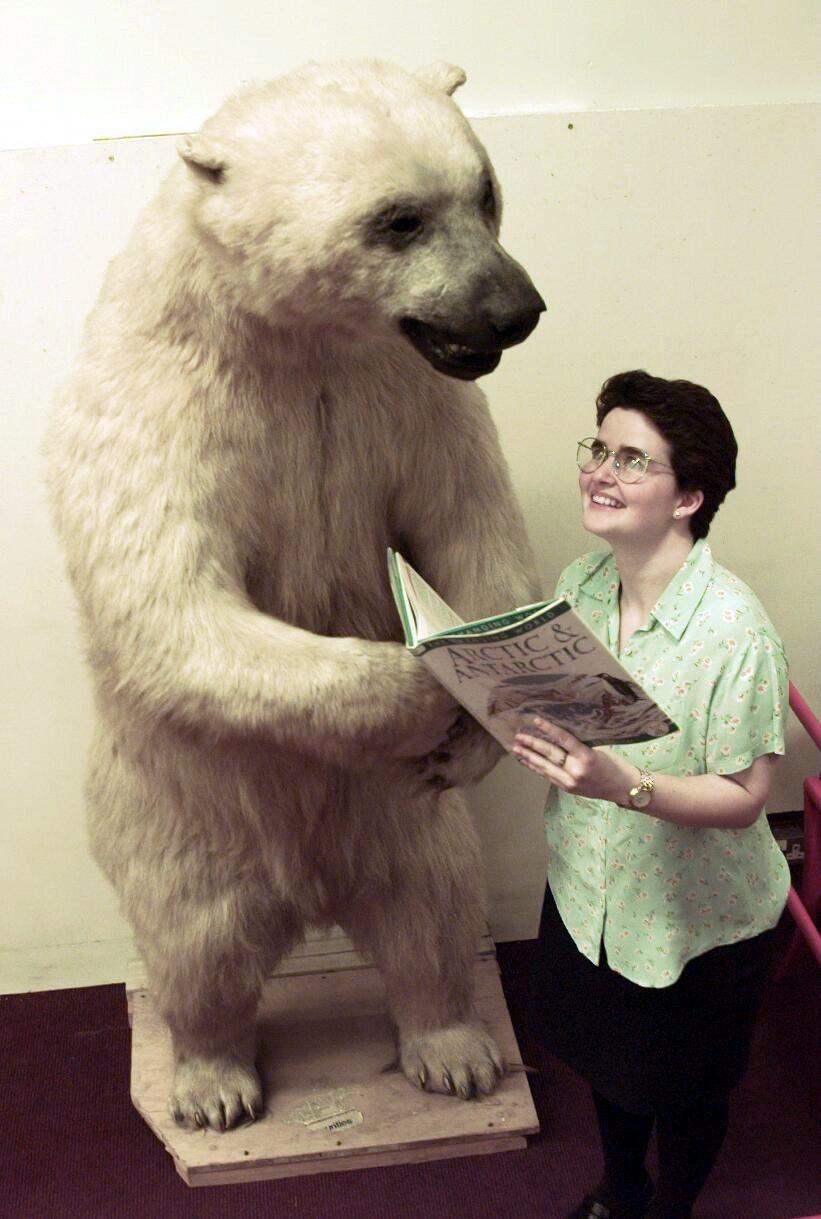

This, then, was the arrival of the 9ft tall Polar bear which seems to have started its life known as Peter the Polar. However, as the century wore on, and generations of young children rubbed its nose and poked its ribs, it became known as Fred the Bear.

The collection was a gift to Darlington’s new museum which was being put together in the former borough accountant’s offices in Tubwell Row.

The gift was from the family of the late Sydney Pearson, who had been born in Richmond and who lived in Askrigg. With his wife, referred to only as Mrs Pearson, he had suffered “great hardship and privation” travelling through British East Africa (Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania) and Sudan, blasting away at all he saw (Mrs Pearson was also reckoned to have shot some of the exhibits herself).

In the swamps of Sudan, Mr Pearson had bagged a white rhino and a giant eland (a type of antelope) which were said to be “unique specimens”.

However, also in the swamps he contracted a terrible fever which required him being carried “on a litter by natives for 140 miles across the desert”.

The litter – a portable bed – was also among the items given to Darlington.

Sadly, despite the best efforts of the natives, Mr Pearson – who had also travelled in Polar regions where he had notched the unfortunate Fred – had died from the fever.

Mrs Pearson had retired from big game hunting to live in Bellingham in Northumberland, surrounded by the trophies, but Mr Pearson’s brother lived in Darlington, where in 1917 a campaign had begun to open a town museum. The council had agreed and donations were sought to fill the museum.

All manner of curios and collections were handed over, although the Pearsons’ was undoubtedly the star of the show – and Mr Pearson’s family were probably pleased to move the collection on as no one would really want to inherit Uncle Syd’s buffalo heads and have them hanging round in the attic for ever more.

And in the days before giant high definition televisions, out of which David Attenborough leaps every weekend with close-ups of amazing animals, this sort of collection which have been many children’s introduction to the wonder of the world.

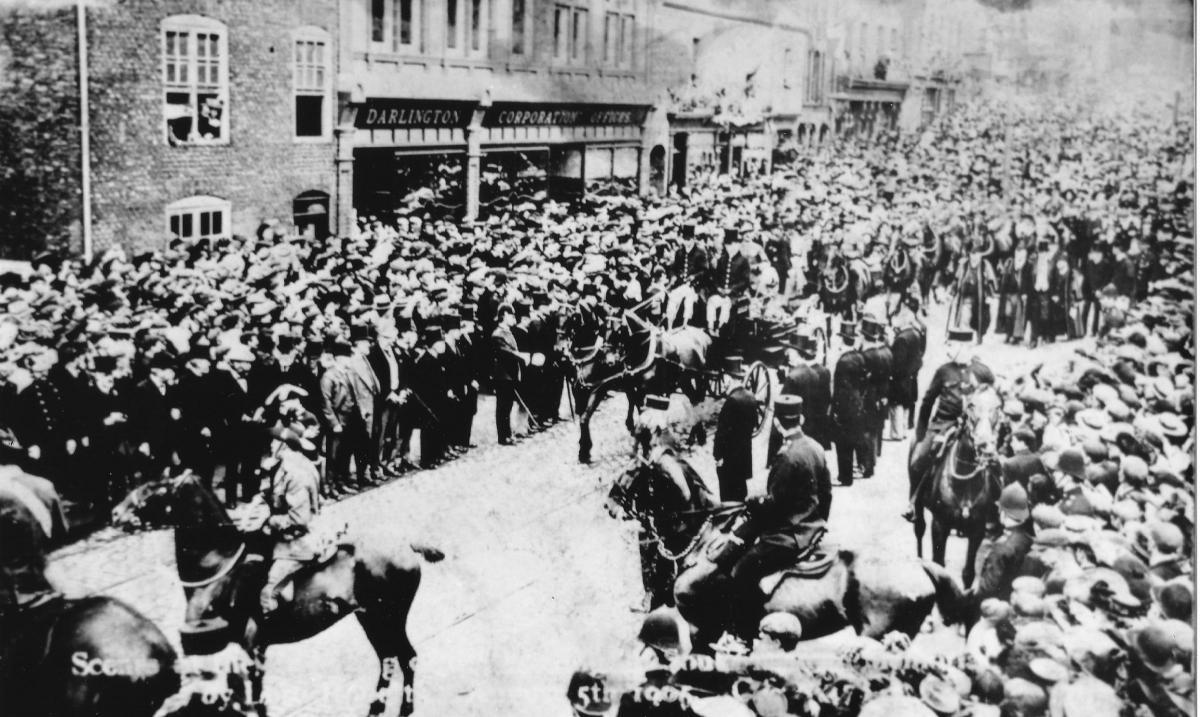

The museum opened on August 1, 1921, in the former borough accountant’s offices which had been built in the late 1890s on the site of Clapham’s ropeworks. Half of Clapham’s three storey house had been allowed to survive next to the offices, and when the museum opened, a new door to it was placed in the old house with the giant word “Museum” over it in the stonework.

Over the decades, the museum became crammed, and indeed cramped, with all sorts of curios.

It closed in 1998, when some of its contents were returned and some were dissipated to other museums across the Tees Valley, especially the railway museum in North Road.

Fred the Polar Bear went to Darlington library for a brief period before a home was found for him in the Captain Cook Birthplace Museum where he is still on display. He illustrates an entry in Capt Cook’s diary telling of eating “white bears” which, he said, had a fishy taste.

Do you remember the big game collection? Do you remember the museum? What exhibits have stayed with you? And can you tell us anything about the Pearsons? Please let us know…

FOR centuries, ropemakers had used a stretch of land beside St Cuthbert’s Church as their ropemaking walk down to the Skerne, which was lined with their ramshackle huts. One ropemaker would hold two lengths of hemp the ends of which another ropemaker would take and walk backwards down the yard twisting the twines together. Then a paste of soap, oil and gum was applied to make the rope flexible.

The last of the ropemakers was RH Clapham, who took over the ropery in 1879.

In 1895, the council replaced the Stone Bridge over the Skerne, and the ropers’ yard, including six cottages, was cleared to create the green area where the Boer War memorial was placed in 1905 – this was originally called Ropers’ Park, but it was renamed St Cuthbert’s Green in 1896.

A portion of Clapham’s three storey house survives next to the museum, and on its side you can still see where the brickwork has been chamfered on the ground floor to give carts a little more room to enter the ropery yard.

IN the papers of 150 years ago this week was a curious story about an old widower from York who had advertised in the columns of the Echo’s sister paper, the Darlington & Stockton Times, for a new wife. It was said that he had “arrived at the winter period of existence but still had inclinations to again enter the state of wedded bliss”.

Cruelly, young men of Darlington “intent on a lark”, had responded to his advert and written back saying that they were a lady with £60 annual income and “no end of charms”.

“The letters were in the delicate calligraphy of a lady,” said the D&S, “and there could be no doubt.”

After a further exchange, the old man – who could not benefit from swiping right on an online dating app – arranged to meet his new paramour at inn in Darlington.

“An afternoon train brought the luckless man, and forthwith he hastened him with all speed to the appointed trysting place,” said the D&S. “There stood the lady in propria personae and, after a sumptuous tea, the happy couple started for a walk round the town, and a jeweller’s shop was visited, where probably the wedding ring was procured.

“But, alas! for dreams of human felicity.”

Back at the inn, the lady’s brother made a noisy entrance and dragged her away from her betrothed, and then the unfortunate fellow was set upon by the conspirators.

“The poor old man had to ‘shell out’ with the best grace he could muster, and his new found acquaintances drank his health and made him the sport of their graceless witticisms,” said the paper. “Not till the next morning, we are told, did he finally rid himself of their acquaintance.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here