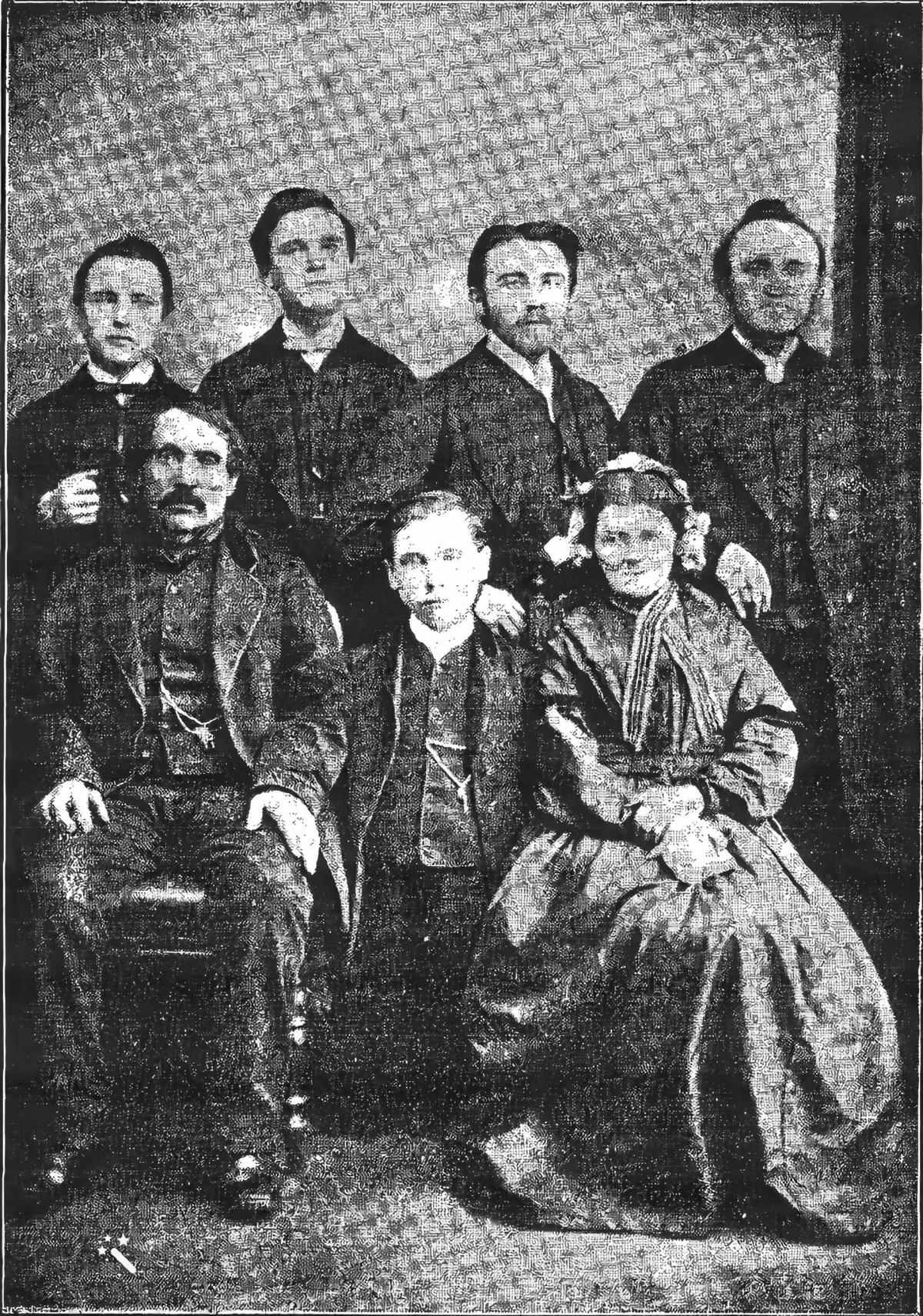

THOMAS DAVIES grew up in one of the tight two-up two-down terraced houses that sprung up in Witton Park in the middle of the 19th Century. He was squeezed in behind its front door with his five brothers and sisters and his mum and dad.

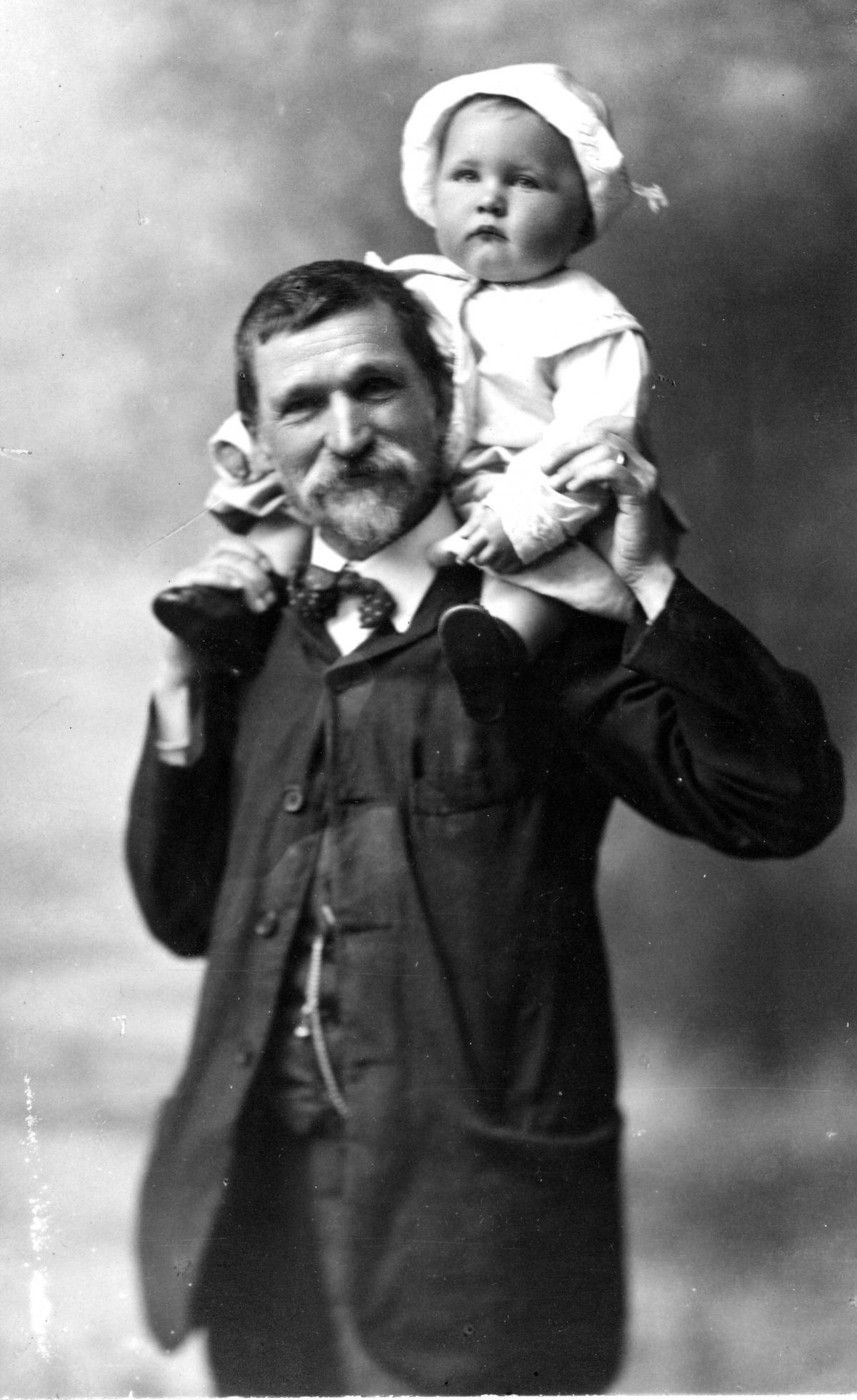

As soon as he turned 11, he followed his Welsh father – and his elder brothers – to labour in the ironworks and yet, amazingly, he ended up lecturing in Arabic and Hebrew across Europe with honorary degrees to his name from universities in Leipzig, Jena (in Germany), Geneva and Durham.

Not only did he have lots of letters at the end of his name, but in the middle of it, to differentiate himself from other people called Thomas Davies, he placed the name of the ironworking community in which he had grown up: he was Thomas Witton Davies.

His parents, Edmund and Elizabeth, moved from Nantyglo in Glamorgan in the 1850s to County Durham soon after he was born to work in the blast furnaces of Witton. They lived in 44 Low King Street – one of the demolished streets which featured on the map that appeared in the centre of Memories 507.

It was a terraced house that had just two books in it – the Bible and Pilgrim’s Progress, which was in Welsh.

However, a couple of streets away, up near the ironworks, was the Mechanics Institute, which had a library of 400 volumes. One of the books he borrowed from there was Samuel Smiles’ Self-Help, a book of great importance in Victorian times.

“When I had set down the book I felt I had no need to spend the rest of my life in the ironworks,” he wrote. “Others had risen from positions as low as mine. Why not I?”

He returned to Wales in 1872, aged 21, to enroll in a Baptist college at Haverfordwest – he had been baptised in the River Wear in 1863. Now there was no stopping him: college led to university in London, from which he returned to be a pastor in Merthyr Tydfil, and lecture in classics and Hebrew in colleges.

At one of the colleges, he discovered the principal was also called Dr Thomas Davies, said he added “Witton” to the middle of his name so his children took Witton-Davies as their surname.

As his reputation grew, he spent terms lecturing in German universities and a year at Leipzig university. He returned to become the first Professor of Hebrew at the University College of North Wales.

“His students at Bangor held him in very high regard, in no way diminished by his many eccentricities,” says one biography, which suggests he was extremely eccentric.

When he died in 1923 he had amassed an amazing library of books – some sources say 8,000, others 17,000. Either way, it was a far cry from the two books he grew up with in the home of his “industrious and frugal” parents in the terraces of Witton Park.

MARJORIE LAMBARD’S father, Charlie Hewitson, ran a shop in Witton Park and was a Methodist preacher. He told Marjorie an amazing story about the scholar Thomas Davies’ upbringing in the ironworks village.

Marjorie says: “My grandmother, Mary Ann Hewitson nee Belton, was born at California, Witton Park on May 22, 1876, shortly after Thomas left the village.

“The story goes that the Davies family were so poor that they could not afford to buy lamp-oil, so they only burnt candles.

“The residents of the adjacent terraced house could afford to burn oil lamps which gave a much better illumination so they removed a brick on their side of the dividing wall and the Davies family removed a brick on their side of the wall and the oil lamp was placed on a shelf near the aperture so that the light shone through.

“Thomas was able to study with the borrowed light!”

Marjorie finishes: “His achievements brought pride to the village and his memory lives on, as illustrated by your article.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel