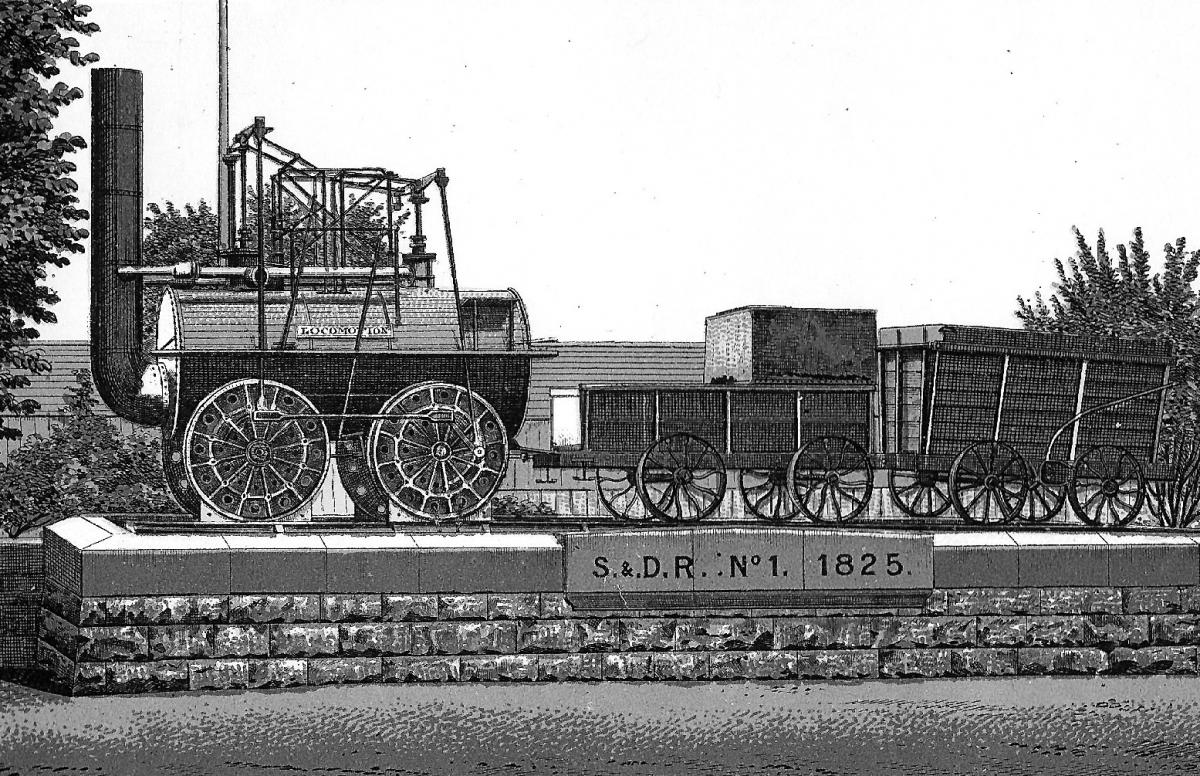

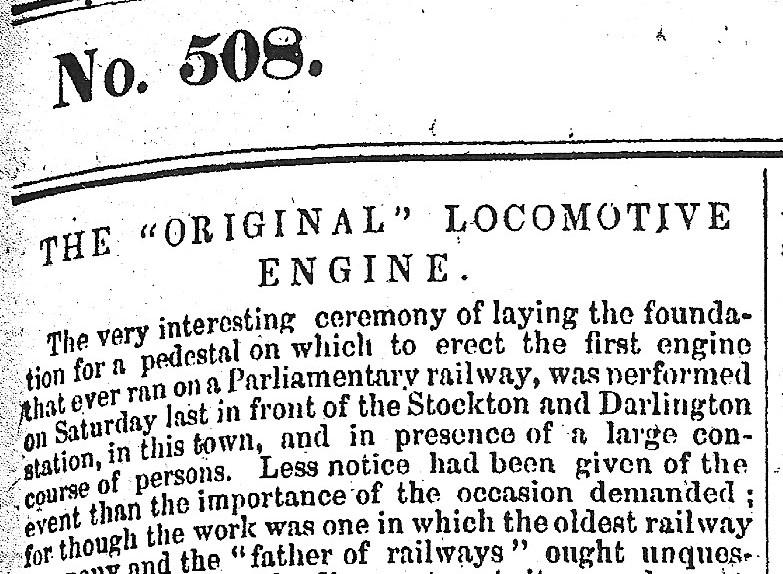

FLAGS flew, bands played, people cheered and Locomotion No 1, saved from the scrapyard, stood quietly by as Joseph Pease laid the foundation stone of the pedestal on which the historic engine was to be placed.

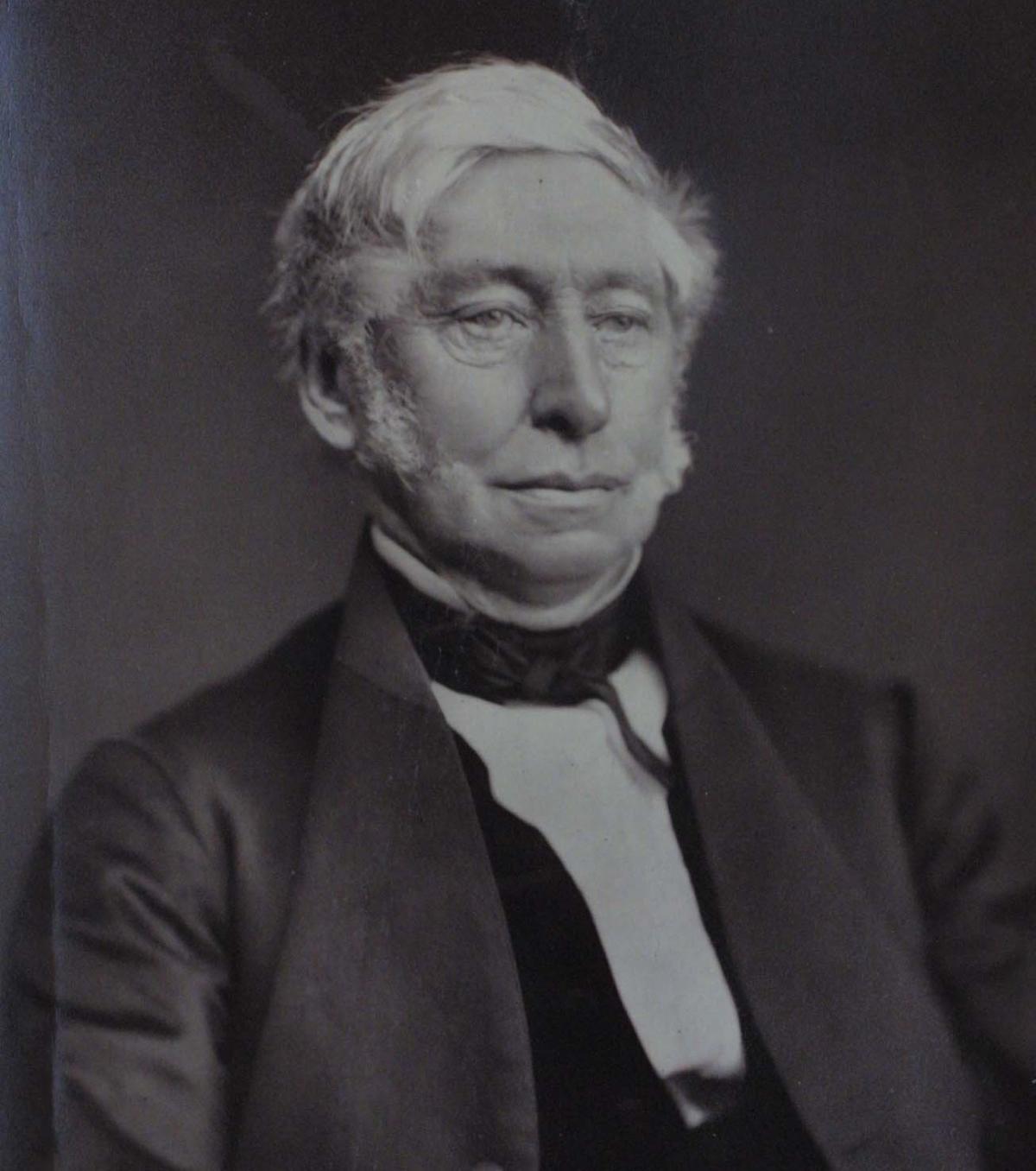

As the first part of the day-long proceedings on June 6, 1857, came to an end, Henry Pease, Joseph’s younger brother who was the newly elected MP for South Durham, took to the plinth and said that “he rejoiced at seeing the first locomotive about to be placed in a suitable position, so as to hand down to posterity a memorial of one of the greatest events the civilised world ever witnessed”.

That day marked the start of 163 years in which the engine has been on display in Darlington, but those 163 years are now likely to come to an end in early March when the engine’s owner, the National Railway Museum, remove Locomotion No 1 from the town.

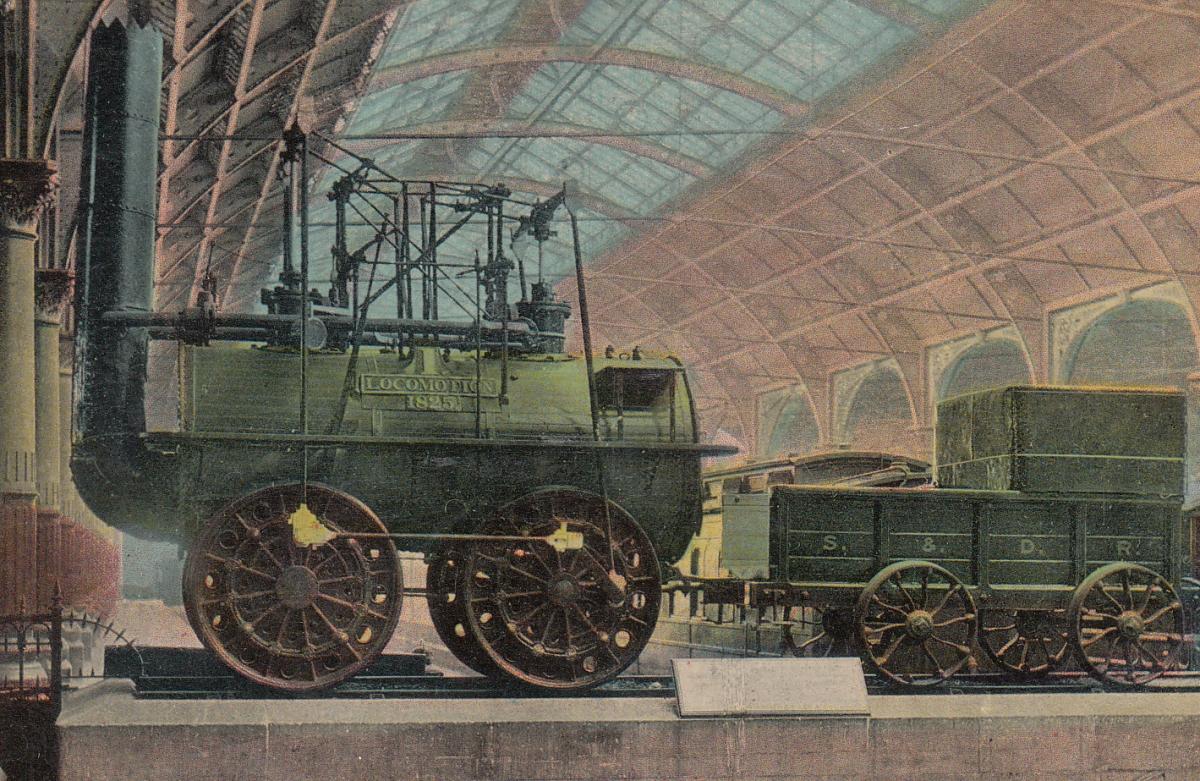

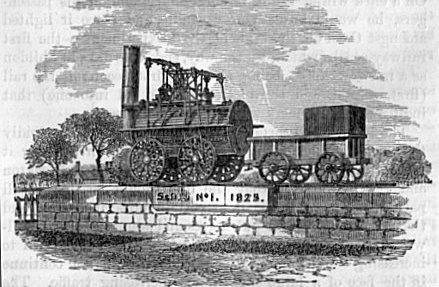

Locomotion No 1, built in Newcastle, had opened the Stockton & Darlington Railway on September 27, 1825, pulling the first train from Shildon to Stockton. A rudimentary iron horse, it had quickly been superseded by advances in technology and so in 1846, it had been pensioned off to Peases West colliery at Crook.

On January 16, 1856, it had been listed for sale as surplus to requirements. Joseph had spotted it, removed it from sale, and spent £50 restoring it ready for it to be placed “in a suitable position” outside North Road Station, near where it had rested during its inaugural journey.

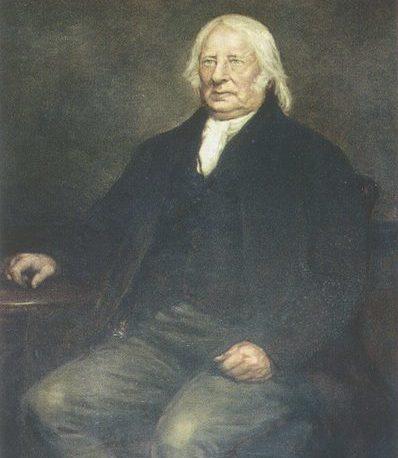

He had hoped his father, Edward, would have laid the foundation stone, but, having just turned 90, Edward declined to attend and sent a letter offering his apologies.

With “flags flying on all hands and the sun shining so brightly upon the scene as almost to scorch every person and thing exposed to its rays”, his letter was read to the crowd.

“When I first moved the introduction of the railways,” he said, laying claim to his position as the Father of the Railways, “with two or three helpers, and such an engineer as the late celebrated George Stephenson (then first drawn from obscurity), their success and importance have far, very far, exceeded the most favourable anticipations.”

He said that for four years before the railway had opened, they had done “our then unpopular work, opposed by magistrates, commissioners of turnpikes etc to the full of their power.

“Steady, disinterested attention, without one shilling of fee or reward, brought our work, thankless and wageless, to its completion.

“And it is with inexpressible satisfaction I contemplate that so large a portion of the civilised world is now reaping inestimable benefits from this mode of transit.

“When I see the hundreds of poor Irish reapers so quickly and easily transferred from country to country, and our beloved Queen with so much ease, rapidity and comfort, conveyed from Windsor to balmoral, the sight and reflection delight me.”

Everyone applauded.

His eldest son, Joseph, then spoke, remembering how on opening day “an aged farmer at Fighting Cocks, seeing his hand placed on the side bar (of Locomotion No 1), wanted to know if they pulled her ‘by them things’, taking for granted that it was a mere piece of mechanism without the agency of all-powerful steam”.

The Darlington & Stockton Times – the older sister paper of The Northern Echo – reported that Joseph placed a copy of its latest edition inside the foundation stone along with “a time-bill” for that morning’s special excursion on the newly-opened Barnard Castle line to Redcar, plus “some coins and stamps, and also a box made of cannel coal by Robert Murray as a tribute of respect to Mr Edward Pease.

“Several pieces of cannon were fired when the stone had been lowered, and cheers (faint for want of a fugleman) were given by the company standing around.”

Then Henry Pease had his turn to speak. He’d been 18 on opening day, and remembered how “No 1 engine sent forth such a black cloud that the generally expressed opinion was ‘I’se warn she gans wi’smyuk’.”

He contrasted that inaugural journey with that morning’s journey when from Barney, 700 people “had been conveyed to enjoy the delightful breezes of the sea shore”.

Locomotion No 1, he said, was “the pioneer of the steam engine of the present day”, and it had ushered in an era in which “hundreds of thousands of men who by industry and talent had been enabled to gain an honest, comfortable and in some instances even a luxurious living”.

Then John Dixon, the eminent engineer who hailed from Cockfield, spoke. He remembered walking the line a week before opening day with George Stephenson, who had been in such great spirits that when they dined at the Vane Arms in Stockton, George had “stood treat of a bottle of wine, a thing by no means customary with him in those days (laughter)”.

He recalled how Mr Stephenson had said “he looked forward to this railway producing effects very unexpected, and, addressing his son, Robert, and me said: ‘Ye lads, I expect, or I hope, may live to see the mail coaches taken to London on railways by steam at 15 miles an hour.’.”

He finished by saying that before he died in 1848, Mr Stephenson himself had travelled many times at twice that speed.

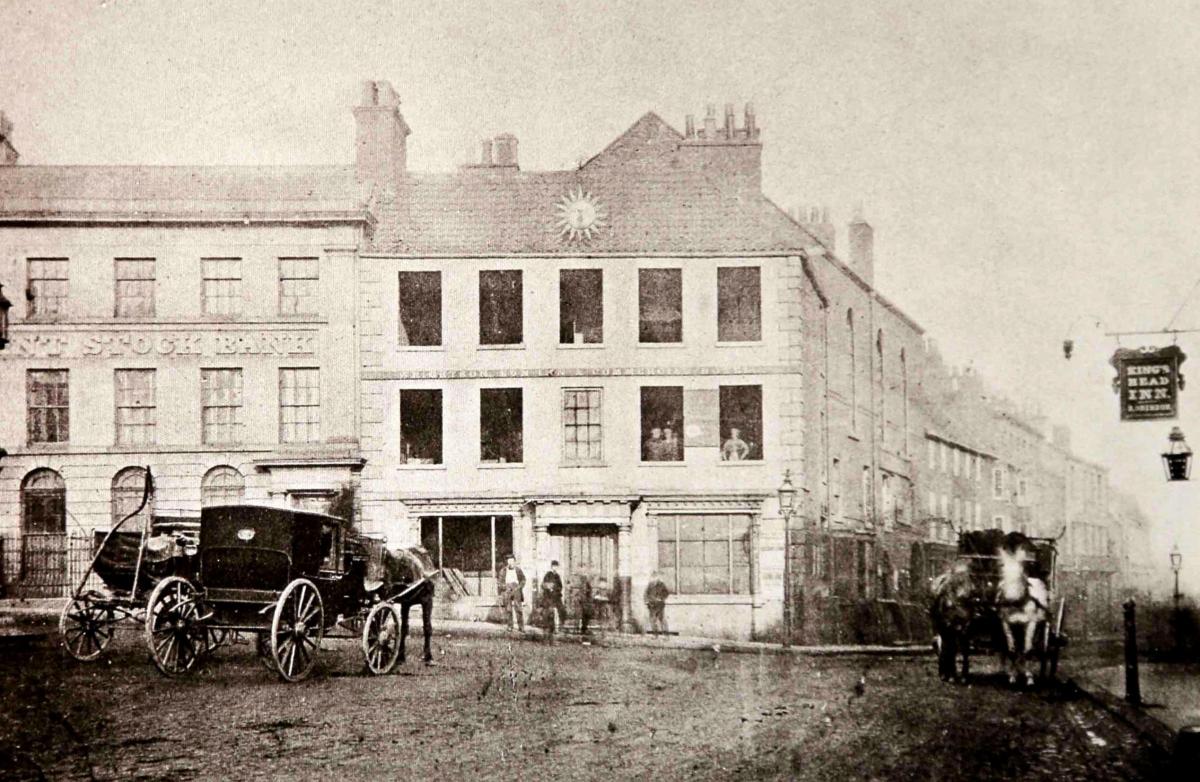

And so, on a wave of wonder and nostalgia, the railwaymen left Locomotion No 1 at the station and processed behind Hoggett’s brass band in to the town centre to the King’s Head Hotel where landlord John Wrightson served an “excellent dinner”. That, of course, was followed by more speeches.

“Soon after five o’clock, the company adjourned to Pierremont where Mr Pease threw open his gardens and grounds and provided tea, served up in a tent,” said the D&S Times. Pierremont was “the Buckingham Palace of the North” that Henry Pease had built as his family had prospered from the fortunes made by the engines that had followed in Locomotion No 1’s wake.

And, of course, after tea, there was a third bout of speeches.

One was made by a Mr Glass, who had also been present on the opening day in 1825. He said: “The locomotive has been termed the eighth wonder of the world, but compared with this wonder, the other seven sink into comparative insignificance.”

On opening day, he said Locomotion No 1 had hauled a train of 32 wagons, but that very week, he had seen a train of 154 wagons, and he shouted out: “Hail wonder-working steam!”

The D&S concludes its report of events by saying: “Tea was followed by cricket, quoits etc, and so the evening passed over most agreeably.”

Locomotion No 1 was on its pedestal and all was right with the railway world – but, after 163 years, for how much longer?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel