IN its 950 years, Richmond castle has seen many curious goings-on, but perhaps none has been more curious than the carryings-on between its founder and the daughter of King Harold.

Gunhilda, the most beautiful woman in the kingdom, was holed up in a nunnery, going blind, when she fell in love with Count Alan, the creator of the castle and the most powerful man in the north. She left her nunnery for him, and co-habitated with him for perhaps 20 years, and then when he died, she moved onto his brother, who was also called Alan.

“I believe that Gunhilda was perhaps not only a beautiful orphan princess in danger, but she was also very resourceful, playing her hand exceptionally well,” says Colin Grant, of Richmond Civic Society, in response to our article a fortnight ago about the history of the castle and the events which will celebrate its anniversary when the pandemic lifts.

“I hope that during the many exciting activities and fun planned for later in the year, Gunhilda can be elevated from the sidelines of history and can receive some recognition, alongside Count Alan, in the 950th celebrations.”

Gunhilda’s father was Harold who, of course, was the last Anglo-Saxon king of England. He was shot in the eye at the Battle of Hastings in 1066, and his defeat allowed the Duke of Normandy, who was known as William the Bastard, to become William the Conqueror.

Before William could fully have claimed to have conquered England, he needed proof that Harold was dead, and so one of Harold’s mistresses was called in to identify the body. This mistress is believed to have been Edith Swanneck – also known as Edgiva the Fair – who was not only the country’s most beautiful woman but also its wealthiest, as she owned much of East Anglia.

Edith is said to have identified Harold’s body by a “private mark” – perhaps a tattoo over his heart that read “Edith and England”.

It was a good thing the tattoo was over his heart as there was not much else left of him, poor fellow: he’d lost an arm, half a leg, had one eye gouged out and the other had a dirty great arrow protruding from it.

Edith and Harold had at least five children, one of whom was Gunhilda.

“After the turmoil of 1066, her mother sent Gunhilda to Wilton Abbey, near Salisbury, for her own safety and to be schooled by the nuns,” says Colin. “Edgiva died sometime after 1066, so Gunhilda, with both her mother and father dead, was at the mercy of the Normans. A nun's habit would have been perfect to disguise her identity.”

Indeed, as the daughter of the dead Anglo-Saxon king, the Normans might have looked at Gunhilda in the way that Vladimir Putin looks at a rival politician. Gunhilda was in her late teens and had inherited her mother’s good looks, and she could become a focal point for the opposition to the invaders.

But, in the sanctuary of the nunnery, she was safe from any attempts to eliminate her, although she did begin to go blind until she was visited by St Wulfstan, the Bishop of Worcester, who was the last surviving pre-Conquest bishop.

“He thought he owed it to her father's memory to help her, so he made the sign of the cross before her eyes and her sight was restored,” says Colin.

Her mother’s estates and great wealth could not so easily be restored. William the Conqueror had seized Edith’s lands and handed it out to his favourites, including Count Alan, who had led the Breton army into battle. Alan, who had red hair and so was known as “Rufus”, was given parts of East Anglia and land between Ure and Tees in North Yorkshire, based on the village of Gilling West.

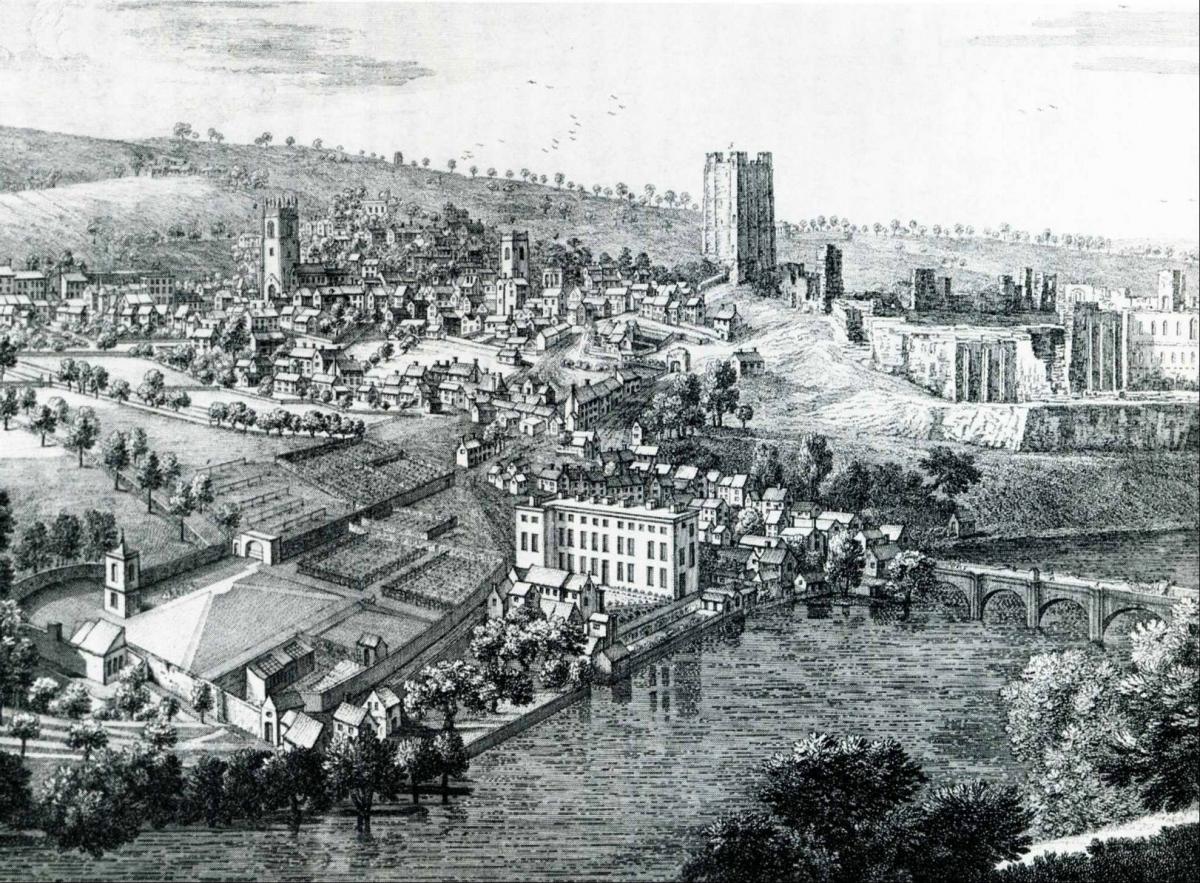

From Gilling West, Alan planned to build a huge castle on a splendid hill – a “riche mont”, in his French tongue – to show the natives how they had been conquered by a mighty power.

But if Gunhilda could somehow hook-up with Count Alan she could get her hands on what had been her mother’s.

“Gunhilda's relationship with Count Alan could have started with love at first sight on a visit to the nunnery by him, or it could have been an extremely shrewd move by her,” says Colin. “The relationship not only enabled her to legitimise her claim to her mother's considerable inheritance and, by forming a liaison with a rich Norman nobleman, it also removed the Normans’ fear that she might be a threat to them.”

So Gunhilda had experienced the full gamut of emotions: her father killed, her mother dead and dispossessed, her sight in danger, her life in peril. But she turned it all around: her sight was saved by the bishop, and her safety was assured by the count, as well as her lifestyle – Alan was probably one of the wealthiest people ever to live in Britain.

To cement their relationship, a daughter, Matilda, was born in 1073, two years after Count Alan had started building his castle at Richmond.

For 20 years, Gunhilda enjoyed stability until in 1093, Alan died, aged about 53, and the castle passed to his brother, also called Alan but as he had black hair, he was known as “Niger”.

Once again, Gunhilda had to think of ways to secure her future. The Archbishop of Canterbury told her that she was a lapsed nun, that she needed to cleanse her heart and find safety once more in the arms of the Lord.

But there was a far more exciting alternative…

“Gunhilda ignored the Archbishop's advice and developed her relationship with, and sought the protection of, Alan the Black,” says Colin.

Gunhilda seems to have lived a few more years in the security of Alan the Black, but was probably dead before he died in 1098 when the castle was passed on to a third brother, Stephen, Count of Tréguier. Hers is a curious story, from a very different time, but despite being born on the defeated Anglo-Saxon side she managed to survive and indeed prosper in the Norman era as Richmond castle began its rise on its stronghold above the Swale.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here