WITTON PARK is a classic County Durham industrial village that was born in a hurry and then stubbornly refused to die – so stubborn, in fact, that it in the last couple of decades it has been reborn as a desirable countryside location in which to live.

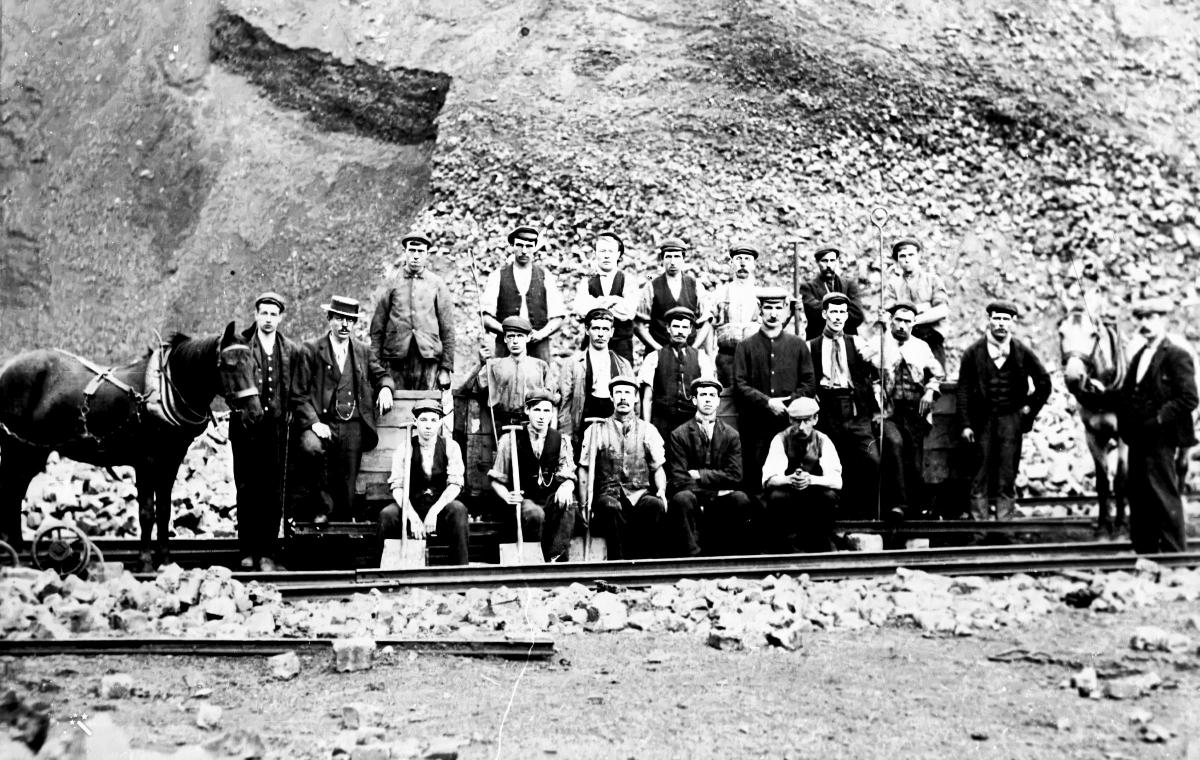

Because it was born in a hurry, when Bolckow & Vaughan established blast furnaces at Paradise Cottage there in 1846 beside the new Bishop Auckland to Crook railway, it exploded as a boomtown. Whereas America had its goldrush, south Durham had its ironrush.

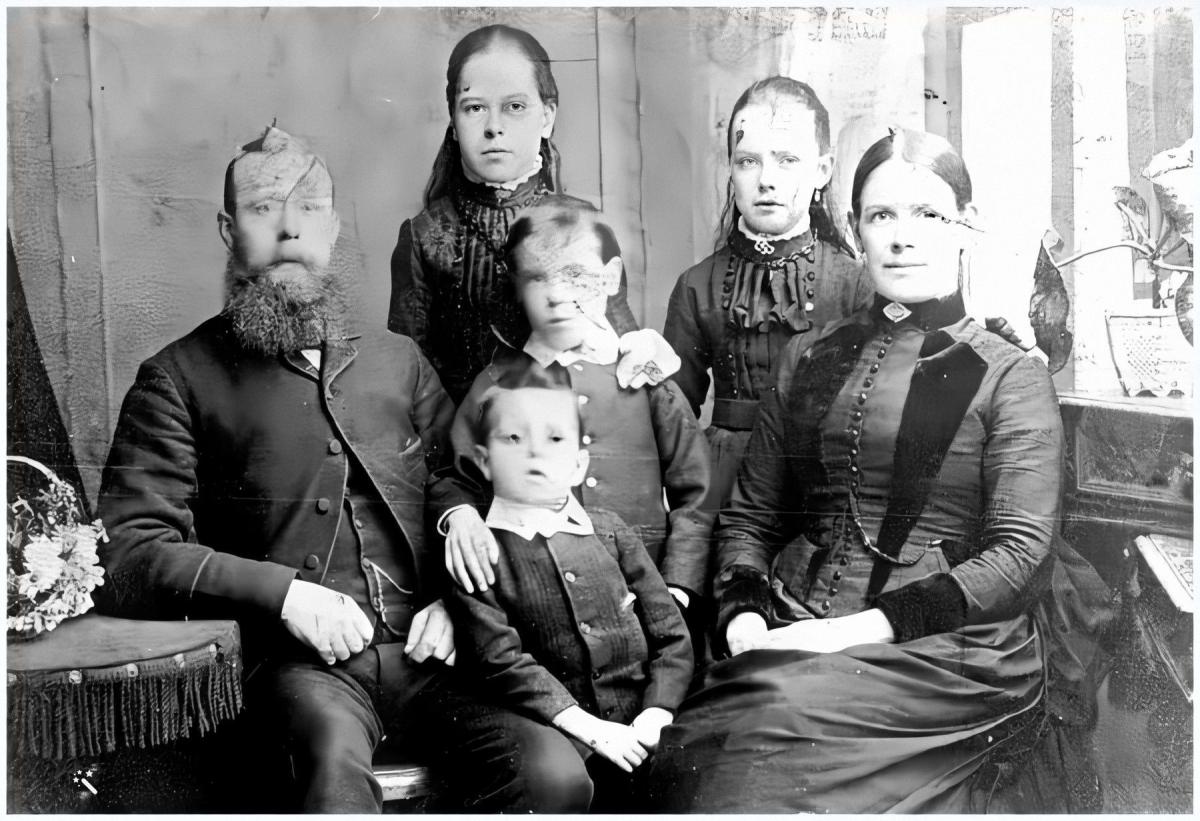

Within three years, 1,200 men were employed in the ironworks. They were nearly all incomers, from places like Wales and Ireland, and they lived with their families in hastily constructed terraced houses.

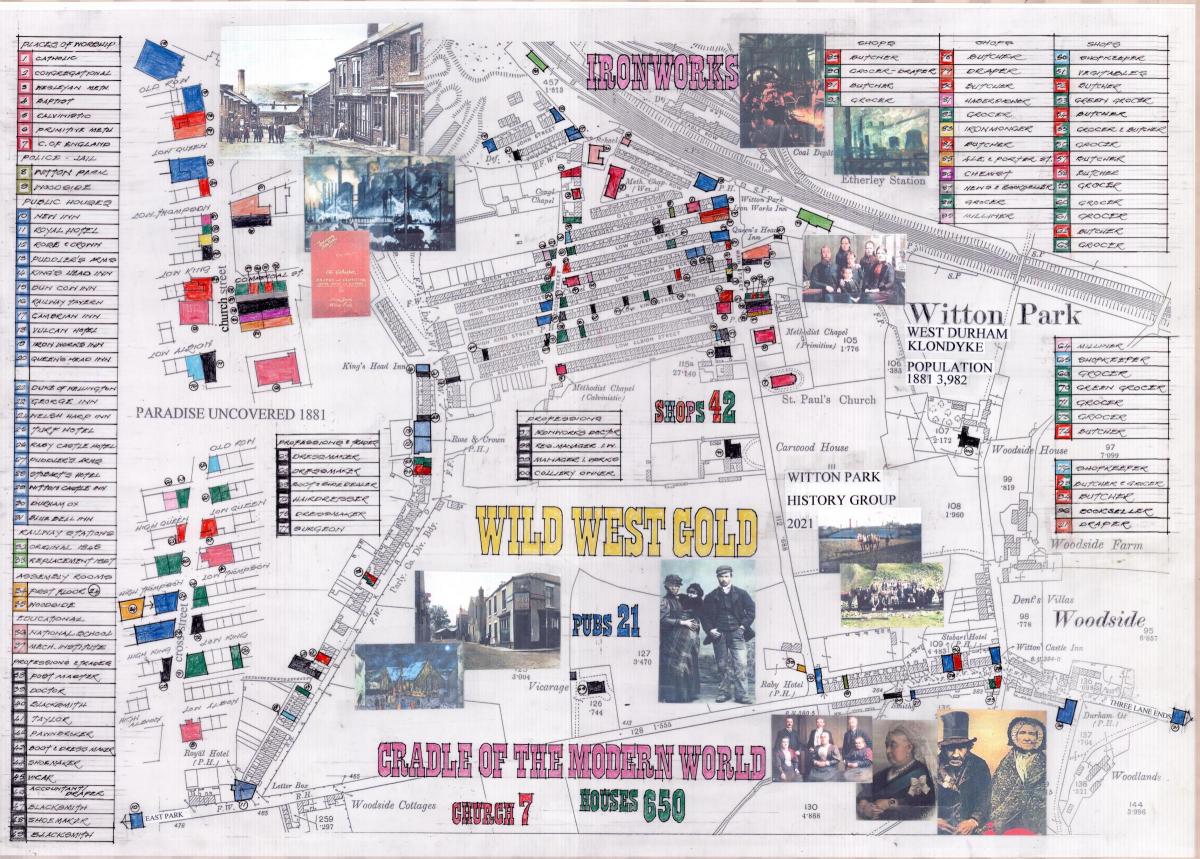

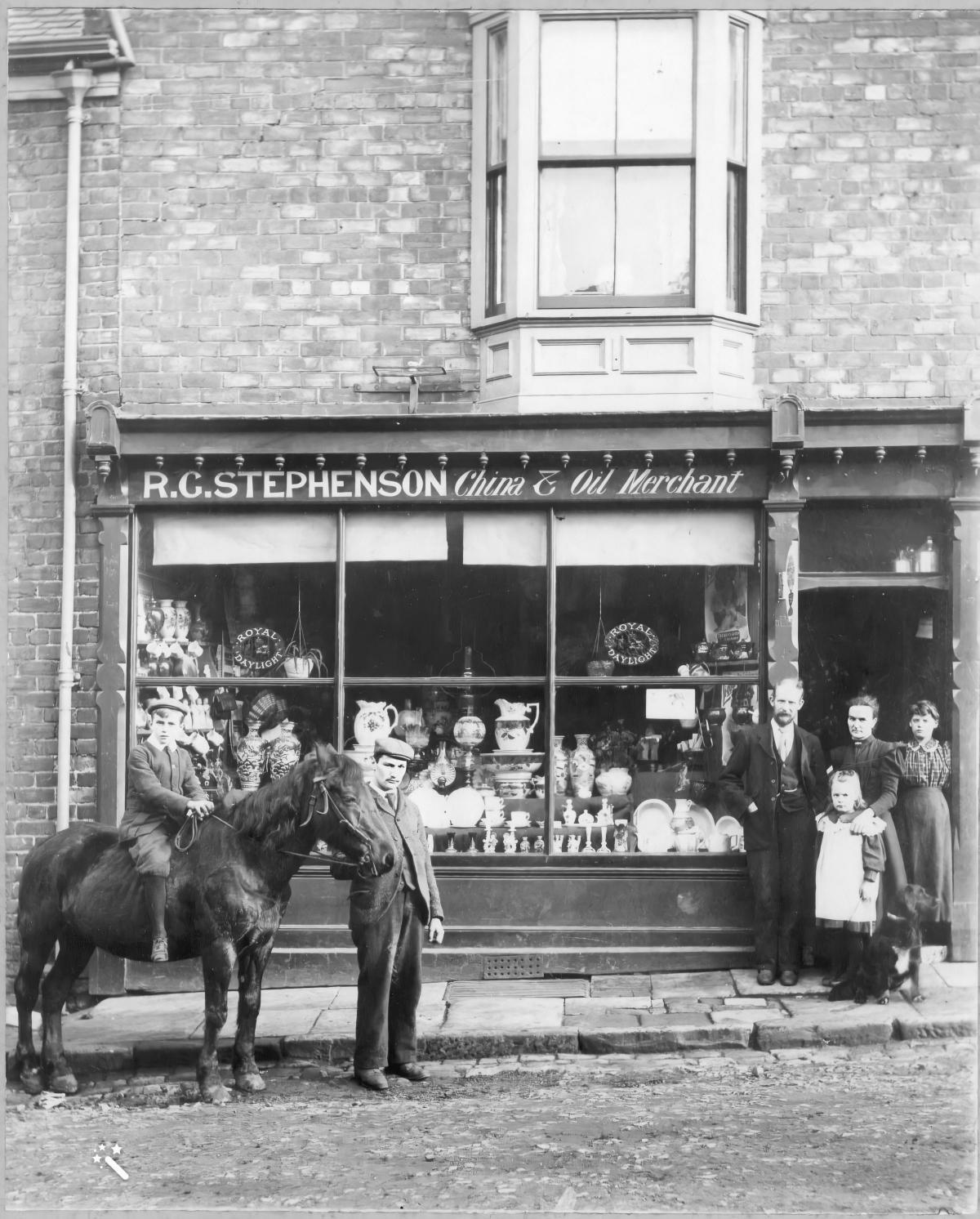

The village peaked in time for the 1881 census, upon which today’s amazing centre spread is based. The population of this Durham Klondyke was 3,982. They lived in 650 houses and they were served by 42 shops, 21 pubs, seven official places of worship (although there were perhaps 15 places where people of smaller denominations gathered), two stations, two police bases, a school, a doctor, an institute…

Among the 42 shops there were two drapers, two milliners, two booksellers and newsagents, and a chemist and a haberdasher. And there were 13 grocers, 11 butchers and two butcher-grocers and one draper-grocer.

And there were services: two blacksmiths, two shoemakers, a pawnbroker and even an accountant, although he doubled as another draper to make his figures add up.

All of these stats have been lovingly compiled onto an A2-sized map, which can be seen over the page, by local history enthusiasts Dale Daniel and Keith Belton.

They are classic Witton Parkers: the Beltons came up from Brighton in 1860 and the first of the Daniels arrived from Llantrisant in South Wales in 1871.

Their map allows you to imagine what life was like back then. With the sprawl of the ironworks supported by great limbs of railway lines at the top, you can see how life was dangerous with a hazard round every street corner.

There were accidents, there were riots. In times of strife in this frontierland, the men divided almost into tribes depending on their backgrounds: Welsh or Irish, Fenian or Orangeman.

Social conditions were harsh. There was an average of 6.1 people cramped into each of the poor quality terraced houses where every night there were tin baths in front of the fires.

But, equally, there were good times: in the 1850s, the men of the boomtown earned five times the national average.

And so there were pubs, 42 of them, their names reflecting the nature of the men who drank in them. The Puddler’s Arms, the Vulcan Hotel and the Iron Works Inn reflected the local industry; the Welsh Harp Inn and Cambrian Inn (presumably named after the mountains in Wales) spoke of where the drinkers hailed from.

The gutters of Witton Park were said to run with beer. And, probably, with other liquids. If they could run at all on a Saturday night with all the people lying in them.

Straight after the 1881 census was taken and our map was compiled, calamity: the ironworks closed in 1882. They were simply in the wrong place – the industry, of course, was focussing on Middlesbrough.

There was an exodus from the isolated boomtown, and those who stayed struggled to survive as the community around them decayed.

From 1951, Durham County Council tried to address the problems of its formerly industrial settlements by drawing up lists of places it felt had viable futures. These places went into the top categories and had investment pumped into them.

But Witton Park and 121 other communities were placed on the lowest list, Category D. They were to get no investment. They were to be allowed to wither until they died and everyone was forced out.

County planning officer Richard Atkinson wrote: "I don't think Witton Park can or should have a future."

In Witton, the worst terraces were demolished and many of the people were decanted to the Woodhouse Close estate in Bishop Auckland – or the “reservation” as it was known by the people who had once settled in Durham’s Klondyke.

But in a way, Category D was the making of Witton Park. Its people, fired by stubbornness and pride, decided to fight for its survival. It took many decades, but the site of the ironworks – which had become a railway tip – was cleared, cleaned and turned into a nature reserve, the first new housing was built in the 1990s, and the centre of the village landscaped with a memorial garden dedicated to its most famous sons, the First World War Bradford brothers, and featuring a sculpture by Ray Lonsdale, the artist responsible for Seaham Harbour’s iconic Tommy.

So times have changed, and the map takes us right back to the heart of Witton Park’s first, industrial wave. It is about 80cms by 60cms, colour, and if people would like a copy, it can be printed on demand and posted for £20 to cover all the costs. Email d.daniel110@btinternet.com

AROUND 8.45pm on January 13, 1945, Pilot Officer William McMullen made a split second decision in the skies above Darlington: would he jump from his burning Lancaster bomber and save his own life but allow his plane to plough into the houses below, or would he stay with it in its dying moments and try and steer it to the safety of farmland, even if that inevitably meant sacrificing his own life. He chose the latter course, and at 8.49pm he plunged to the ground beside what is now McMullen Road. He was killed instantly.

"For sheer self-sacrificing heroism, your husband's action will be remembered and honoured by the people of Darlington for years to come," the mayor of Darlington, Jimmy Blumer, wrote to McMullen's widow, Thelma, in Toronto, Canada, where she lived with their five-year-old daughter, Donna Mae.

A hundred or more people do gather every year at the time of the anniversary beside the McMullen memorial to remember, but in these Covid times that does not seem advisable, so Memories has teamed up with Darlington Historical Society to arrange a Zoom ceremony to which everyone is invited. Email echo@nne.co.uk and you must write "McMullen" in the subject field, and we'll send you the link, and all you will have to do is click on the link at the around 8.20pm on Wednesday.

Our ceremony will start at 8.30pm with Chris Lloyd telling the McMullen story, and we hope to link to air historian Geoff Hill who will have part of McMullen's propellor in his living room. The mayor, Cllr Chris McEwan, will say a few words and the MP, Peter Gibson, will lead into a minute's silence at 8.49pm.

Although the incident happened 76 years ago, it is still well within living memory. Valmai Denham, who now lives in Carlisle with her husband Brian, was nine at the time and lived with her family in The Byway. She told Memories only this week how she can remember the plane passing over head and then rushing outside to the see a ball of flames coming from the farmland on the east side of town.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel