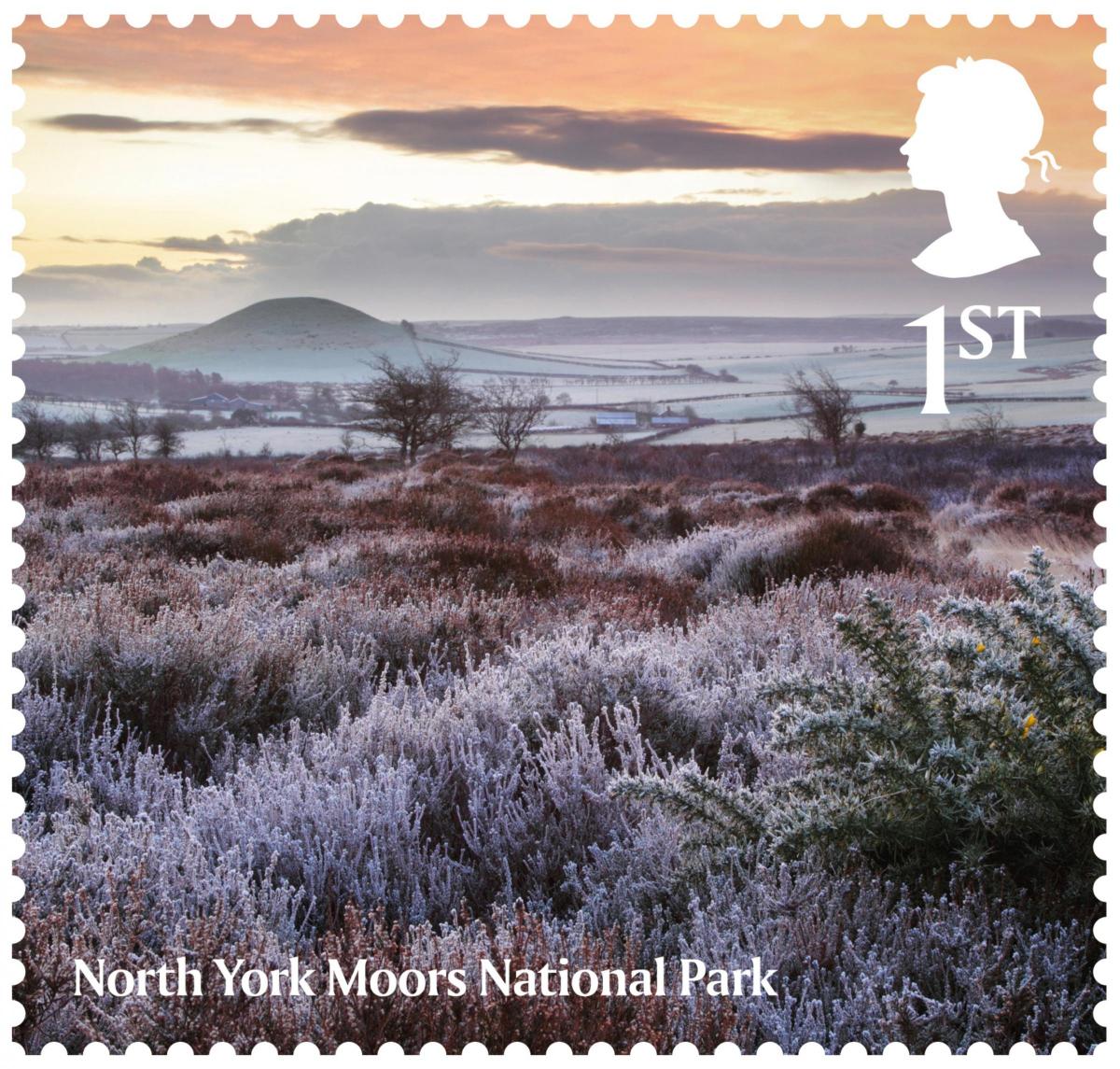

THE first postage stamps of the New Year will commemorate the 70th anniversary of the opening of the first of the UK’s 15 National Parks.

One of the set of 10, issued on January 14, carries the unmistakeable and enigmatic shape of Freebrough Hill, which is just inside the North York Moors National Park. It is beside the A171, which climbs Birk Brow bank out of Guisborough, passes the hill, before going over the moors past Scaling Reservoir to Whitby.

The hill rises about 200ft above the road and its summit is 871ft above sea level.

Freebrough was probably named by Viking invaders after the Norse goddess, Freya, who was the wife of Odin, the king of the Norse gods. Odin’s hill – “Odinsberg” – is now known as Roseberry Topping.

“As well as being in the national park, the hill is also in Redcar & Cleveland council’s Lockwood Ward, which I represent,” says Independent Councillor Steve Kay, “and I think it arouses our curiosity because its symmetrical, rounded shape makes it appear man-made.”

It is, though, entirely natural, and is referred to be geologists as an "erosional outlier".

“They conclude that the hill is a lump of hard rock, smoothed into its unnatural but distinctive shape by a glacier during the ice age,” says Steve.

However, before the geologists with their science came on the scene, various antiquarians over the centuries have made extravagant claims for Freebrough.

“For example, John Cade, who was born in Darlington in 1734, described Freebrough as “one of the greatest Celtic remains Britain can glory in”, praising its position “in an amphitheatre surrounded with hills” and believing it was “constructed on the same model as Silbury in Wiltshire”,” says Steve.

“Other ‘experts’ thought Freebrough was raised as a place of worship by the druids, or that it was a centre where legal disputes were settled.

“But the most extravagant claim came from the pen of John Hall Stevenson, squire of Skelton Castle where he held his notorious “demoniacks” drinking sessions in the middle of the 18th Century.

“By referring to the hill as “Freebro’s huge mount, immortal Arthur’s tomb”, Stevenson raised speculation about its origin to a new level.

“No doubt, he wanted to publicise his own locality but he may also have thought that the largest apparently man-made mound in the country must be the resting place of the greatest of all kings; a king whose legend is central to English medieval literature and chivalric codes, and which has survived to this day.”

So Stevenson spread stories that the rounded hill of Freebrough was heaped up by ancient Britons in the 5th Century over the last resting place of King Arthur and his knights of the Round Table.

“Unfortunately,” says Steve, “modern geologists have quashed that theory, explaining that it’s not even partially man-made.

“But, in defiance of science, when I walk alone on the hill, I sometimes pick out a faint voice on the wind: ‘Guinevere, Guinevere. Where art thou Guinevere? Guinevere, come home’.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel