WALKING out on Cotherstone Moor, Dave Middlemas and his long suffering wife, Alison, discovered the remains of a wrecked tank lying in a remote bog hidden from view by moorland tussocks.

It lies to the south of the Teesdale village of Cotherstone, and perhaps its nearest landmark is the Butter Stone – a natural stone where trade was carried out centuries ago in a time of plague, as Memories told earlier this year.

In the distance, appropriately perhaps, is a farm called Battle Hill.

Deeply intrigued, Dave, of Cockerton, began to investigate…

First of all, the Ministry of Defence to this day has rifle ranges at Battle Hill, and the Ordnance Survey map of the area is covered with “Danger Area” in red letters. But the OS map also shows how the “Danger Area” is criss-crossed with public footpaths, which can be closed if the range is being used.

Dave, of course, was walking when there were no shots being fired.

The tank he discovered in a bog was a Valentine Mk III, a classic Second World War tank of which about 8,000 were built by Vickers-Armstrong in Newcastle. The first Valentines were hurriedly built in 1940 after most British armour was abandoned at Dunkirk, and the Mk III was introduced in late 1941 when the dale around Barnard Castle was filling up with army training camps.

At any one time, there must have been thousands of men in the dale.

The camps were at Deerbolt, Stainton, Streatlam, Barford, Westwick and Humbleton.

Westwick, Humbleton and Stainton were infantry training corps. It is said that when Winston Churchill secretly visited Teesdale in December 1942, he stood on our favourite Whorlton suspension bridge and watched the men wade chest deep through the icy Tees and scale the cliffs on the Durham side, perhaps in early preparation for D-Day.

Barford, Streatlam and Deerbolt became training centres for the Royal Armoured Corps (RAC). Soldiers from Barford and Streatlam learned to drive tanks in the parkland of Streatlam Castle; those stationed at Deerbolt went up the B6277 to train in the grounds of Lartington Hall.

“One anecdote describes the extensive damage caused to the Lartington Park railings by these learners,” says Dave.

John Le Mesurier – later, of course, Sgt Wilson in Dad’s Army – trained at Deerbolt and became a captain in the Royal Tank Regiment. Norman Wisdom also served as a bandsman at an RAC camp near Barney.

Once the soldiers had mastered the rudiments of tank driving, they were allowed up onto the moorland between Bowes and Cotherstone which the War Office had taken over.

“Much of the southern half of this land, near Stoney Keld, would become RAF Bowes Moor,” says Dave. “It was an extensive storage site for airdroppable poison gas munitions, the remains of which can still be seen today together with the faded warning signs.”

Indeed, traces of low levels of Second World War toxins associated with mustard gas were present there as recently as 2008, although not in dangerous levels.

“The northern half of this area was used for a wide variety of army exercises, small arms practice and tank manoeuvres,” says Dave. “Almost in the centre of all this lies Battle Hill Farm, although its name is a pure coincidence as it predates the war by many years.”

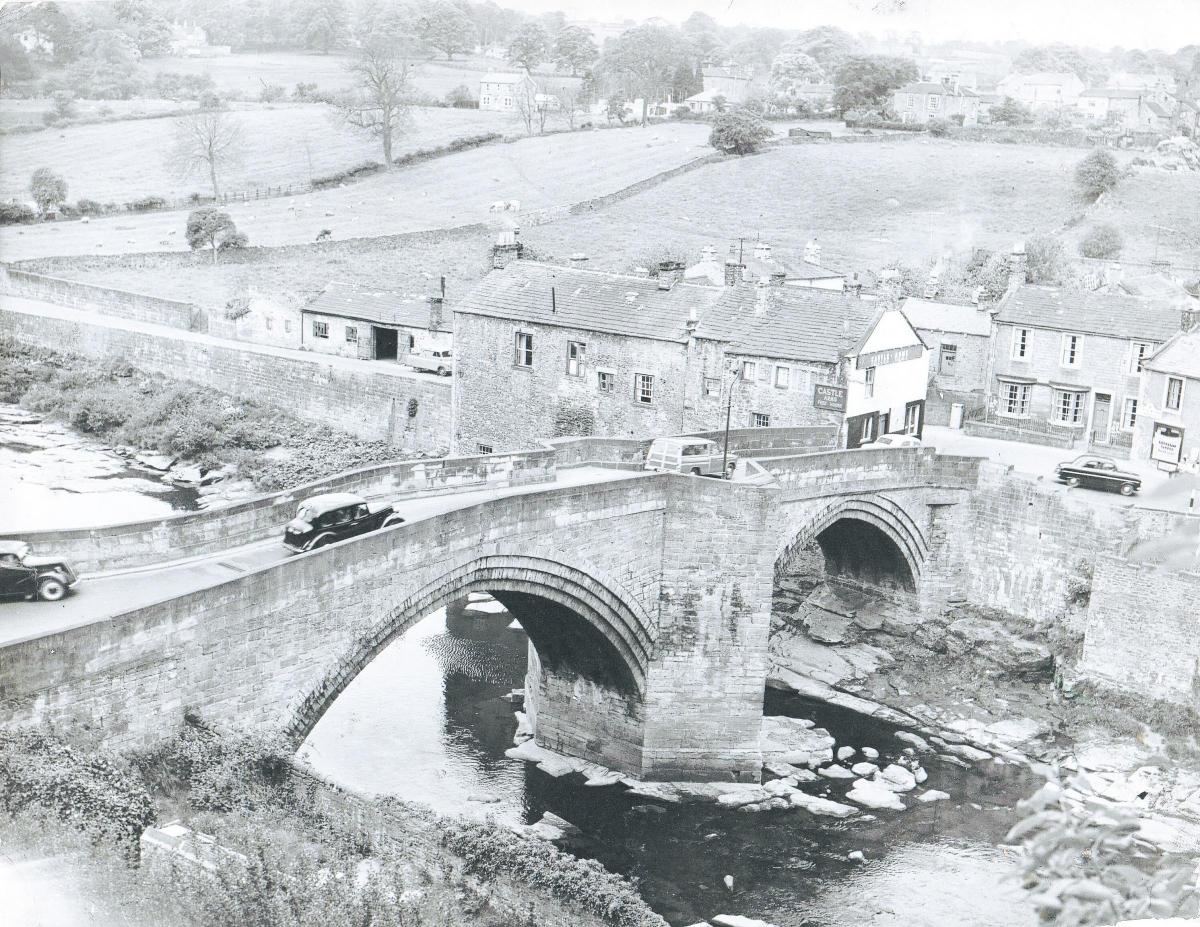

To reach the Battle Hill training ground, the tanks from Streatlam camp had to travel in troops of three through Barney, down the steep Bank and then over the County Bridge – a manoeuvre which frightened many local residents, especially if they were caught on the narrow bridge as the tanks rumbled across.

“The tanks’ metal tracks would damage the roads and the deck of the bridge was bedded with extra concrete for protection,” says Dave. “Later developments saw the addition of rubber track inserts but the bridge would still be heavily strained by a troop of three tanks crossing in close order – a combined weight of over 105 tons by the time of the 1945 models.

“At least one tank did not quite make the bend onto Bridgegate and ripped off the front of the Blue Bell pub in passing – ironically, it was a favourite haunt for off-duty troopers!”

He continues: “Quite what went on during the moorland tank exercises is rather unclear. Despite various references to small arms firing, use of mortars and other pyrotechnics by infantry well into the late 1950s, it seems live firing by tanks was only performed at the Warcop ranges just across Stainmore.”

The neighbouring farm to Battle Hill was Loups’s Hill – a strange name which apparently comes about because the beck there is narrow enough for a man to leap it. Loups’s Hill had been farmed for at least 300 years and a nearby quarry may even have produced stone in Roman times, but the soldiers took potshots at the old farm buildings, which remain ruined to this day.

The moor was also used for ground-air exercises involving planes from RAF Catterick. On February 10, 1943, Flying Officer Harry Wright, 29, from Derbyshire, died when his Tomahawk crashed on Stainmore apparently after an exercise centred on Battle Hill.

“Tank crews also trained with pistol and Sten guns for 'dismount' procedures at Cat Castle Quarry, near Lartington,” says Dave. “This was in case they had to abandon their tanks due to damage or breakdown during combat.

“Thousands of black-bereted Royal Armoured Corps troopers trained on the moor before deploying to North Africa, mainland Europe or sometimes Asia, but training was scaled down after 1945.”

Throughout the 1950s, the Teesdale camps still played host to a variety of armoured, infantry and artillery regiments, and in 1954, there is a Parliamentary report of a number of soldiers being badly injured at Battle Hill when they were recovering missiles.

With the end of the national service in the 1960s, the camps were phased out. Stainton, on the road between Barney and Staindrop, was the last to close when it shut in 1972. Its married quarters were converted into the Stainton Grove housing estate.

“All of which leaves the big question: what is the story behind the Teesdale Valentine,” says Dave.

“Obviously, it has been destroyed in situ by an internal explosion which shattered the hull outwards and spread the wheels, tracks, suspension and turret ring across the site.

“The damage is not conducive to it being hit by an armour piercing shell which would usually leave only a puncture hole and which would have filled the vehicle with supersonic shards of white hot metal.

“The holes and pockmarks on the tank clearly show that it has been peppered with small arms/light cannon fire but this appears to have occurred before it was ripped apart.

“So was it just obsolete, bogged down, stranded, abandoned and shot at, and then later blown to pieces by the army when they left in a bid to make it safe?”

If you can add anything at all to the story of the Teesdale Valentine, please email chris.lloyd@nne.co.uk. We’d love to know.

L Many thanks to Dave for all of his work.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel