THE world of archaeology has been alive this week with the news that a 5,000-year-old lost artefact from the Great Pyramid has been discovered in a cigar tin in a university collection.

The fragment of cedar wood was discovered in a secret passage leading from the Queen’s Chamber in 1872 by engineer Waynman Dixon, a man with Cockfield in his blood who now rests in Great Ayton.

Waynman placed the five-inch long piece of wood in the cigar tin with two other relics, a small stone ball and a bronze hook. The ball and the hook ended up in the British Museum, but the wood was presented in the tin to Aberdeen university in the 1940s after which it was lost – until this week .

“It may be just a small fragment of wood, which is now in several pieces, but it is hugely significant given that it is one of only three items ever to be recovered from inside the Great Pyramid,” said curatorial assistant Abeer Eladany, who discovered the Egyptian artefact mistakenly lost among the university’s Asiatic collection.

But those three items are not the only Egyptian items that our man Waynman has left for history. With his brother John, he also sailed a 224 ton granite obelisk from Alexandria so that it could become a London landmark: Cleopatra’s Needle.

John and Waynman were the great-grandsons of George Dixon of Garden House, Cockfield. George, whose brother Jeremiah is famed for creating the Mason-Dixon Line in the US, dug an experimental stretch of canal on top of the fell in 1760 at the start of the drive to connect the south Durham coalfield with the sea at Stockton. This drive led to the creation of the Stockton & Darlington Railway in 1825, and the railway’s first chief engineer was another close relative, John Dixon, of Woodside in Darlington.

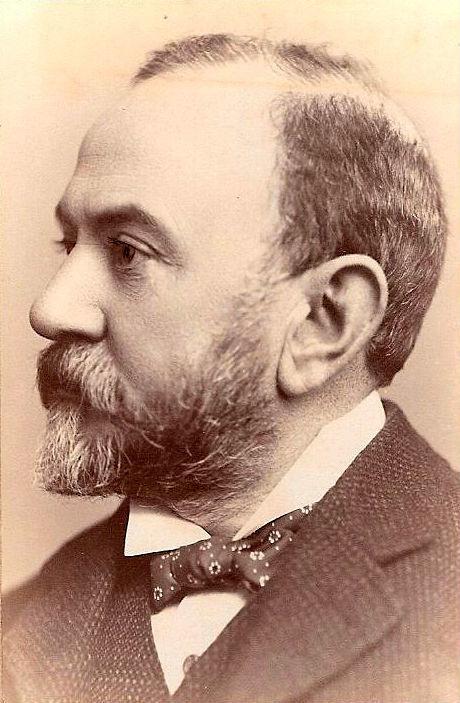

The great-grandsons – John, Waynman and another brother, Raylton – were born in Newcastle. All inherited the Dixon engineering gene.

Raylton set up the largest shipyard on the Tees, which built more than 600 ships between 1873 and 1923. He became mayor of Middlesbrough, was knighted in 1890 and was once voted the most popular man in the Boro.

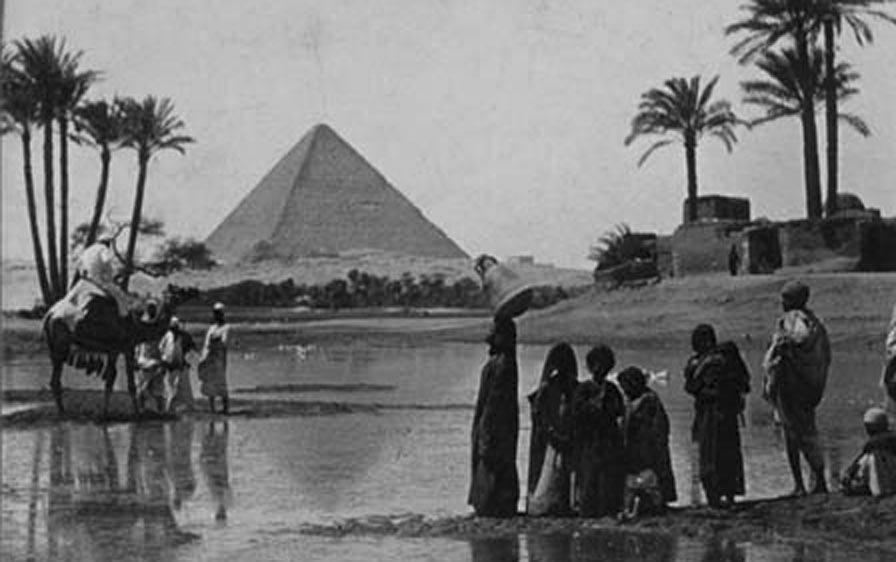

John set up a civil engineering business which, in 1871, won a contract to build a bridge over the Nile at Cairo. He went out with his 26-year-old younger brother, Waynman, and as they explored the country they noticed at Alexandria a huge stone obelisk lying in the sand.

The obelisk was one of a pair which had first been shaped in 1450BC for Pharaoh Thotmes III. About 1,400 years later, Cleopatra had the obelisks built into her Caesareum – a temple dedicated to her lover, the Roman emperor, Julius Caesar.

In 1801, when the British defeated Napoleon’s French army at the Battle of Alexandria, soldiers wanted to take the fallen obelisk home as a war memorial. The Egyptian government agreed, but the British government refused to foot the transport bill. So the obelisk remained in the sand until the Dixon brothers spotted it…

First, Waynman set to building the Cairo Bridge, Le Pont des Anglais, which was completed in November 1872.

He had, by now, fallen in love with the country – and with Selima Harris, the black, illegitimate daughter of a British diplomat. He decided to remain in Egypt and pursue his interests, both engineering and romantic.

Alexandria was extremely fashionable, and another British person out there was Charles Piazzi Smyth, the Astronomer Royal of Scotland, who was doing the first accurate survey of the 4,500-year-old Great Pyramid. He contracted Waynman and John to do some of the explorations, and in discovering the secret passage, Waynman unearthed the three relics.

He put them into a cigar tin which John brought home where the items aroused great interest – unseen for four millennia, there was speculation that they were among the tools which the ancient Egyptians had used to create their vast mathematical masterpieces.

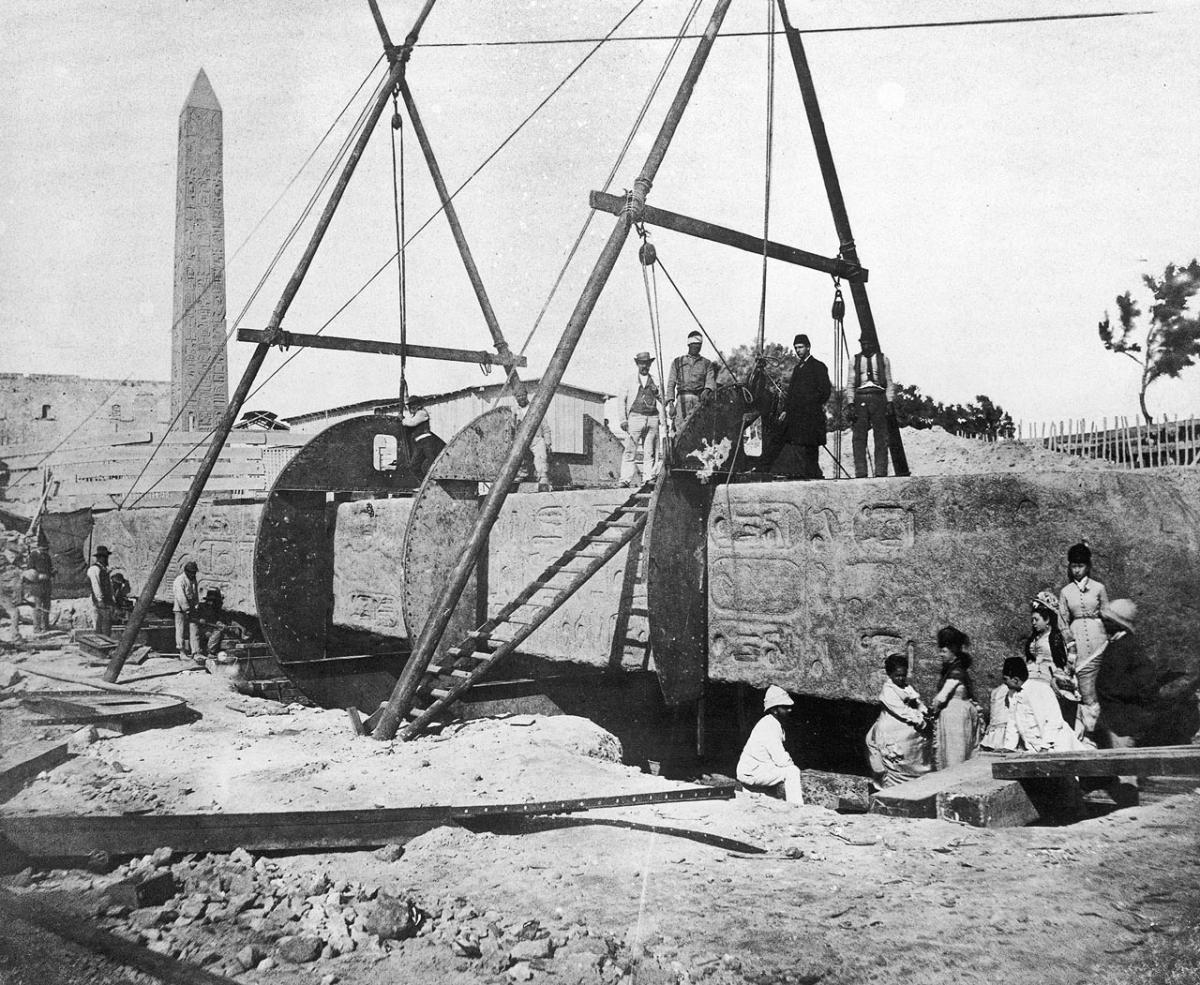

Another of Waynman’s interests was moving Cleopatra’s obelisk to Britain, but how could he transport by sea a single piece of granite that was 69ft long and weighed 224 tons?

Waynman designed a cigar-shaped iron cylinder, 93ft long and 15ft wide, which he reckoned would be buoyant even with the obelisk sealed inside it. John made the cylinder at the Thames Iron Works and sent it out in pieces to Alexandria where Waynman constructed it around the obelisk.

Waynman called the vessel Cleopatra, and he welded a cabin to it for a small crew to look after the stone on its journey. Then Cleopatra was attached by a line to a steamship called Olga and this curious convoy set sail in September 1877.

On October 14, 1877, in the Bay of Biscay, a terrible storm blew up causing Cleopatra to roll violently in the waves so that it was feared it would drag Olga down. A boat was despatched to rescue Cleopatra’s crew from the cabin, but it sank, drowning six sailors.

Olga drew alongside Cleopatra and collected the crew, and then Waynman made the difficult decision to cut Cleopatra loose in order to save Olga.

Olga made it to Falmouth and Waynman feared he had lost Cleopatra and the needle. The British public, who had donated £15,000 to fund the journey, feared they had lost their money to the bottom of the ocean.

But five days later, another steamship, Fitzmaurice, spotted Cleopatra bobbing about in the Bay – Waynman’s strange construction had remained watertight throughout. Cleopatra was reeled in and taken to the Spanish port of Ferrol.

The captain of the Fitzmaurice demanded that the Dixons pay a huge sum in salvage, but once that was sorted out, Cleopatra began the last leg of its journey, towed up the Thames with crowds cheering as it reached central London in January 1878.

One last question remained: where was the needle to be sited? The London Underground refused to allow the Dixons to erect it near the Houses of Parliament for fear that it would come crashing through into one of the tunnels, and so it had to go on The Embankment.

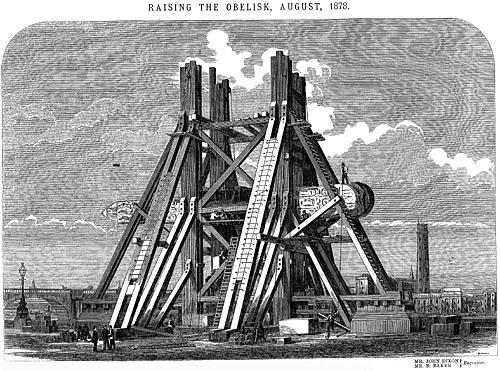

In September 1878, John built a remarkable winch to raise the obelisk, covered in Egyptian hieroglyphs, out of the cigar-shaped vessel and on to dry land.

As Cleopatra’s job was done, it was sent for scrap – but Cleopatra’s Needle still stands.

For Waynman, the completion of the monument was the end of his Egyptian adventure. Perhaps because his family did not allow him to marry Selima, he moved back to the North-East where he took charge of the Cleveland Dockyard owned by his brother, Sir Raylton. At its peak, it employed 2,300 men and as well as large steamships, it specialised in steel warships.

Waynman lived in Marton and in 1896, at the age of 52, he married Elfleda in Richmond. They had two daughters, and retired to Ayton House in Great Ayton, where he died in 1930, aged 85.

Cleopatra’s Needle in the capital city is his most visible legacy, but archaeologists are genuinely excited by the rediscovery of the fragments of wood. They have carbon dated them to somewhere between 3341BC and 3094BC, which makes them about 500 years older than the Great Pyramid which is believed to have been built in the reign of Pharaoh Khufu from 2580BC to 2560BC.

This supports the theory that the Dixon relics were used during the construction of the Great Pyramid and were not later artefacts left behind by those exploring the chambers.

Neil Curtis, head of museums and special collections at Aberdeen, said: “It is even older than we had imagined. This may be because the date relates to the age of the wood, maybe from the centre of a long-lived tree.

“Alternatively, it could be because of the rarity of trees in ancient Egypt, which meant that wood was scarce, treasured and recycled or cared for over many years.

“This discovery will certainly reignite interest in the Dixon relics and how they can shed light on the Great Pyramid.”

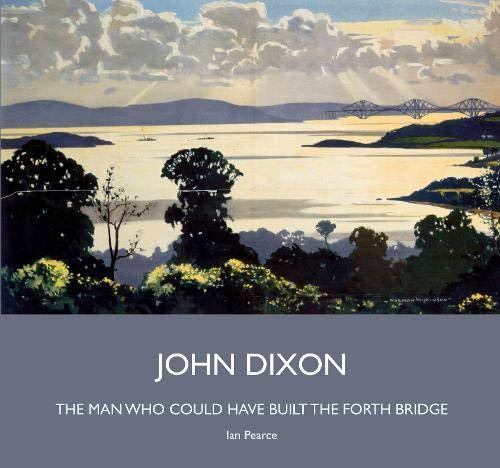

L We are hugely indebted to Ian Pearce, of Great Ayton, for his help. Much of the information and many of the pictures come from Ian’s book, John Dixon: The Man Who Could Have Built the Forth Bridge, which was published in 2019 about Waynman’s brother. The book is available on Amazon

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here