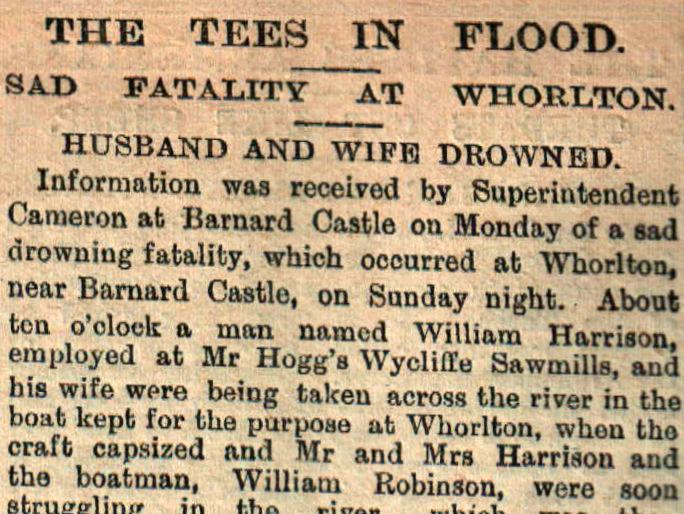

“The floods and fatalities of the River Tees form a grim chapter in the annals of Teesdale, and, from the earliest records, many a peaceful household has been plunged into deep despair by melancholy deaths all more or less attributable to the treacherous river which divides the county of York from that of Durham,” began a report in the Teesdale Mercury of September 30, 1896.

“The tragic events of Sunday night add another chapter to the dismal tale which the parish registers and newspaper files furnish regarding the calamities of the Tees, but we question whether any previous disaster is surrounded by circumstance so truly melancholy.

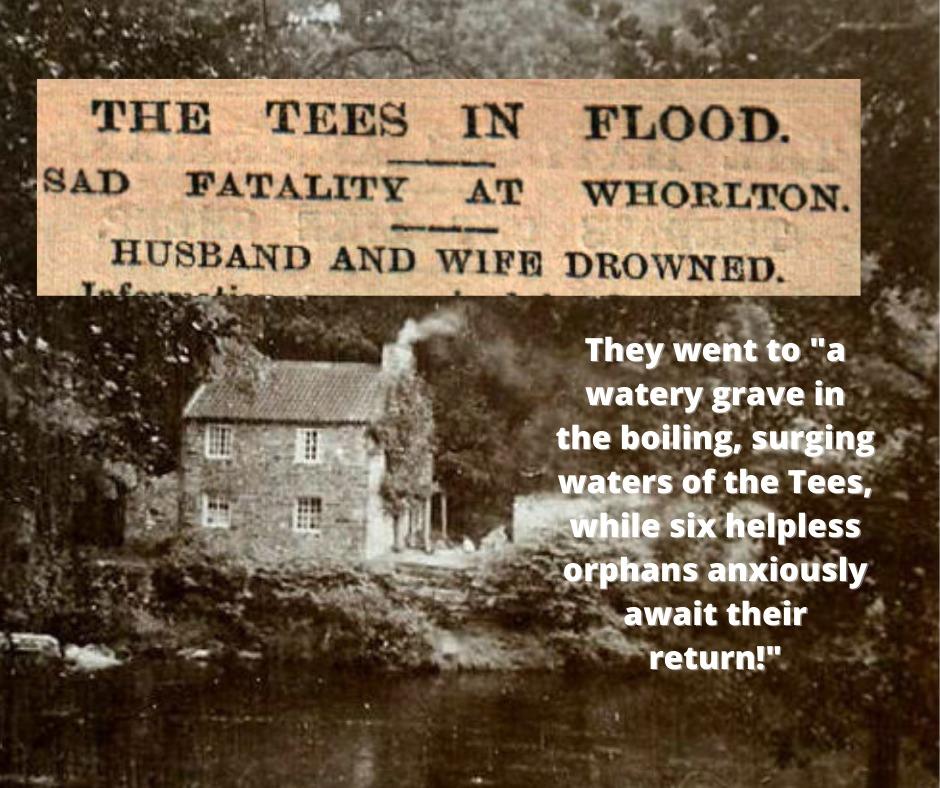

“Husband and wife, having rejoiced all day with relatives at Eppleby, are in a moment plunged into the jaws of a cruel death – late at night – and both find a watery grave in the boiling, surging waters of the Tees, while six helpless orphans anxiously await their return!

“Truly the event is without parallel in local records.”

William and Louisa Harrison, both 34, had spent a happy Sunday with Louisa’s parents in Eppleby, near Darlington, on the Yorkshire side of the river.

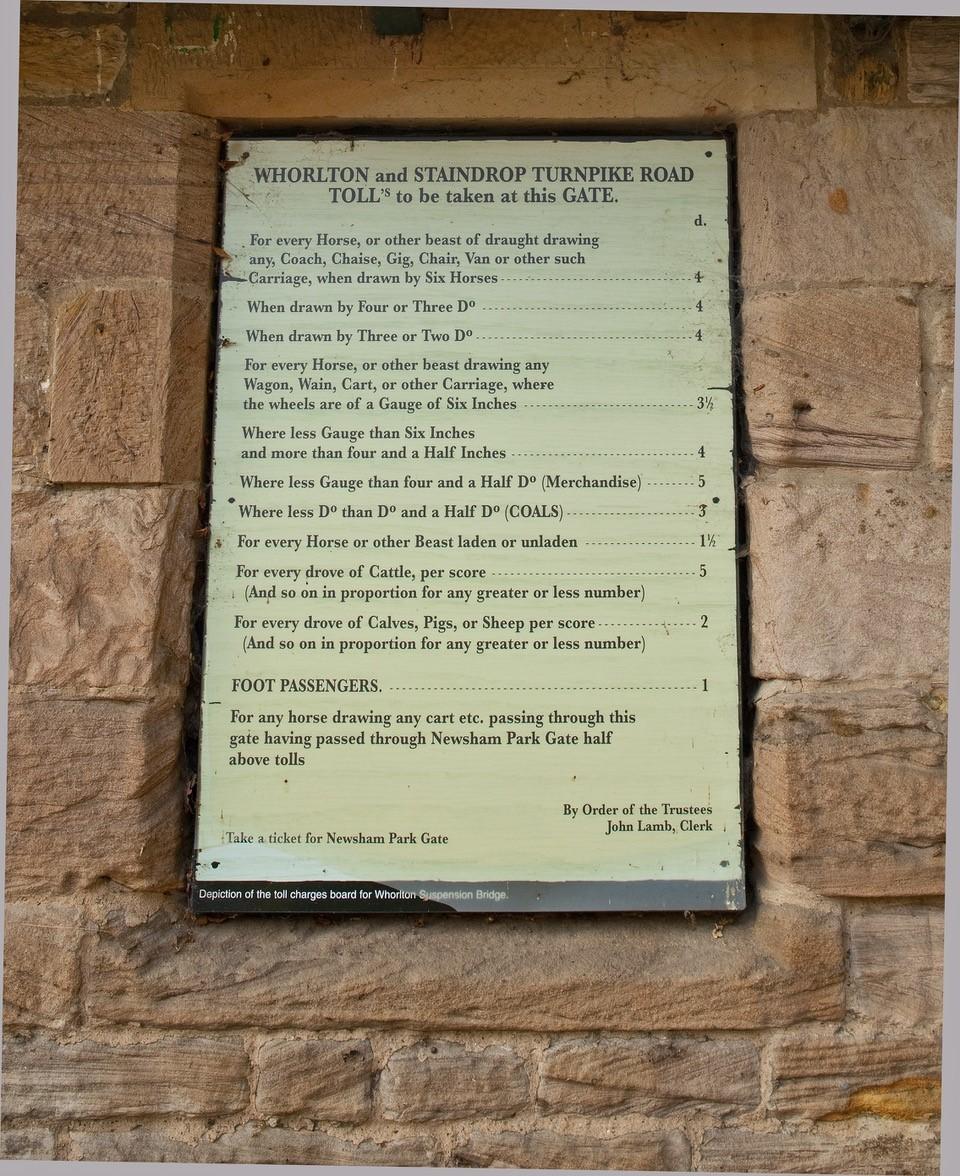

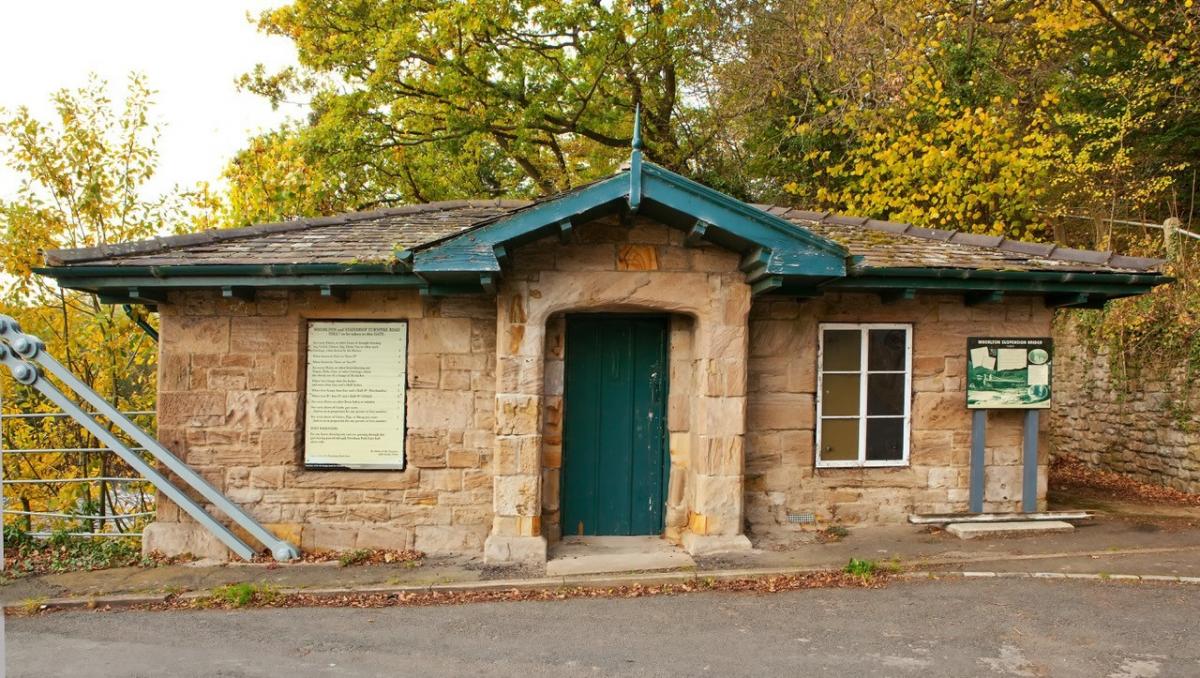

But they lived at Graft’s Farm on the Durham side of the river opposite Wycliffe, about a quarter-of-a-mile downstream from the Whorlton suspension bridge which featured here last week. The ground-breaking bridge, now closed, had been built in 1830, effectively replacing a ferryboat which crossed ay Wycliffe. The boat, though, remained, for private use – for people like William who worked in the sawmill on the Yorkshire side.

When they arrived at the boatman’s house, the river was “in great flood”, according to The Northern Echo. Louisa wanted to go round by the suspension bridge; the boatman, William Barningham, also wanted to go round by the bridge, but Mr Harrison jumped in, loosened the boat’s rope and shouted to his wife: “Come on, here, and get in.”

“You may say he had had a glass or two, but he was always in jolly good heart,” said the boatman later.

Fatefully, Louisa gave in and got in, and so Mr Barningham reluctantly joined them.

They’d nearly made it across, when a great roll of water swept them away, capsizing the boat as it flashed over some rocky falls.

“The boat went over on her side, and I was overhead in water,” said Mr Barningham. “I stuck to the boat, and she came right again. I never saw anything more of them. How I got out I cannot say…”

He lay, exhausted, in a field near Wycliffe Hall.

The Teesdale Mercury, with language as free flowing as the river, said: “Not a sound was heard above the mighty rushing of the river, the bosom of the torrent being now and again illumined by the fitful moonlight. The man who had experienced this hairbreadth escape, now awe-stricken and lonely, began to look about for his missing companions. Alas! The search was fruitless!”

The greatest part of the tragedy was their six children, now orphans. The oldest was 12, and the youngest just three.

Louisa’s body was found half buried in sand about two miles away near Ovingham.

“Many were the sobs and tears of the bystanders who remembered that the breadwinners of a helpless family had, in the twinkling of an eye, been summoned to the silent world,” said the Mercury, wringing every droplet of emotion from the occasion.

Mr Harrison’s body was found ten days later. It had been swept through Gainford and Piercebridge before coming to rest on gravel beds near Cleasby, on the edge of Darlington.

The coroner concluded: “It was entirely owing to this man’s reckless conduct that this sacrifice of life has taken place. It is a very sad, sad thing.”

Louisa and William were buried in Forcett churchyard.

Immediately, led by General Blair, of Thorpe Hall, the communities of Teesdale and Darlington rallied around the orphans, donating generously to a fund.

But nothing could make up for the terrible loss of their parents to the Tees’ watery grave.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here