The second instalment of the Bill Blenkinsopp story begins with the accident on the way to the races which almost claimed his life.

‘This is why I’ll always have money,” says Bill Blenkinsopp, handing me a small, brown envelope.

At first I can’t see anything, but then something catches my eye.

I take it out of the envelope, but I still can’t quite work out what I’m looking at.

“It’s a pound note,” says Bill, 72, who lives in Aycliffe Village.

And so it is. Folded and charred, but unmistakably a pound note.

Apart from himself, it’s the only thing remaining from a horrific car accident more than five decades ago which killed a man and left two others fighting for their lives – and Bill keeps it to remind him of the day that changed his life forever.

Yesterday’s Memories told the story of Bill’s early years as a jockey.

After a stuttering start to the career he had always dreamed of, the then 17-year-old Bill had landed a job as an apprentice with trainer Buster Fenningworth, master of Bell Isle and Hurgill Lodge stables in Richmond, North Yorkshire.

Everything appeared to be going in the right direction for Bill. He was getting plenty of rides and had landed his first winner. And he had a sideline as an amateur boxer, winning the national Stable Lads’ Association Boxing title in the seven stone weight division.

But all that changed on Saturday, April 22, 1967.

Bill was travelling to Ayr races with Mr Fenningworth and stable jockey Albert ‘Brig’ Robson.

It was a big day for Bill as he had been due to ride the red hot favourite, Aldburg, in a £1,000 race – and he was supremely confident of riding the winner.

But as their car reached Ecclefechan, a small village near Dumfries in the south of Scotland, disaster struck.

Fenningworth, who was driving the Aston Martin, lost control. The car ploughed through a crash barrier, plunged 20ft down an embankment and burst into flames.

“It just kept rolling and rolling and then it exploded,” recalls Bill.

“How I got out of it, I’ll never know.”

Driver Fenningworth and front seat passenger Robson were thrown from the vehicle, but Bill remained in the wreck.

All three were transferred to Dumfries Hospital, but Fenningworth was so badly injured he died en route.

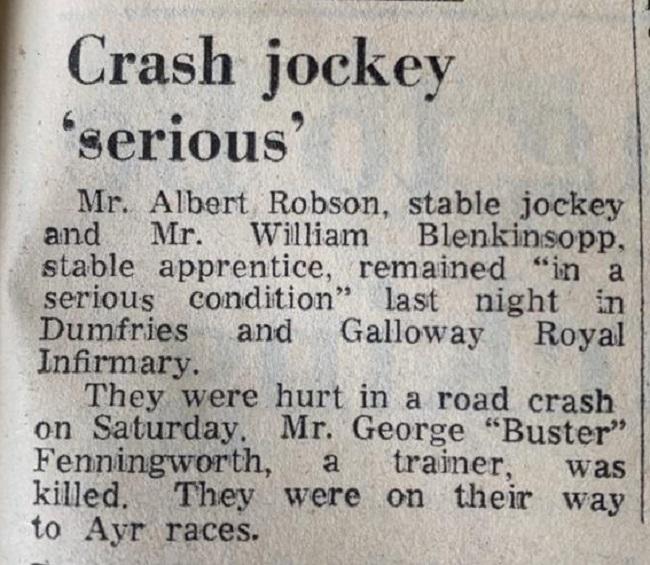

Both Blenkinsopp and Robson, 25, were described as “very critical”.

Bill was not expected to survive. He suffered 68 per cent first degree burns and was given two hours to live “ at most”.

Newspaper reports in the days that followed reported on his progress, but while Robson was improving, there continued to be “no change” in Bill’s condition and his prognosis looked bleak.

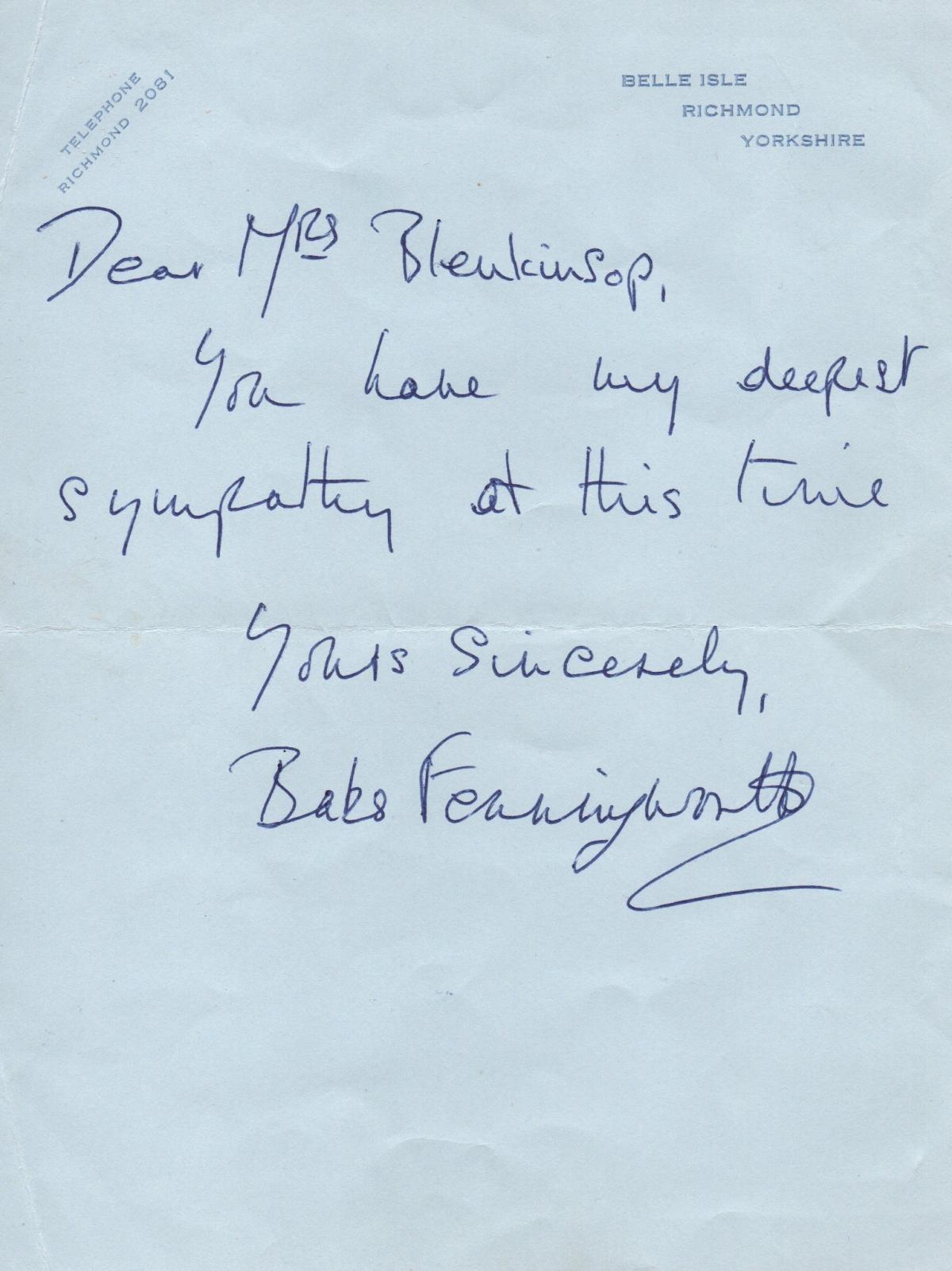

Fenningworth’s wife Barbara, despite her own grief, sent a letter to Bill’s mother which read: “You have my deepest sympathy at this time.”

But Bill didn’t die and gradually – very gradually – he improved.

His recovery was slow and painful, especially the series of painful skin grafts he had to endure every two weeks.

“I had to just grin and bear it,” he says, stoically

His burns were so extensive, that the only ‘live’ skin he had was a small square at the base of his collar and below his right eye.

Surgeons had to turn to his brothers – Jim, Edwin and Peter – for healthy skin to graft onto his wounds.

In hospital, Bill’s weight had plummeted to 2st 8lbs. It was eight weeks before he was allowed to see himself in a mirror. He had to learn to walk again and it was 18 months before he could hold a cup.

One memory from his recovery which has stuck with Bill is the day he received an unexpected visit.

He was at home in Aycliffe Village when a large car pulled up.

“It was a Rolls Royce,” says Bill. “The village had never seen a Rolls Royce before.”

There was a knock on the door and the visitor identified himself as Will Sherman, of Sherman’s Football Pools, and also a representative of the Anglo-American Sporting Club, the powerful sponsors of the Stable Lads’ Boxing Association boxing championships he had won the year before.

“He came to invite me and my brother down to present the cup I had won the year before to the new champion,” says Bill.

His injuries meant he was unable to attend, but it was an act of kindness Bill would never forget. And it was the first of many.

At the boxing championships that year, a bookmaker named Tommy Marshall, who had presented him with the cup the previous year, got together with other bookmakers from Scotland and the North to open a fund for Bill, presenting him with a cheque for £215 before Christmas.

Northern jockeys opened another fund, raising £400. A golf match between sides representing flat race jockeys and national hunt jockeys was organised.

Perhaps most remarkably, Yorkshire wicketkeeper Jimmy Binks help to arrange a charity cricket match between a Yorkshire XI and a team of northern racing personalities.

The game attracted several well-known personalities, including Leeds United footballer Jack Charlton.

Incredibly, the a crowd of 1,400 saw Big Jack bowl out Geoffrey Boycott and another Yorkshire cricketer. Peter Chadwick, in the same over.

Bill knew nothing of this, as he lay desperately ill and sedated in his hospital bed.

But as he gradually recovered, he harboured dreams of returning to the saddle, or at least returning to horseracing in some capacity.

Doctors severed the tendons of his hands and stitched them together again in an effort to restore the use of his fingers and gradually Bill adapted to a new way of life.

He did stay connected to horseracing, including doing some work for trainer Denys Smith at Bishop Auckland, helping to saddle a horse named Foggy Bell which went onto win the Lincoln handicap at Doncaster.

But he never fully realised his dreams of returning to the saddle as a professional jockey and says he is still “gutted” to this day he was unable to go back to that life.

Despite the loss of his chosen career and the injuries he suffered, Bill still has a lot to be grateful for and has a special word for the NHS professionals who saved his life all those years ago.

He says there were two doctors who attended him after he was first taken off the ambulance in Dumfries.

On seeing the extent of his injuries, one thought the best course of action was to amputate both of his legs.

But the other disagreed, arguing they could open his legs and let the fluid run off. Thankfully for Bill, this second view prevailed and he has nothing but praise for the care and treatment he received.

“The NHS were, and still are, absolutely brilliant,” he says.

Bill still keeps hold of his memories of those days when he was a jockey – and a boxer.

He has the trophies he won – a little battered and bruised now – and a scrapbook full of press cuttings, photographs and letters.

And there is that pound note – expenses he was given to cover the costs of his day at Ayr races.

It was recovered from the back pocket of the jeans he was wearing that day, placed in an envelope stamped with the words “on police service” and handed to his mother.

He’s kept it safe ever since.

“It’s why I’ll always have money,” he says again, perhaps remembering what could have been.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel