ON a November day in 1606, wealthy Richmond draper Robert Willance was out hunting on horseback in Swaledale when suddenly a mist arose and a fog descended.

He turned for home, but visibility decreased as the light faded, and horse and rider were left fumbling in the fog...

Near Whitcliffe Scar, which when not fogbound has spectacular views over the dale, something spooked the horse. It took two huge bounds, and then an enormous leap which launched it off the side of the scar, and plunged it 212ft to the bottom.

The horse was killed outright, and Robert’s leg was badly broken.

Night fell.

Robert knew no one would find him before daybreak, and he knew he had to keep warm if he was to make it until then.

So he used his hunting knife to slit open the belly of his horse and he placed his damaged limb inside the carcass.

Next morning he was found alive, still half in and half out of the deceased beast, and he was carried home to Frenchgate. The last vestiges of warmth from the poor animal had prevented infection from creeping in to his leg, but doctors found it to be so badly damaged that it had to be amputated. The limb was then in St Mary’s churchyard at the bottom of his garden.

But Robert recovered his health, and in 1608 became an alderman.

He was so grateful for his survival that he placed a monument on the spot on Whitcliffe Scar from which his horse had taken its last, remarkable leap. It is also believed that he placed three stones 24ft apart which marked the two huge bounds that the animal made before that final leap.

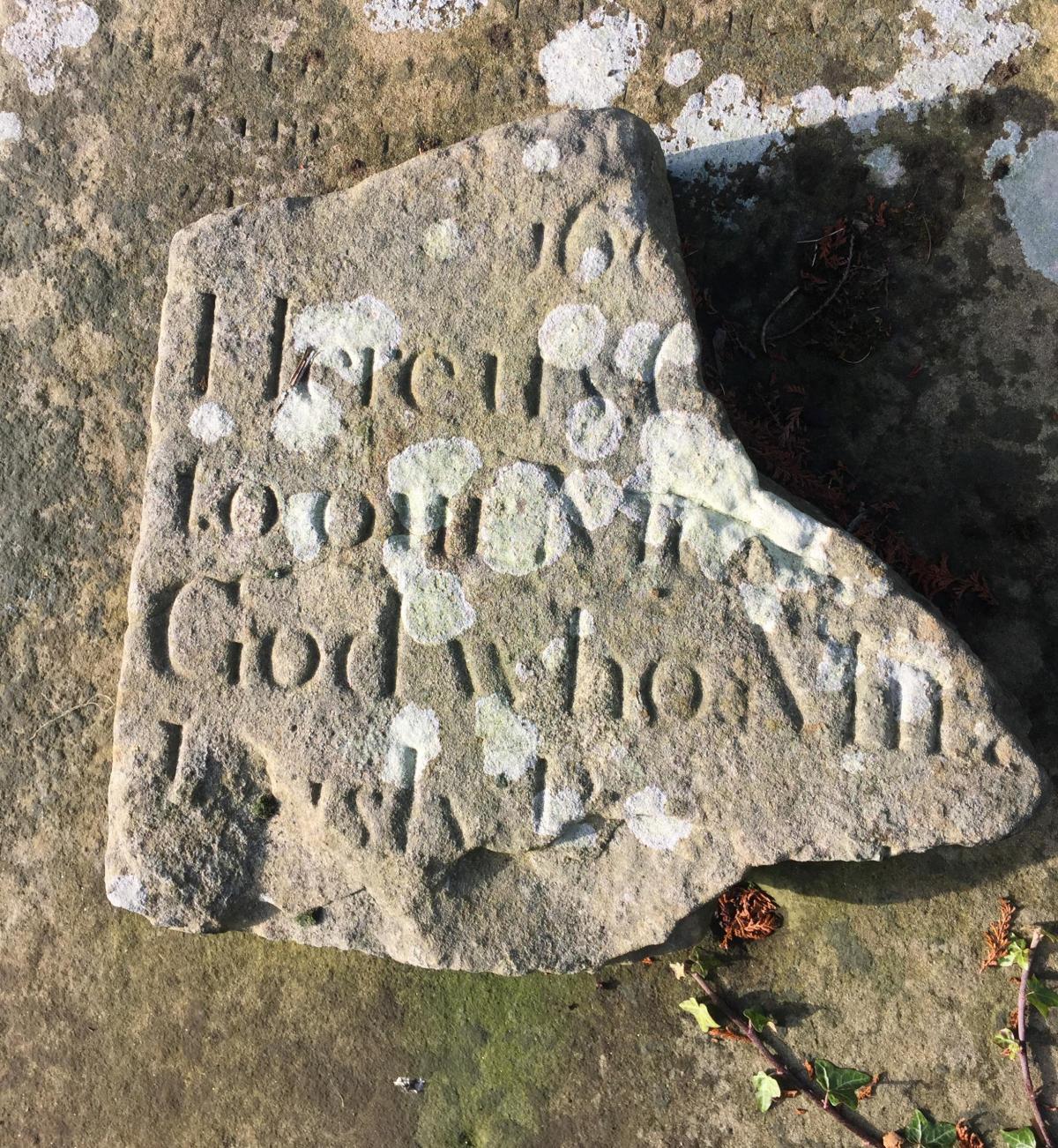

He had the mason carve a legend on the stones: "1606. Glory be to our merciful God who miraculously preserved me from the danger so great."

The stones have become lost and been replaced on several occasions over the centuries, and the story has been embroidered by each retelling.

Robert died in 1616, 10 years after his accident, and he left an estate valued at £1,109 (the Bank of England Inflation Calculator reckons that’d be worth about £300,000 today). Although married to Elizabeth, he left no legitimate children – the will hints at an illegitimate son and daughter, who were left £300 and £100 respectively – and the bulk of his estate was inherited by a nephew.

He also left 20 shillings to be distributed for the next 13 years at Christmas to "poor widows and the aged poor", and a similar sum for "the needy at Winster, Crook and Croft" (Winster seems to be a village in the Peak District). On the day of his funeral, each poor household in Richmond received 12 pennies and every mourner attending was given a penny and dinner.

In death, he was reunited with his leg: he was buried alongside it in St Mary’s churchyard at the foot of his garden.

In 2006, the Civic Society commemorated the 400th anniversary of his leap by placing a silver plaque on his headstone.

WE tell the tale of Willance’s Leap because in Memories 494 we told of the new book about Timothy Hutton, the squire of Downholme, near Richmond. His brother, Sir Matthew Hutton, died in 1814 and was buried beneath a daletop obelisk at Marske.

After that article, Mark Robertson got in touch because, in his distant youth, he had been told a different story about why a stone stands prominently above a drop in Swaledale – a gory story, about a huntsman slitting open his horse’s belly.

“I think of the story every time we drive from Richmond to Reeth and look again at the monument, which stands out so clearly above the trees - or am I an early victim of fake news?” he says.

No, no, no. There are (at least) two monuments in Swaledale, and the story of Willance’s Leap is not fake news: there is more than enough evidence to suggest that draper Willance did survive a November cliff fall 414 years ago.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here