THE quiet agricultural villages of Hauxwell, Constable Burton and Finghall, between Bedale and Leyburn, must have seemed a world away from the roar of the guns and the industrial scale slaughter of the world wars, but even they were touched by the sacrifices demanded of previous generations.

Despite there only being a few of them, their sacrifices are widespread, from the trenches of the First World War to the Burma Railway of the second, and tell the story of Britain’s involvement in the global conflicts.

“There are only 15 of them, but it is quite remarkable that from the remoteness of North Yorkshire they fought and died in all the services and in almost every theatre of war in both conflicts,” says George Tomlin, who has published a book chronicling their stories in time for Remembrance Sunday.

Traditionally, 12 villagers – including one woman – were remembered locally on plaques and in prayers, but Mr Tomlin’s three years of research have uncovered the stories of three more who gave their lives.

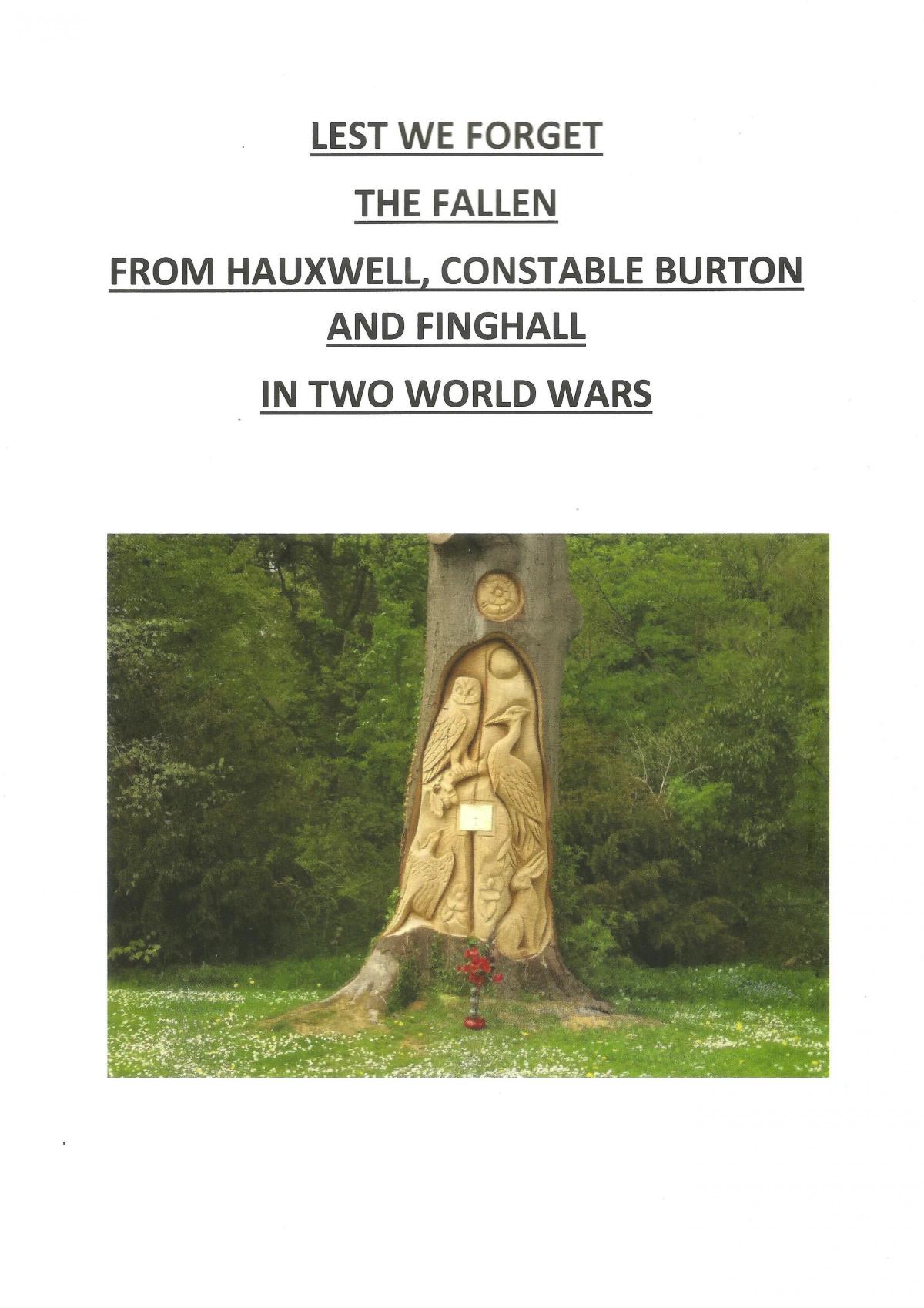

And so, when a 100-year-old beech tree on Constable Burton village green was condemned by a fungal infection earlier this year, rather than cut it off at ground level, the local Wyvill estate based at Constable Burton Hall decided to turn it into a memorial to all 15.

Polish chainsaw sculptor Lukas Beben created a large collage of birds and animals on the tree, and in the centre a memorial plaque has been screwed, recording all the names.

They are from a cross section of rural life.

There are farmers like Pte John Foster, of Garriston, who joined up in Leyburn in 1914, but because of his small stature was posted to a 'Bantam' regiment. He arrived in the trenches of northern France in early February 1916 and survived the Battle of the Somme before his number came up on August 19, 1917.

And there’s Major Marmaduke Wyvill, heir to the Constable Burton estate. His military career included fighting in Tibet in 1904 19,000ft up the Himalayas in what is reckoned to be the British Army’s highest altitude action, but it ended in a military hospital in 1916.

The 100-page full colour book by Mr Tomlin, a retired major who spent 29 years in the Royal Anglian Regiment, is available for £20 from the Tennants auction centre, Hewson’s newsagents and The Old School House, which are all in Leyburn, as well as from the Queen’s Head in Finghall and the Castle Bookshop in Richmond, or by emailing georgetomlin123@gmail.com. Postage will be £3, and proceeds will go towards maintaining the war memorial.

THE SHARPLES BROTHERS

THE Reverend Henry Sharples and his wife, Henrietta, lost the two sons they had brought up at the Rectory in Finghall in the most dramatic of circumstances.

They sent their boys to private schools, as vicars did in those days, and both Thomas and Evelyn joined the services as soon as they turned 18. Neither of them survived three years of action.

The first to die was the eldest, Thomas, 21, who enlisted in the Royal Navy as soon as he left Wellington College in Berkshire in 1913. In 1916, he was a sub-lieutenant on HMS Hampshire and took part in the Battle of Jutland, the only major naval engagement of the war, in which more than 6,000 British sailors were killed off the Danish coast.

Hampshire returned to Scapa Flow, a sheltered body of water off the Orkney Islands, where it immediately picked up Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War and the moustachioed face of army recruiting. He was to be taken to Archangel in Russia to meet the tsar.

As atrocious weather closed in, Hampshire turned back, and just a mile-and-a-half from the shore struck a mine laid by a German submarine about six days previously. It sank within minutes. Only 14 of the 749 onboard survived – most of them escaped the initial explosion but their lifeboats were smashed by the towering waves into the side of the sinking ship, throwing them into the water.

Kitchener’s body was never recovered. His death sent shockwaves through the British war effort and launched a flotilla of conspiracy theories.

Thomas’ body was recovered, and he is buried on the Isle of Hoy.

Eighteen months later, tragedy called once more at the Rectory.

On January 26, 1918, the Darlington & Stockton Times reported: “Captain Evelyn Horace Guy Sharples, 19, the only surviving son of the vicar of Finghall, near Leyburn, was killed when his bi-plane disintegrated in mid-air during acrobatics training.”

Evelyn had attended Haileybury College in Hertfordshire where he had been a member of the Officer Cadet Corps. He joined the Royal Flying Corps – the forerunner of the RAF – just ten days after his 18th birthday.

Within a year, as the death rate among the inexperienced pilots of the Bristol bi-planes was very high, Evelyn had been promoted to the rank of captain.

He served for at least seven months over northern France, and on September 21, 1917, his bi-plane hit a shell crater on landing and turned over, although he and his observer were unhurt.

He was posted back to Biggin Hill to work on a new fighter, the SE5a, but during testing things went wrong.

“On Saturday, January 19, near Biggin Hill in Kent, Capt Sharples had taken his SE5a bi-plane through several evolutions – loop the loops – which he had performed solely for training purposes and not in any way for amusement,” said the D&S.

He levelled out at about 4,000ft “when suddenly his machine banked to the left and started spinning nose downwards. It then flattened out, and the wings collapsed upwards. The machine fell and crashed down upon some houses, piercing the roofs of two of them.”

His body was brought home to be buried in Finghall churchyard on the Wednesday, in a service conducted by his uncle, the Reverend Ernest Orde Powlett, the rector of Wensley.

“The coffin was borne to the graveside by officers of the RFC and after the committal sentences had been said, three volleys were fired over the grave by men of the RFC after which the Last Post was sounded,” reported the D&S of the funeral that was attended by all the leading figures in the dale.

The Sharples brothers are remembered in memorials near the altar of their father’s church.

CPL RAYMOND HARKER

RAYMOND was born in November 1918 just days after the end of the First World War and would die in the Second World War pushing the Nazis out of the Netherlands, probably not knowing that back home in Finghall, his wife had given birth the day before to their daughter.

He came from a large farming family, and in 1943, in Finghall church, married Doris, from Todmorden, who regularly visited her relations in the village.

He joined the Duke of Wellington’s (West Riding) Regiment, and landed on the Normandy beaches on June 11, 1944, a month after D-Day then pushed through northern Europe to take part in the liberation of the Netherlands.

But at 9.45am on October 28, he was one of four men from his battalion’s C Company that was killed by German resistance near the small city of Roosendaal.

It seems impossible he could have known that the day before Doris had safely given birth to their daughter, Jennifer, who now lives in Todmorden.

SISTER ANN WOLSELEY-LEWIS

ANN was part of the large Stirke family, and together with her five brothers and three sisters grew up on a farm at Heselton. She had an independent streak, and aged 17 began training as a nurse at Harrogate before specialising as a midwife in Glasgow.

Aged 23 in 1937, she received a grant which allowed her to travel to take up a post as a staff nurse in Cape Town, South Africa. After 18 months she moved on to Kenya, where she met Arthur Wolseley-Lewis, a coffee planter serving in the King’s African Rifles. They married in 1940.

With Arthur away in Burma, Ann joined the East African Military Nursing Service. On February 12, 1944, she was one of 1,511 people onboard the SS Khedive Ismail, part of a convoy moving British service people around the Indian Ocean. In Ann’s case, she was heading for Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) to tend the wounded.

The steamship had almost made it across the ocean when it was spotted by a Japanese submarine, I-27, off the Maldives.

At 2.30pm on February 12, 1944, the sub fired four torpedoes at the troop ship. Two hit, causing an immediate fire – many of the passengers were below decks watching a concert at the time.

The few survivors spilled into the sea, but with the submarine still lurking directly beneath the survivors, one of the two escorting destroyers, HMS Petard, had to go after it – the sub was still a threat to shipping and Japanese commanders had a reputation for machine gunning survivors in the sea. Petard dropped depth charges which eventually destroyed the sub, but also killed and wounded the survivors.

In all, 1,220 male lives were lost and 77 female. The sinking of the Khedive Ismail was the third largest Allied loss of life from shipping in the war, and the largest loss of female lives.

Ann is remembered in Nairobi and in the church in Finghall.

SIGNALMAN SYDNEY POWELL

SYDNEY was raised by his parents in Hauxwell, and married Muriel from nearby Hunton, who worked as a live-in laundry maid at Thorpe Perrow Hall, where the grounds are now an arboretum.

He joined the Royal Corps of Signals in 1939, and in December 1941 was sent to the Far East. However, as he sailed east so the Japanese were advancing to meet him.

His regiment landed on eastern Java on February 4, 1942, and had just had time to set up an airfield defence when the enemy landed on the north on February 28. They quickly advanced and at noon on March 9, the British surrendered, and Sydney became a Prisoner of War.

He was sent to construct the notorious Burma Railway where, on September 23, 1944, at the age of 32, he became one of the 16,000 Allied prisoners to die due the atrocious conditions they worked in.

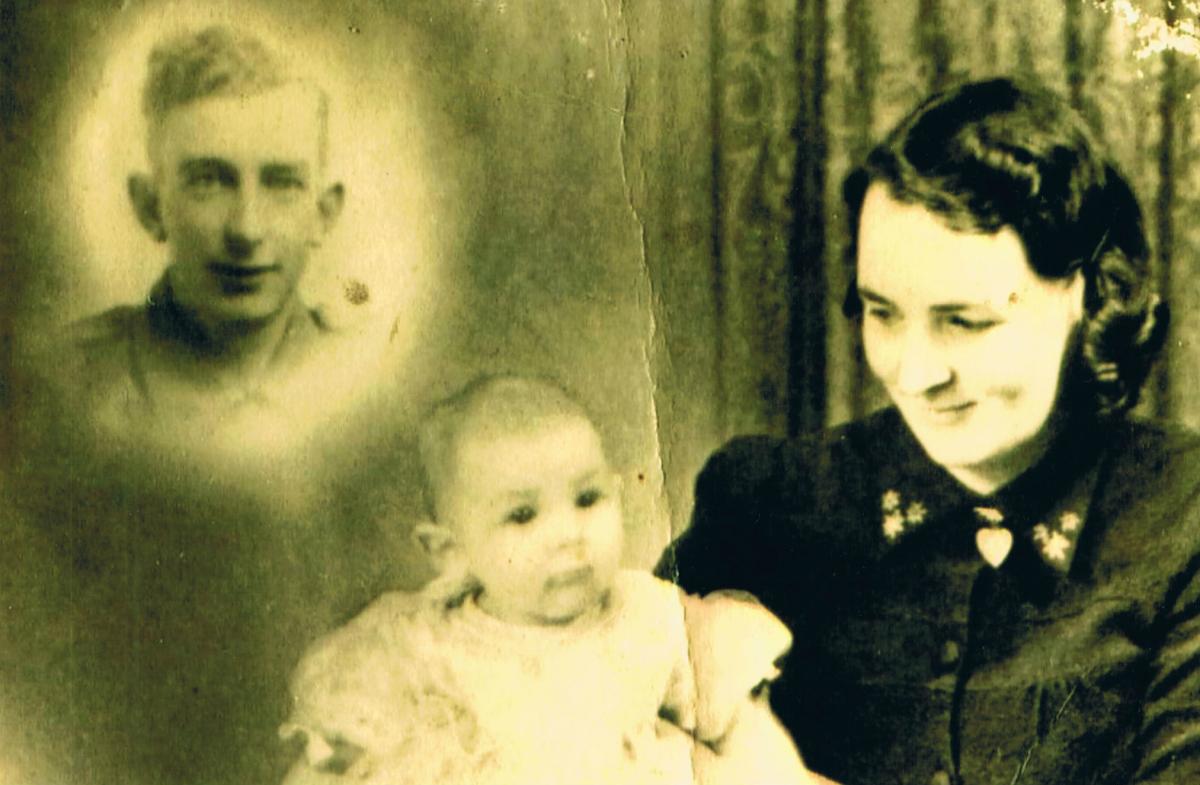

He never saw his son, Sydney, who was born in September 1942.

Even though his wife and son continued to live at Hauxwell for many years, Sydney’s name was never commemorated in his home area. More than 76 years after his death, the new memorial and the book right that wrong.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here