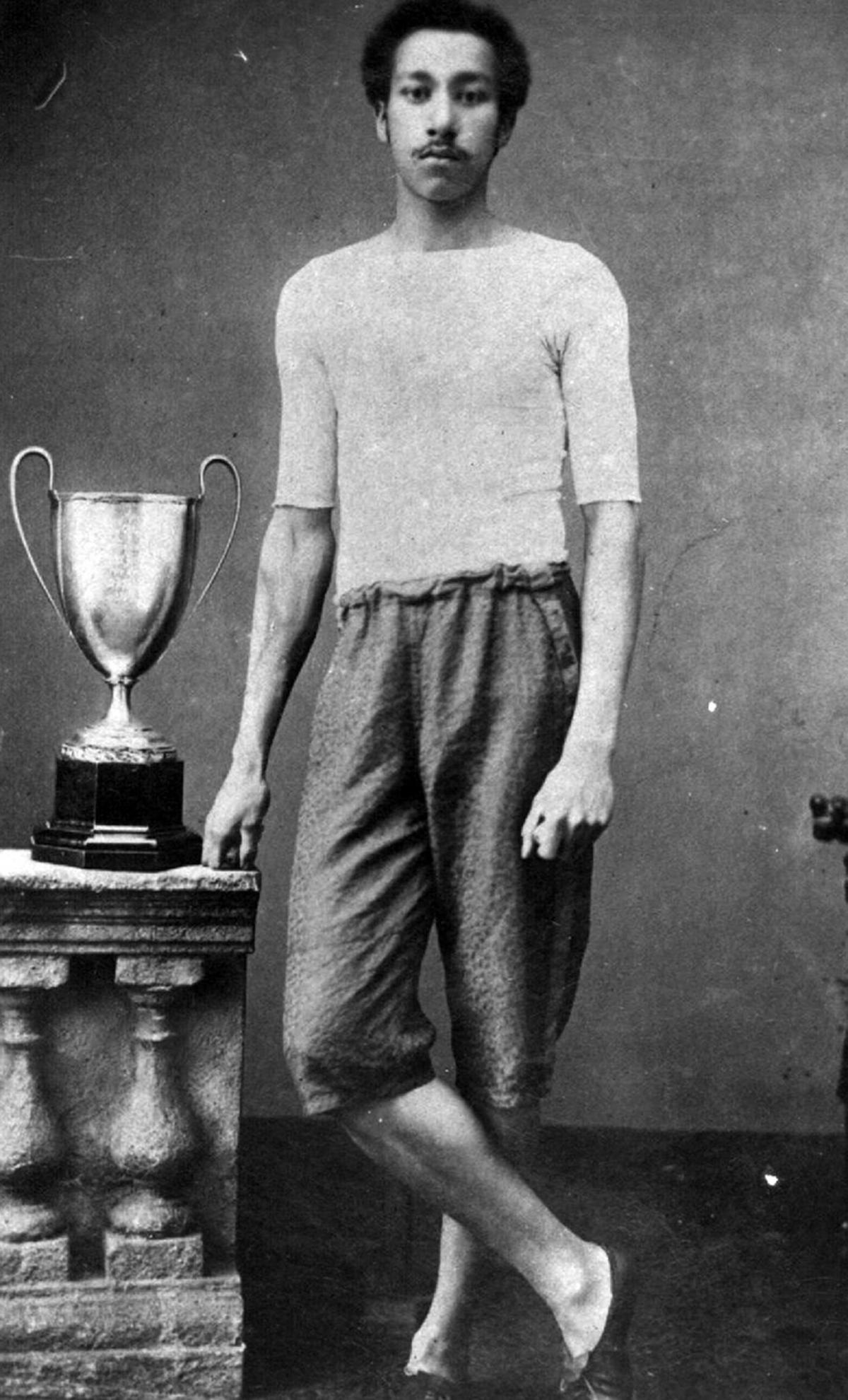

ARTHUR WHARTON was the fastest man in the world. He was the greatest goalkeeper in the country. He was lionised by fans who loved his athleticism and his showmanship, and, wherever he went, he was big box office.

He had many claims to fame – wearing a Darlington Cricket Club shirt, he became the first man in the world to run 100 yards in exactly 10 seconds and, of course, he is renowned as the world’s first black professional footballer.

But when his sporting powers began to wane, he was allowed to fade away into a sad decline of alcoholism and penury until he was buried in an unmarked pauper's grave in South Yorkshire in 1930.

Despite this heart-breaking demise, he was born in 1865 in Accra, the capital of the Gold Coast (now Ghana) in West Africa, practically into royalty. His mother, Annie, was descended from the Fante royal family, and his father, Henry, was born on Grenada in the West Indies, where he was the son of a wealthy Scottish trader.

Henry was a Methodist missionary, and he sent 17-year-old Arthur to England for a Methodist education, first in Staffordshire and then, from 1884, at Cleveland College, a private school off Milbank Road in Darlington.

In May 1885, he entered the sprint in the Darlington Cricket Club sports day at Feethams, but when he reached the tape, he ducked underneath it because he had never seen such a thing before. His style – the Darlington & Stockton Times described him as running like “an express engine with full steam on” – and his attitude – in June 1885, he angrily smashed his prize of a salad bowl after a race in Middlesbrough – and, of course, the colour of his skin, made him an immediate local celebrity.

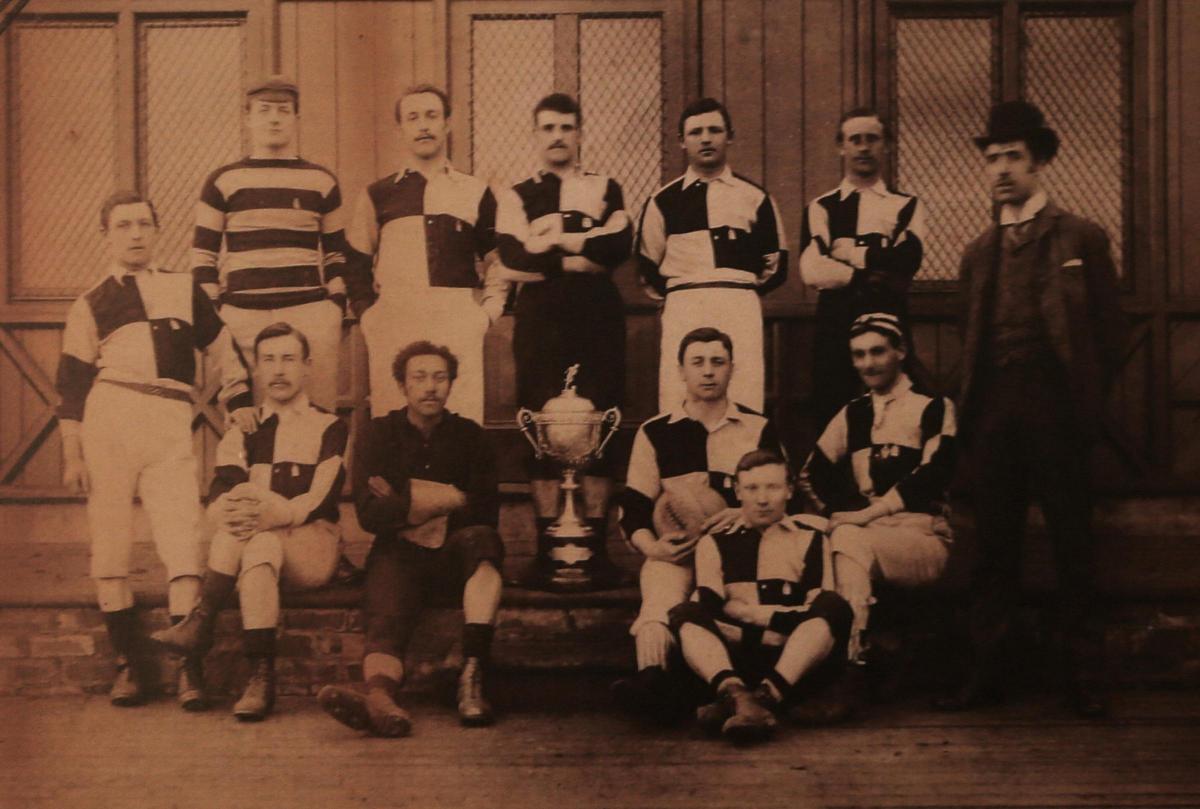

At the end of the 1885 summer running season, Arthur joined Darlington FC, as a goalkeeper, and he played about 20 games. Violence against keepers was then quite legitimate, and Arthur would crouch at the foot of the post, away from the flying boots, and at the last moment leap to clutch the ball.

"He earned fame as a brilliant goalkeeper," said the Echo in 1913. "He could fist a ball almost as far as a man could kick it." He could also swing from the crossbar and catch the ball between his legs.

In July 1886, Arthur entered the Amateur Athletics Association championships at Stamford Bridge as a representative of Darlington Cricket Club. He astounded the 2,000 crowd by winning both his 100-yard heat and the final in ten seconds dead - the first time anywhere in the world this had been reliably recorded.

Wherever he went, he was big box office, reaching the FA Cup semi-final as an amateur (with sizeable expenses) with Preston North End, one of the biggest clubs in the country. He returned to help the Quakers in the semi-final of the Durham Cup – he was described as "impassable...miraculous" – but missed the final, which Darlington lost by the only goal of the game due to sudden illness.

In the summer of 1887, he retained his AAA title, and he cycled from Blackburn to Preston in a record two hours - he would have been faster but as a novice on the new-fangled tricycle, he kept overturning it and falling off.

When he finished at Cleveland College, he broke with his family’s wishes to become a missionary and instead went to Sheffield to be a professional sportsman, but his career never quite took off. He had six seasons as pro goalie with Rotherham Town in the Midlands League – his wife, Emma, came from Rotherham – and when Sheffield United offered him a First Division contract, he was unable to dislodge their keeper, William “Fatty” Foulkes, from the first team. However, he did play in a match versus Sunderland in 1894-95, making him the first mixed heritage player to play in the highest league.

Arthur ended up at Stockport County where, in 1902, Britain's first black professional footballer played his last football league match in the Second Division against Newton Heath (who would become Manchester United).

He stayed in south Yorkshire, working in a colliery haulage department and running pubs, and supplementing his income by turning out in the local football and cricket leagues.

There's an air of sadness to his life. He seems detached from his wife and daughter, unable to return to Africa, unable to find permanent sporting employment, unable to beat illness, be it syphilis, cancer or alcoholism.

He visited Darlington in 1913 when his job as coach at Burnopfield Cricket Club fell through, and he told The Northern Echo: "I always think that Darlington is one of the finest towns in the world, and I hope I may stay if circumstances permit."

They didn't. He returned to south Yorkshire and faded away until he was buried in a pauper's grave, in Edlington.

In 1997, a headstone was erected by anti-racism campaigners, and in 2003, he was inducted into the English Football Hall of Fame, and a campaign by Shaun Campbell has enabled his story to reach the ears of sportsmen all over the world.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel