FOR Jacob Tucker, there was no going back. He sold his shoemaker’s business in Kingston, Jamaica, and with the proceeds bought a ticket to the UK. He said farewell to his wife and three young children, and set sail for a better life.

He’d probably seen an advert in the Jamaican newspaper, The Gleaner, in which the British government was appealing for skilled labourers to come from Commonwealth countries to help rebuild the British economy after the Second World War.

The first people to respond to the call arrived at Tilbury Docks on MV Empire Windrush on June 22, 1948. Jacob sold up and sailed in 1956.

“When we were children,” says his daughter, Ann, “we were told that the streets of the UK were paved with gold and he came for a better life.”

Jacob had hoped to start up again as a shoemaker, and his fellow travellers had dreams of becoming electricians and cabinetmakers, but when they set foot in Britain, those jobs weren’t available.

Instead, Darlington council was advertising for men to work on its buses, and so the first group of about eight West Indians arrived at Bank Top station in the spring of 1956 ready to start work.

Darlington wasn’t quite the promised land – it’s streets were more likely to be covered with snow than paved with gold.

The new arrivals were put up in temporary accommodation inside the bus depot at Feethams, where they worked as cleaners and conductors.

Gradually, they saved money, and they rented and then bought houses in East Mount Road where a West Indian community developed.

“We were at number 24, the Henrys were next door, and then there were the Webleys and the Thompsons,” says another of Jacob’s daughters, Patricia.

For many of this community, the United Reformed Church in Northgate became their spiritual home and the Darlington workingmen’s club their social scene.

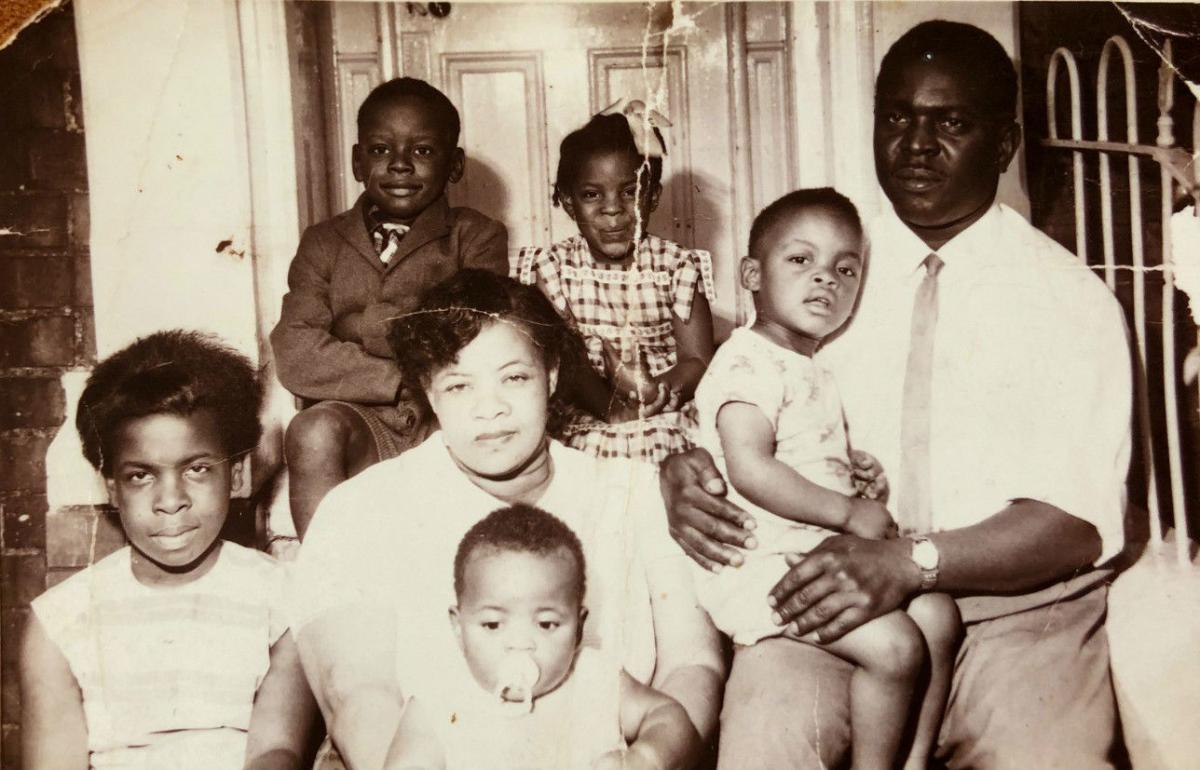

As the men established themselves, they brought their wives over from the Caribbean, which meant their children were left with their grandparents until finally the full families could be reunited. Ann and Patricia lived in rural Jamaica where their grandmother was a midwife and their grandfather was the district constable – they didn’t have running water or electricity, but they were warm and comfortable.

“I came to the UK in 1964, when I was about 11 or 12, and that was the first time I had seen my parents since they had left,” says Ann. “When I arrived, it was cold, but I loved the snow, and the houses were like factories with smoke coming from their roofs.”

Patricia and Elaine followed in 1969 – Patricia had been only months old when her father had left and she didn’t see him again for nearly 13 years. Suddenly she found she had a large family: Lloyd, Beverley, Victor and Yvonne had been born over here, and so they must be among the first Darlington-born black people.

Ann went to the North Road Girls Secondary School which in 1968 moved to Longfield Road as a comprehensive.

“I was the first black pupil, they had never seen a black person before,” she says, “and they asked me if I had red blood like them, and if I went to the toilet like them! The teachers were lovely. It was a positive experience.”

However, life had its hard times. Patricia remembers being scared some nights to go out to play as there were fights and thrown stones, and Jacob had a particularly unpleasant experience with Darlington police in the 1980s.

Jacob left the buses to work as a kitchen porter at Catterick and then returned to Darlington for a job at Cummins. Bernice, his wife, worked at GEC, a company which made telephones in Aycliffe. They bought a bigger house, in Hewitson Road.

Patricia, like so many female Darlingtonians, found her first job at Patons & Baldwins, the largest wool factory in the world at Lingfield Point. She moved on to Astraka, the fake fur manufacturers at Shildon, and then back to P&B.

Ann went to Leeds to train as a nurse, and returned to work at the Memorial before starting to specialise at the Hundens unit.

In 1977, she made front page news in the Echo’s sister paper, the Evening Despatch, when she got married at the URC to Cleavan Weekes, who hailed from St Kitts – the prominence of the photograph suggests that black weddings were still unusual.

Ann and Cleavan went off to London, and she now has two social work degrees.

Jacob and Bernice remained in Darlington until they died in the 1990s, and now these pioneers have great-grandchildren in the town. They include a nurse, a doctor, a male model, a boxer, a gym owner, an actress...

“My parents had to get used to being in a new country, to the people who didn’t know them, didn’t understand them and didn’t know why they were there,” says Patricia. “They were forever getting used to the cold, they had to lots of barriers to come through and they had to fight much hatred and upset, but the Lord was always there.”

Yvonne Cherrington, the youngest of Jacob and Bernice's children who was a non-executive board member of Darlington Primary Care Trust, says: "Our parents came here to the “promised land”, for a better life for them and their family, and I think they achieved it. What a treasured lives we’ve had in Darlington!"

L Pat’s daughter, actress Alicia McKenzie, has made a moving video about her story. It can easily be found on YouTube by searching for Alicia’s name and the title, Uprooted

“EVERYTHING was very strange,” says Faye Richardson, remembering the moment in 1965 when, aged 13, she touched down in the chilly country that would become her home.

“My parents picked me up from the airport at Manchester, and the first thing I noticed was the chimneys. I was thinking there’s lots of bakeries, they must eat a lot of bread in this country, because in Jamaica the only buildings that had chimneys were bakeries, and my mum said no that’s houses, we have to have heating in this country because its cold.”

Her father, Alfonso Lennard Webley, had come over in 1958, leaving his wife, Gwendoline, and three young children in Jamaica. His father was already in London and “received” him, but Alfonso made his way to Darlington to work on the council buses, first as a conductor and then as a driver.

He lived at first in East Mount Road, and then Gwendoline came over and they bought a house on Albert Hill. By the time Faye and her brother Junior came over in 1965, there were six children in the family.

“The food was strange: we were used to yams and breadfruits,” she remembers. “We had fish and chips shortly after I arrived. I wasn’t used to fish that way and I thought ‘they eat a lot of Irish potatoes in this country’.”

Faye attended North Road Girls Secondary School. “I didn’t experience much or any racism, maybe I was ignorant or it wasn’t that blatant,” she says. “People were more curious about where we came from and what it was like.”

She left school at 16, worked at Patons & Baldwins and then joined her mother at GEC making telephones in Aycliffe. When she married in 1975, she moved to London, although two of her brothers, Junior and Barrington, are still in the town.

Alfonso left the buses and successfully set himself up as a French polisher in a yard beside Binns off High Row. When he retired in 1992, he and Gwendoline returned to Jamaica, where she died in 2002. Alfonso died in 2012, aged 83.

“I cannot have been easy to leave a young family and come over here by himself where he knew no one, but I never heard him complain about it,” says Faye.

It must have been a huge decision for these families to leave everything behind and sail to the other side of the world, and although life was hard for them, they helped make Darlington the town it is today.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel