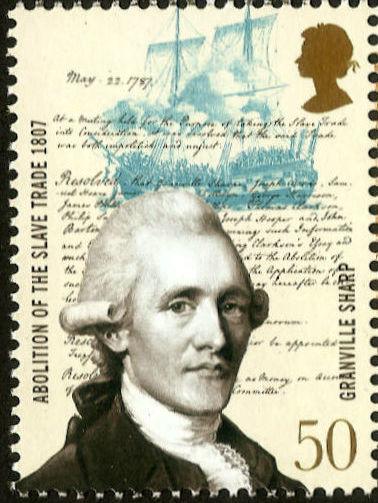

IT is a long way from the white sandy beaches of Montego Bay in Jamaica to the grey slate roofs of Durham Town Hall, but both places remember Granville Sharp.

On the edge of Montego Bay is a place named Granville after the anti-slavery campaigner who is remembered in his birthplace with a plaque in the town hall.

Granville was born in the city on November 10, 1735, the youngest of nine sons of the Archdeacon of Northumberland (he was also a grandson of the Archbishop of York). He attended Durham School, but as he was the ninth son, his parents had run out of money to pay for his education by the time he came along, and so, aged 15, he was sent to London to become an apprentice draper.

One of his brothers who had been more fully educated, William, had become a doctor in London, and he treated poor people for free one day a week with Granville helping out. One day in 1765, a black man, Jonathan Strong, presented himself to the brothers as he had been badly beaten.

Jonathan was a slave from Barbados whose owner, David Lisle, had brought him to London. Jonathan had got himself baptised – some slaves mistakenly believed this set them free – which prompted Lisle to beat him brutally in the street.

The Durham brothers paid for Jonathan to spend four months in hospital recuperating, but when he’d recovered, two of Lisle’s slavecatchers pounced on him and dragged him to a ship to sail him back to Jamaica.

Granville immediately immersed himself in the law, trying to prove that Lisle had no right to own the black man in England and so was falsely imprisoning him.

Amid tumultuous scenes, during which Granville declined to duel with Lisle, Strong was released.

Supported by his brother, Granville worked full time on the legal campaign until Lord Mansfield delivered a judgement in 1772 which agreed that there was no legal basis for slavery in English law. Effectively, this set every slave in England free, and is seen as one of the first key moments in the fight against slavery.

In 1781, Granville threw himself into another campaign, trying to get the owners of the slave ship Zong tried for murder. The Zong had sailed from Africa so over-crowded with slaves that it began to run out of water mid-voyage. To save themselves, the crew had thrown 132 members of the cargo - humans - overboard to their deaths. The Liverpool owners of the ship tried to claim against their insurance company for their losses.

Granville couldn’t get the murder charge to stick, because the slaves were regarded as the owners’ property, but in 1787, he was one of the 12 founders of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade which, in 1788, had its first success with the passing of the first law regulating the slave trade and the number of slaves who could be crammed onto one ship.

Granville drew up a plan to create a model settlement in Sierra Leone, on the African coast, so black people – usually ex-slaves – who had ended up in England could return home. He called it “the Province of Freedom”, and he persuaded the British government to pay each returnee £12-a-head to go.

The first 400 sailed in 1787, and when they arrived, they began creating their utopian home in Granville Town.

However, the local chief burned Granville Town down.

Undeterred, Granville had another go, and in 1792 Freetown was established on the site of Granville Town, and it is still the capital of Sierra Leone.

Granville died in Fulham in 1813, but he is remembered in his birthplace by a plaque that was placed in the town hall in 1979, and by his old school.

THERE is already one blue plaque in the centre of Sunderland dedicated to an anti-slavery campaigner. Next week, it will be joined by a second.

The first plaque is to James Field Stanfield, who was born in Dublin in 1749. He was prepared for the priesthood but took to the sea instead. In 1774, he sailed from Liverpool to Benin, on the west African coast, where he waited for eight months while enough black people were captured to make the voyage to the Caribbean worthwhile.

He was so outraged by his experiences on that voyage – he bandaged a black woman who was beaten till her back was full of holes by the captain – that he wrote a series of articles on his return about life in the “floating dungeons”.

His work in the late 1780s laid bare the true nature of slavery and helped Granville Sharp’s campaign as it turned the tide against the trade.

Then Stanfield made a dramatic career change: in 1789, he became an actor and joined Samuel Butler’s company which toured the North Riding. It was Butler who built and managed the famous Georgian theatre in Richmond, where Stanfield appeared on several occasions before he settled in Sunderland where he formed his own company.

He became an influential Wearsider, forming the city’s first library and museum and, in 1810, the Sunderland Literary and Philosophical Society where slavery was one of the topics discussed.

For all of this, on the site of his residence of Bodlefield House in High Street East, there is a blue plaque which describes how he was an “actor, author and campaigner against the slave trade”.

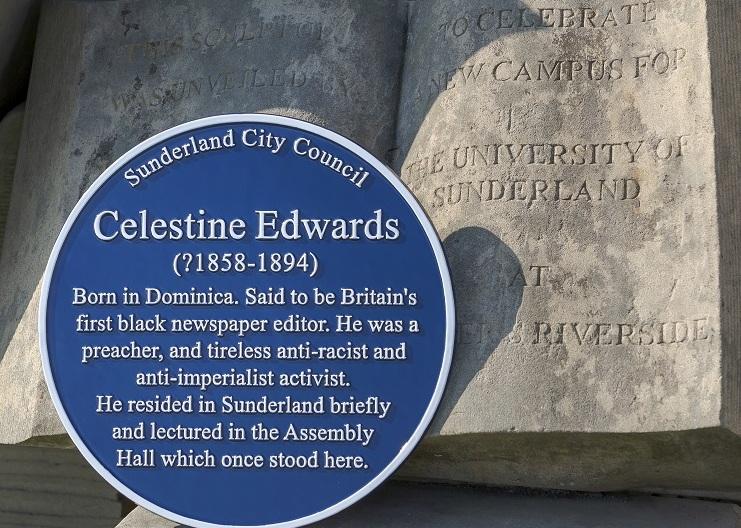

NEXT Thursday, a second slavery-related plaque will be unveiled in Sunderland, dedicated to Celestine Edwards, who was born on the West Indian island of Dominica in 1858.

He became a sailor at the age of 12, made it across to Britain where he settled first in Edinburgh and then came to Sunderland to work as a building labourer.

Sunderland, like much of the North-East, had had many voices against slavery. As well as James Field Stanfield, there were Methodists and Quakers, including Edward Backhouse from the Darlington family of bankers whose brother developed Rockliffe Park, at Hurworth.

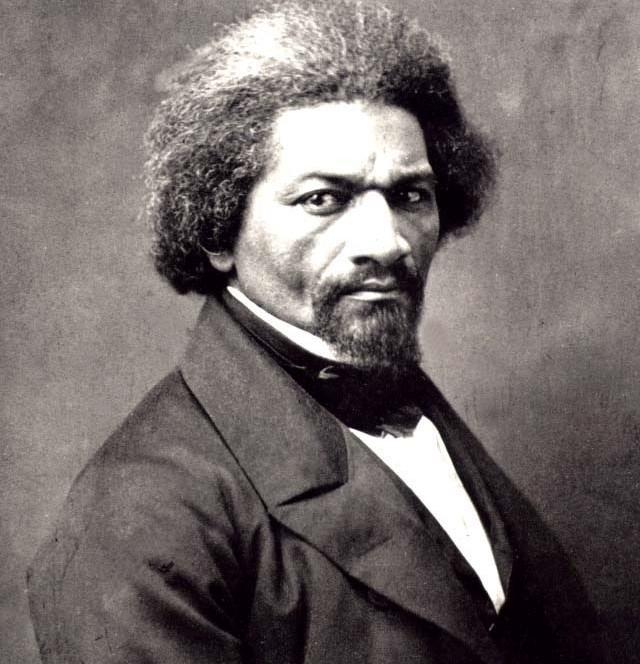

Edwards delivered many of his speeches about the effects of slavery and the racism that followed it in the Assembly Hall in Fawcett Street. He was joined on several occasions by Frederick Douglass, the renowned African-American abolitionist who had escaped from captivity on a Maryland plantation.

Edwards only lived in Sunderland for a short time in the 1880s before he moved to London, where he edited two journals, a Christian weekly newspaper called Lux, and 7,000-circulation magazine called Fraternity. He is regarded, therefore, as the first black editor of a news publication.

He continued to tour and speak. In Newcastle in 1894 he said: “My ancestors proudly trod the sands of the African continent, but from their home and friends were dragged into the slave mart and sold to the planters of the West Indies. The very thought that my race should have been so grievously wronged is almost more than I can bear.”

Professor Angela Smith of Sunderland University, who has researched Edwards’ story, said: “He was so diligent in his activism that he died from exhaustion in 1894 when was not yet 40 years old. It is therefore fitting that we finally recognise his contribution as an impassioned anti-slavery campaigner who, while he resided in Sunderland, had a profound impact on the community in the period of the late 19th century.”

The plaque will be virtually unveiled on Thursday. It will go on the former Midland Bank which is on the site of the Assembly Hall, where Celestine Edwards was a regular speaker. It will be the first plaque to a black person in Sunderland.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel