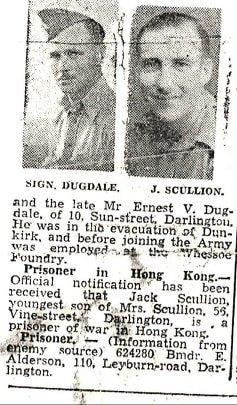

Jack Scullion was a Darlington lad who survived the horrors of a Japanese prisoner of war camp. On VJ Day, PETER BARRON tells his incredible story

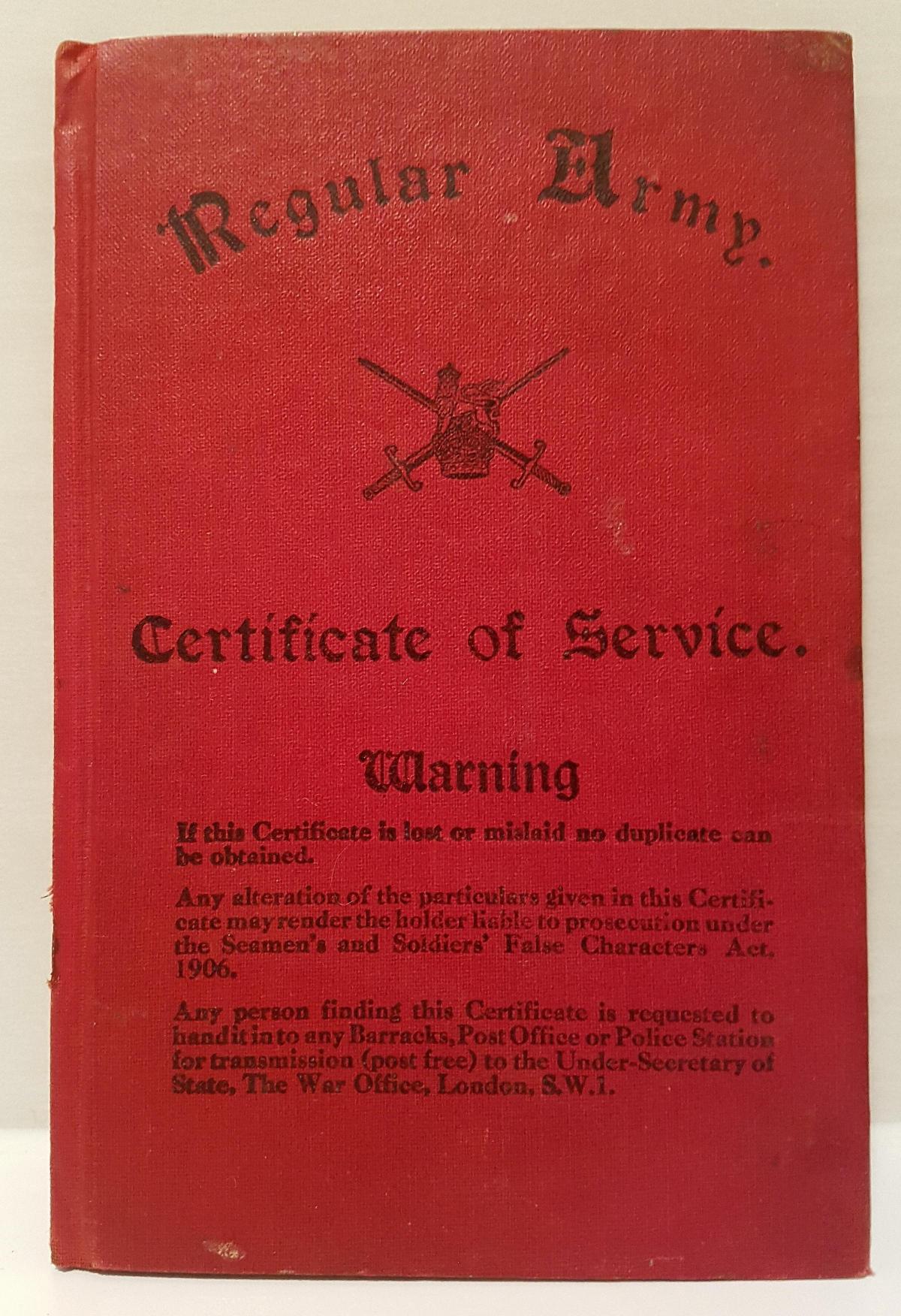

WHEN John McClure Scullion – Jack to those who knew him – signed up for the Army on April 19th in 1937, he weighed 14 stone and four pounds.

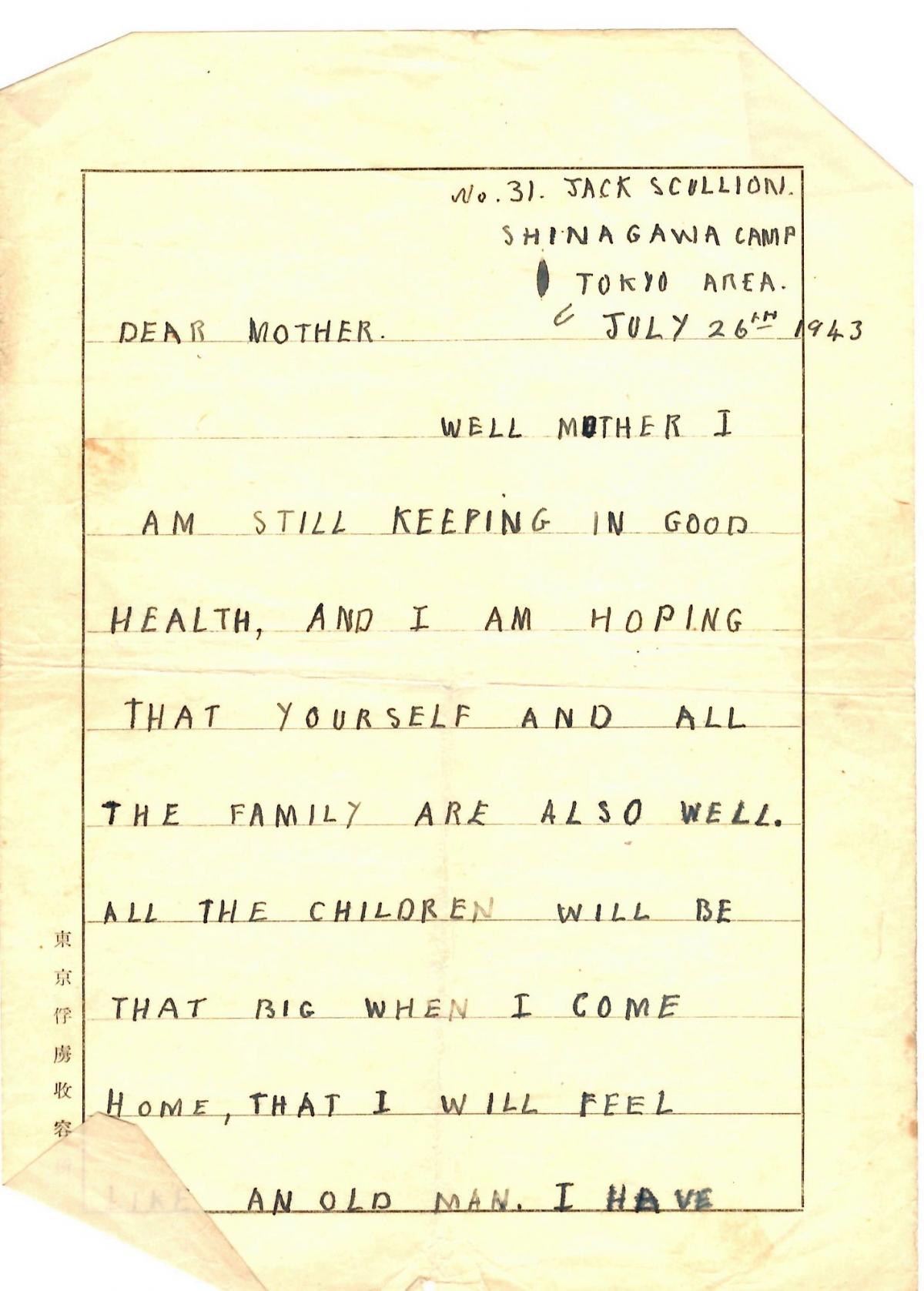

Eight years later, when the war was over and he emerged from the Shinagawa prisoner of war camp, in the suburbs of Tokyo, he was six stone of skin and bones.

For the rest of his life, back home in Darlington, Jack could hardly bring himself to talk about the horrors he’d witnessed, and which still made him scream in the night.

Had it not been for his father’s expertise at making ships’ propellers, Darlington would never have been Jack’s hometown. William Scullion, of Coatbridge, in Scotland, was a renown ‘propeller-wright’ – so good at his job that when Darlington Forge won the contract to make parts for Titanic, a representative was sent north of the border to coax William down to County Durham.

He moved to Darlington in 1910, and his wife, Isabella, forged her own piece of Darlington history by becoming the first female board member of the Co-operative Society. The couple had five sons – though one died at 15 months – and four girls. Jack was the fifth, the first to be born in Darlington, and grew up at 56 Vine Street.

He went to Reid Street School, started work at 14 as a hod carrier for Bussey and Armstrong, and, as the dark clouds of war gathered, signed up for the 7th Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment of the Royal Artillery.

Towards the end of 1937, Jack was despatched to the Stanley Fort garrison, in Hong Kong, where he served until December, 1941, when Japan launched the invasion of the British colony on the same morning as the attack on Pearl Harbour.

Having run out of ammunition, Hong Kong finally surrendered on Christmas Day. Before being captured, Jack used the last round in his weapon to kill his beloved black Labrador, Jess, for fear that she would be eaten by the Japanese.

“He was a real dog lover, so that must have been heartbreaking,” says Jack’s son Andrew, who has lovingly researched his dad’s wartime story.

The prisoners were transported to Shinagawa and forced into hard labour, mining iron ore.

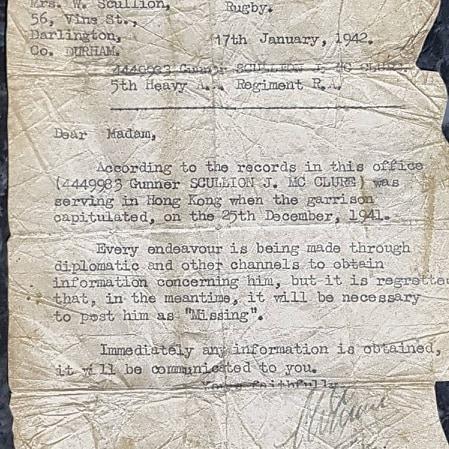

Back home in Vine Street, Darlington, Jack’s mother received a letter from the Royal Artillery Records Office, dated January 17, 1942, informing her that 4449983 Gunner Scullion J. McCLure had been in the garrison when it capitulated.

The letter went on: Every endeavour is being made through diplomatic and other channels to obtain information concerning him but it is regretted that, in the meantime, it will be necessary to post him as “Missing”.

A month later, with his family still not knowing whether he was alive, Jack broke a leg in a rock fall at the mine. Bandaged up with primitive wood splints, he was sent back to work, unloading wagons.

It was October 1942 before a telegram landed at the family home in Darlington, bearing joyful news in four concise words: “Good news. Jack alive.”

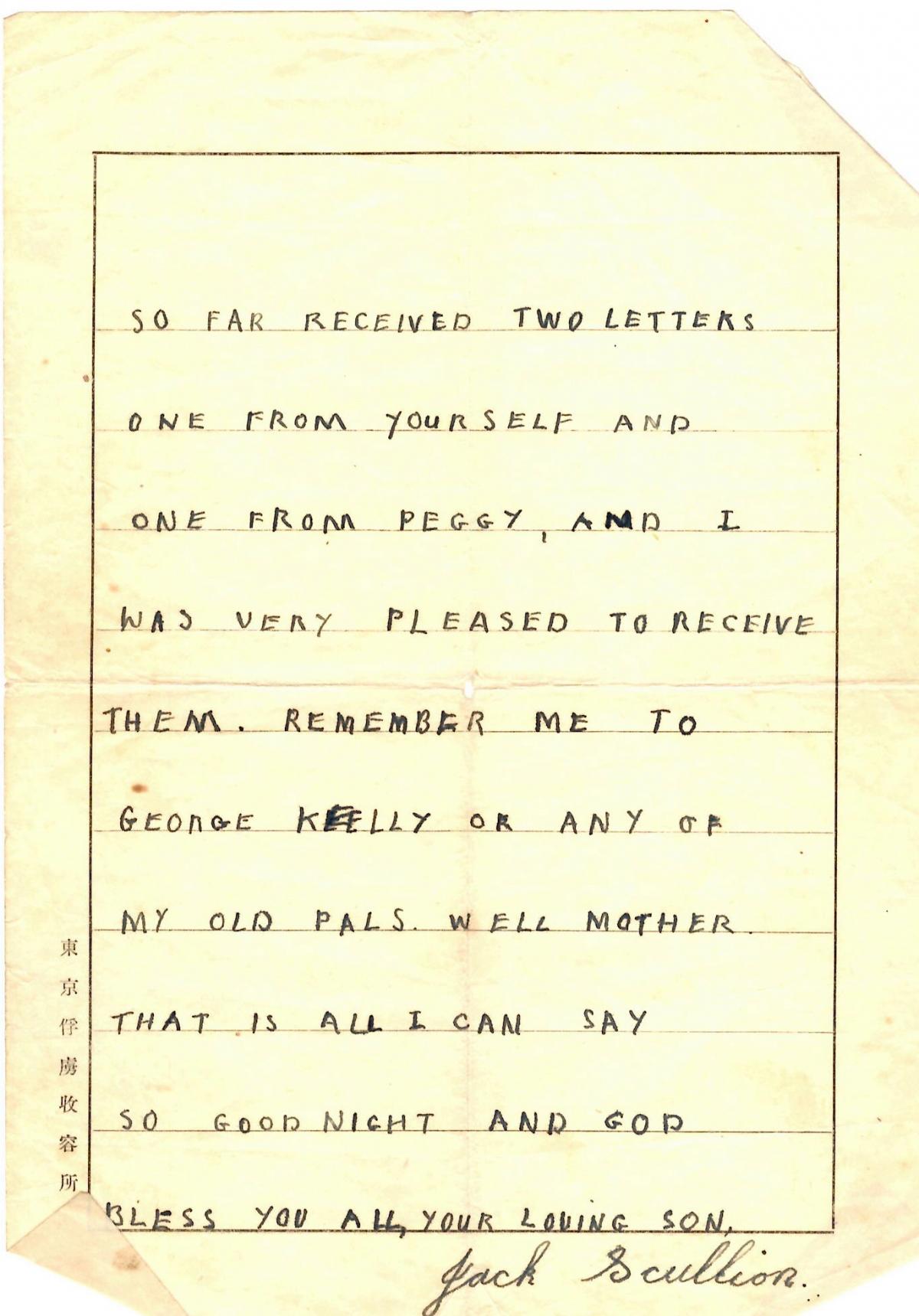

More letters followed, clearly written under duress, with Jack informing his loved ones that he was being treated well, though the reality was that the brutal mistreatment continued.

Although VJ Day had been on August 15, it took the allies until September 24 to liberate Shinagawa. Jack was just one of 26 who survived out of the 286 men who had been taken prisoner from his regiment.

“What they went through was horrific,” says Andrew. “Basic food was horse meat, and, when there was no meat, they were given the entrails made into soup, with rice.

“After VJ Day, the Japanese locked the gates to the camp and left the prisoners to fend for themselves. Rats came in to feed off the dead bodies, and those still alive ate the rats.”

Jack emerged from the camp, having developed a hip injury due to the way his broken leg had been left untreated, and walked with a limp for the rest of his life.

Within a day of the liberation, the men were shipped to Australia because they couldn’t have survived the journey home to England in their emaciated state. Finally, with at least some of his strength restored, Jack was allowed to sail home from Australia, arriving back in Darlington on January 3, 1946.

In recognition of his service to his country, he was presented with a certificate, signed by Alderman Burgess, on behalf of the local council.

Jack seldom talked about his wartime experiences, other than to confide in his brother William, who had served at Dunkirk, and could identify with the horrors of war in a way that those who had stayed behind in England could never truly understand.

Jack found a civvy street job as head storeman at Darlington’s North Road railway workshops, and went on a blind date with a local lass called Mary – better known as Ethel – who worked on the trolley buses from 4.30am in the mornings, and as a tailoress from 2pm in the afternoons. They married and had five children: David, Brian, Michael, Anne and Andrew.

“He suffered terribly, physically and mentally,” recalls Andrew. “He’d talk in his sleep about his mates who’d died, he’d scream out in the night, and he would never have rice cooked in the house. But, despite it all, he also managed to live a full enough life.”

For a start, Jack loved Darlington Football Club, a devotion that Andrew inherited. “He told me I’d have a lifetime of hurt following Quakers – and he was right,” smiles Andrew, now a successful businessman.

Jack’s other sporting passions were fives and threes, and racing greyhounds. There was even one dog – “A For Albert” – that reached the Greyhound Derby final.

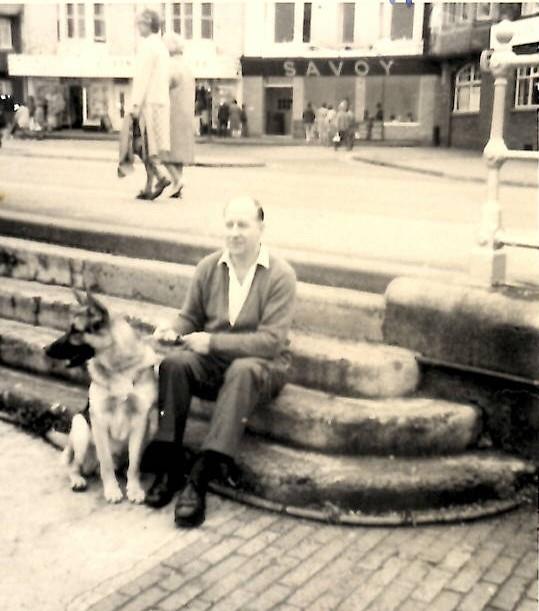

A dog-lover until his last breath, Jack Scullion’s life ended tragically on May 12, 1978, when he was hit by a car while walking his faithful Alsatian, Jason, in Newton Lane. Andrew, just 15 at the time, was one of the first at the scene.

His dad had survived the prolonged torture of life in a Japanese prisoner of war camp, only to lose his life in an instant on a quiet Darlington street.

“I just remember him as a lovely, ordinary fella, who went to hell and back,” says Andrew.

Even now, they still compete annually for the Jack Scullion Memorial Trophy in the Darlington and District Fives and Threes League – but few knew the story behind the name inscribed on the old silver cup.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here