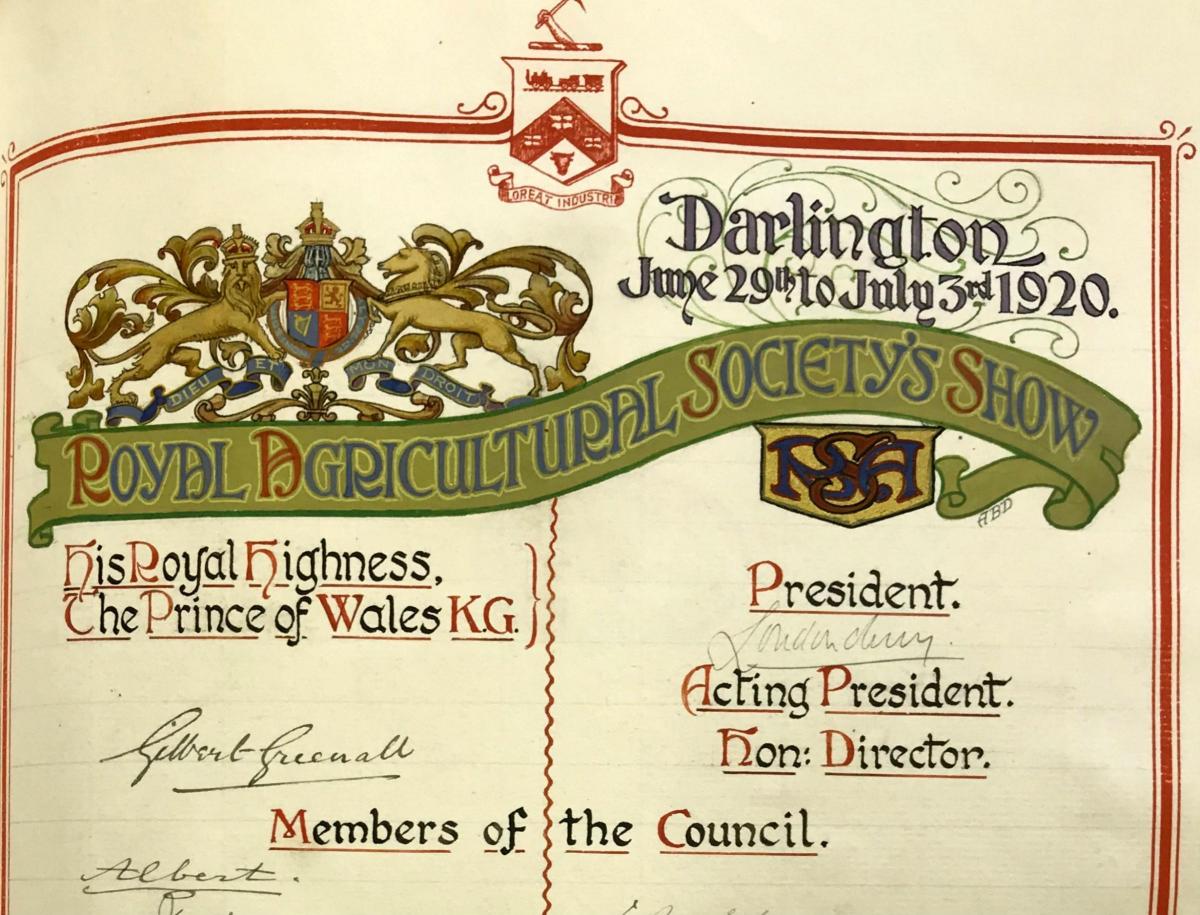

IT is the 100th anniversary of one of the greatest weeks in Darlington’s history: the Royal Agricultural Show was held for the second, and last, time in the town.

Despite a torrential downpour, 182,000 people visited the show, with the Duke of York – the future George VI – the royal guest.

This was the biggest agricultural event anywhere in the country that year, and Hundens, a 130-acre flat farm on the eastern edge of town, had been chosen as the venue because of its proximity to the East Coast Main Line – the North Eastern Railway even built three sidings and a temporary station beside Bank Top for visitors.

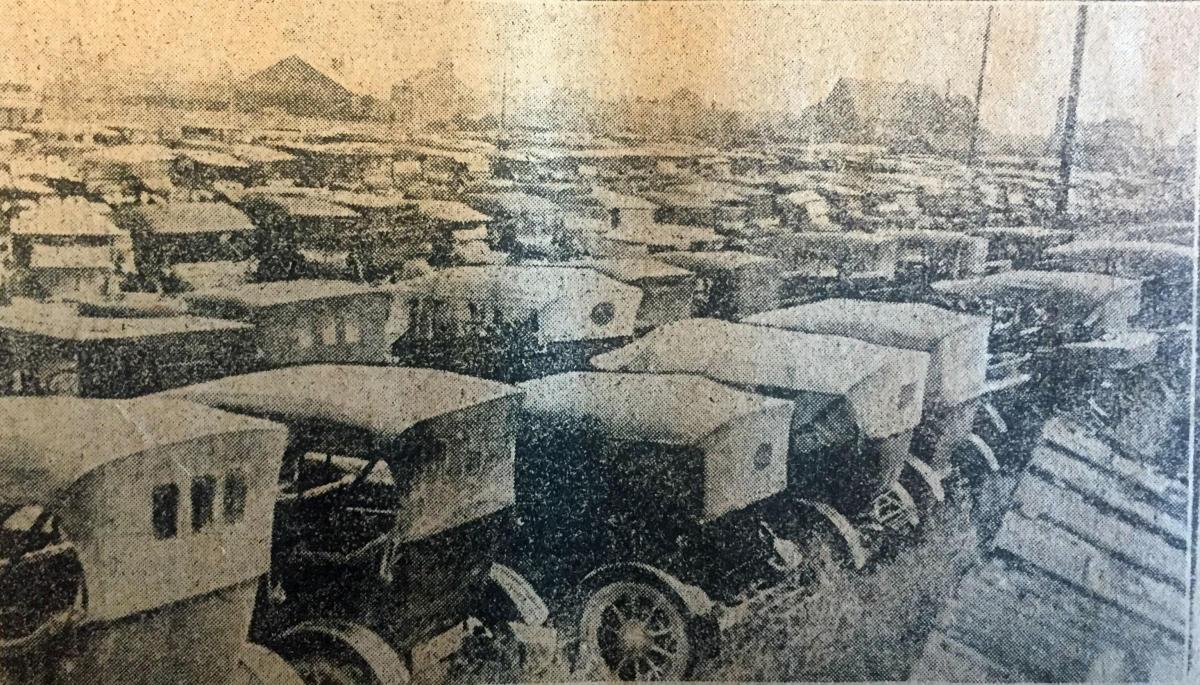

However, anyone who was anyone travelled by motor car. There were “house parties” from Wynyard Hall to Raby Castle, with the local nobility hosting titled people from all over the country.

“One of the outstanding features to Darlington eyes and ears – and scent – was the really amazing motor traffic,” said the Darlington & Stockton Times (D&S Times) afterwards. “In and out and round about it passed in a ceaseless stream from dawn to dark.”

Specially for the motorists, Darlington council had built a new access road which is, to this day, called Hundens Lane.

Constructing the showground had taken about 80 men a year, and they used 10 tons of nails, 70 tons of canvas and more than 1,700 tons of wood.

The central feature was the royal pavilion, a grand five-roomed affair with its own “old court garden”. It had a large oak-panelled dining room decorated with carvings and rich hangings, and the private retiring room had walls of golden brown leather and a panelled wooden frieze. All the furniture was Jacobean oak, and watercolours adorned the walls.

The show opened on June 29, 1920, and that evening the Duke of York arrived at Bank Top Station. He was immediately taken to Wynyard Hall, where he was the guest of the Marquess of Londonderry.

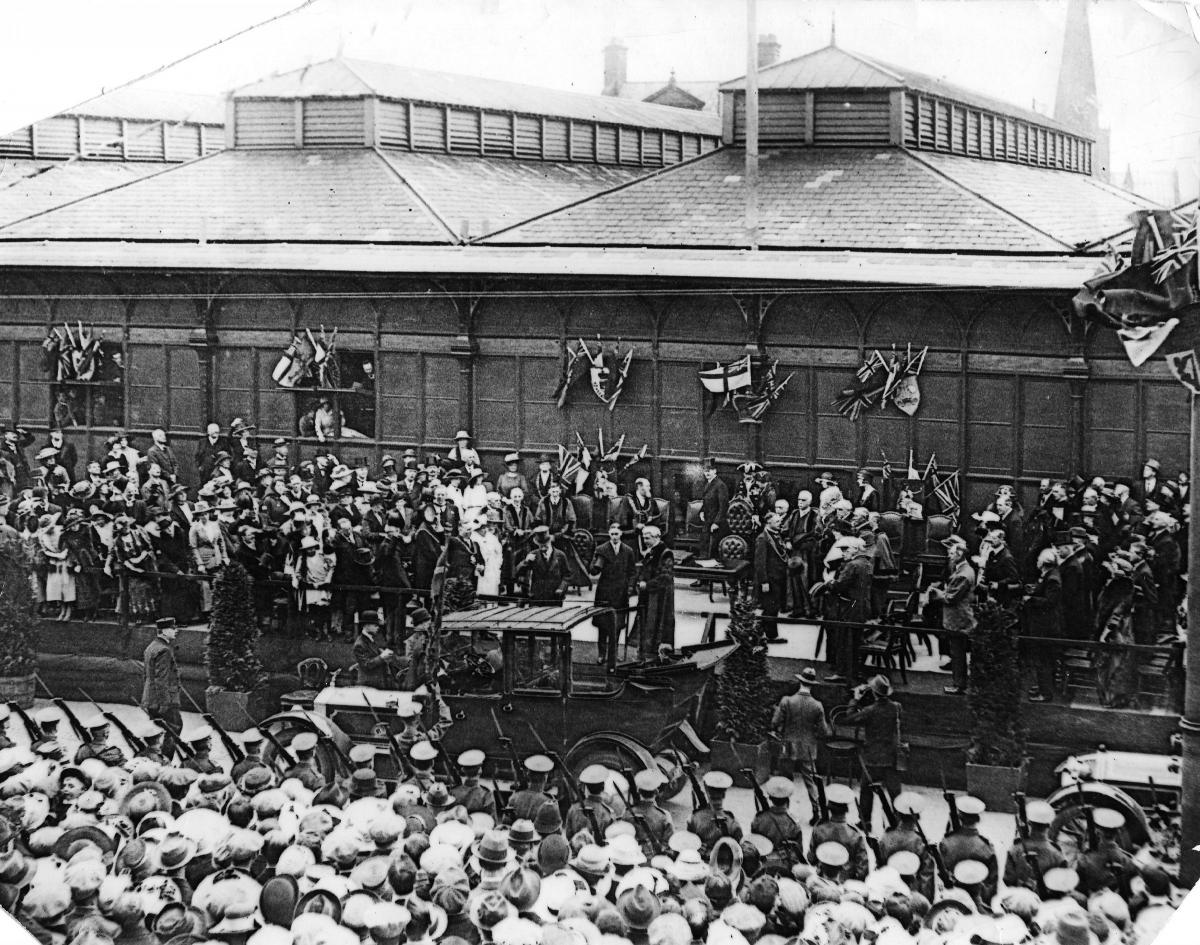

The following morning he motored into Darlington via Haughton-le-Skerne to a civic reception on High Row in the shadow of the town clock.

Although no one in town could have predicted the events of 1936 that catapulted the duke onto the throne as King George VI, people were impressed by the quiet, nervous 24-year-old prince.

“Everybody fell in love with the Duke of York,” said the D&S Times. “He looked such a clean cut unassuming English youth, fresh as a May morning, extremely anxious to avoid any fuss and “jolly glad’ when the brief ceremonial was over.”

Then he motored to the showground up Haughton Road, which was “one solid mass of humanity moving” and all the roads around were choked with “really amazing motor traffic”. Sadly, nine-year-old Joseph William Bee, of St John’s Chapel in Weardale, dashed out from behind a tramcar into the path of a motor, and was instantly killed.

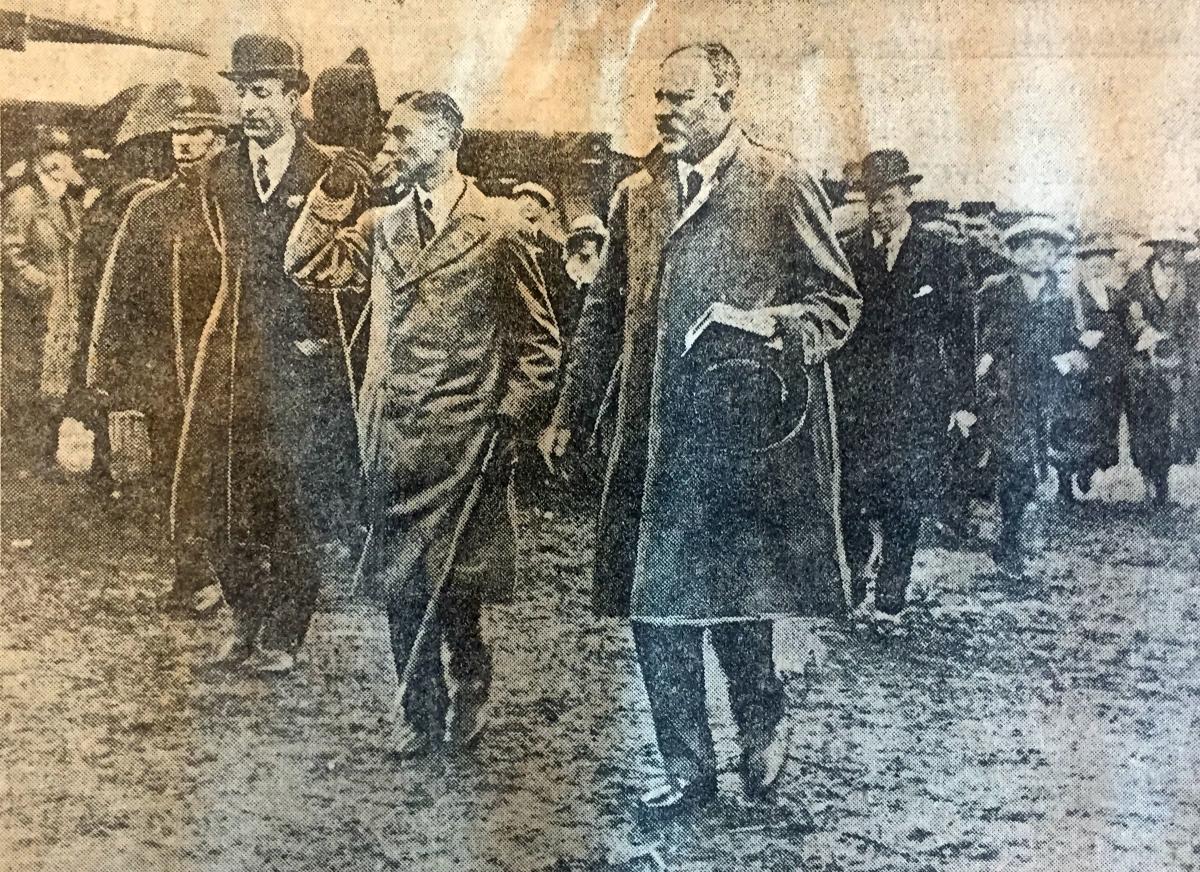

Once at the showfield, the duke spent a few moments enjoying his pavilion, before launching himself into a tour of the stands, on which more than 500 firms exhibited 5,000 new-fangled pieces of equipment.

“The display of motor tractors was the finest ever gathered altogether in the country,” enthused the D&S.

“The farmer who expressed the opinion that the day was not far distant when he would be able to sit at home and allow the farm to be run by mechanical means was perhaps a little ahead of his time”. But not by much, concluded the paper having seen the array of Twenties’ technology.

The Northern Echo noted how electricity, petrol and paraffin were ousting steam as the favoured motive power for all the new machinery, and it was particularly taken by Stand 184 where a Suffolk company was exhibiting a 12mph electric vehicle that it hoped would became a council refuse collector. “This machine will load up to two-and-a-half tons, and will run 40 to 45 miles on a single charge of electricity, and running continuously for six days, will average 30 shillings for power,” said the Echo. Will such technology ever catch on?

The third day of the show was subject to a “pitiless downpour” and yet still 56,000 people visited, with the duke braving the elements until lunchtime.

On the final fourth day, the downpour became torrential, and Hundens was turned into Glastonbury. All the stunning Twenties’ technology was bogged down and unmoveable, and it took six weeks for the pavilion to be extricated from the Hundens quagmire and despatched to Derby where the 1921 show was to be held - the workmen usually reckoned on this operation taking three weeks.

Darlington had previously hosted the Royal Agricultural Society’s annual show in 1895, at the Pease estate of Hummersknott, which had been attended by 100,000 people. Nearly double that number attended the 1920 show which was all the more important because, with the memory of the cataclysmic First World War beginning to recede, the Darlington show was all about agriculture launching itself into a new era.

Darlington was adjudged to have put on a really good show, a part from in the one element that was beyond human control: the weather.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel