AT the funeral of young Bishop Auckland solicitor George Maw, the horse on which he was riding when he had his fatal collision with a lemonade wagon took pride of place.

It was, said The Northern Echo, “a pathetic incident”. “The poor creature walked rather lame, and had a crape or black cloth under the saddle,” said the Echo.

Mr Maw crammed much into his 37 years. As a 20-year-old, we believe he had been flogged during a brief sentence in Durham Gaol. It was such a severe beating that questions were asked about it in the House of Commons, but Mr Maw recovered to qualify as a solicitor and to represent many underdogs – including, four years before his death, two “travelling gipsies” who were involved in a fatal row over hedgerow champagne with a lemonade manufacturer.

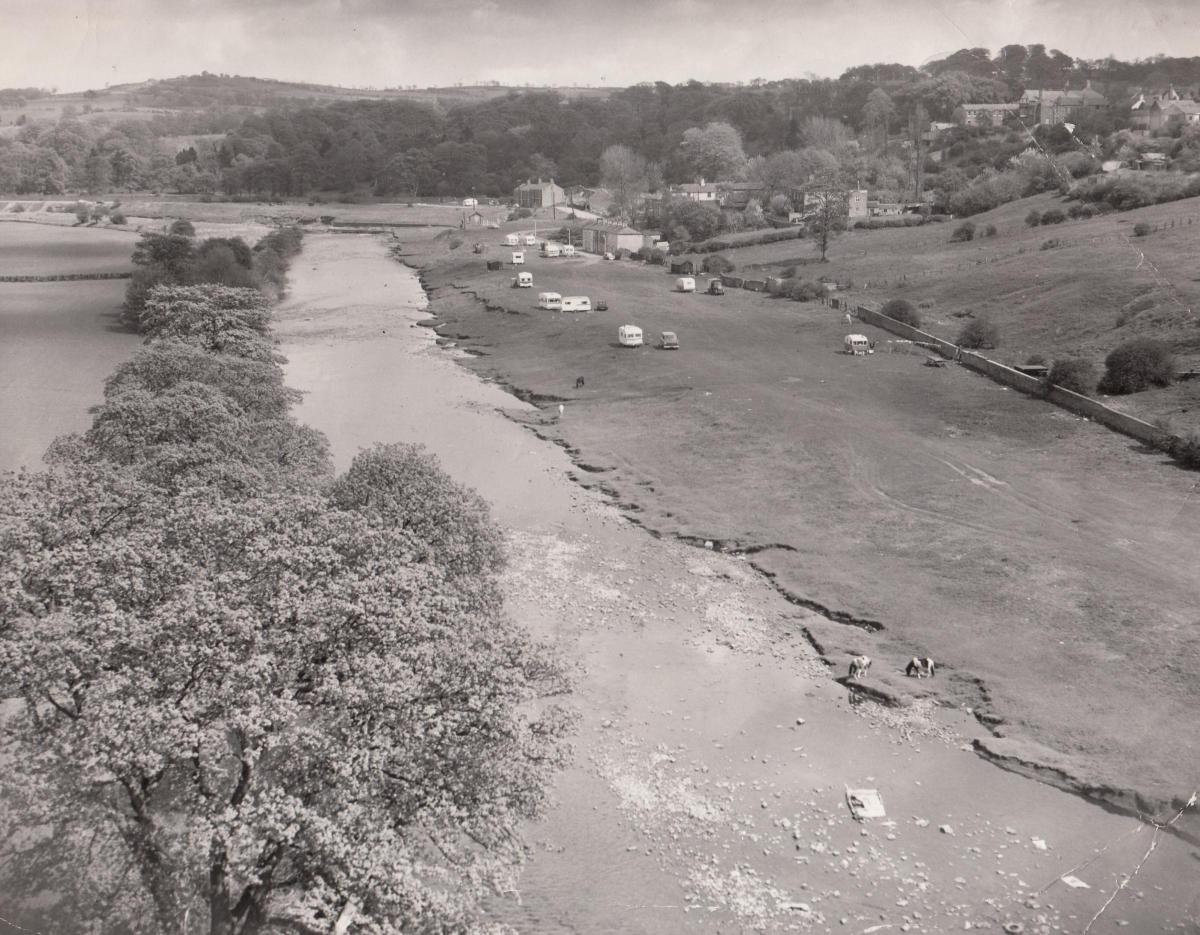

Mr Maw’s father, also George, owned a tannery in Bishop Auckland and lived in Wear Chare, the steep bank which leads from the Market Place down to the Batts, the broad riverbank. George Snr’s tannery employed about 30 men in the 1850s in the Chare. He owned property and was reputedly a friend to gipsies – perhaps this explains why even into the 1970s the Batts was a place where the travelling community rested their caravans.

George Jnr was born in 1850 and attended Durham Grammar School. In 1870, he seems to have stood for election to the Bishop Auckland Board of Health – the town council. The Northern Echo reported how George Maw Jnr was unsuccessful, although its main interest was the exciting battle at the top of the poll where teetotaller Joseph Lingford went head-to-head with publican George Moore. The publican, noted the Echo, beat the teetotaller by 87 votes.

A month after the election, there was a curious incident in Newgate Street. George Maw Jnr, returning from a foxhunt, spotted builder William Edgar in the street. Mr Edgar was a member of the Board of Health.

Mr Maw rode his horse around him three times, forcing the animal into Mr Edgar’s chest so that Mr Edgar had to flee into a shop.

In court, Mr Maw represented himself and said he was merely riding around Mr Edgar to establish his identity. Magistrates, though, unanimously found him guilty of “an assault of a gross nature which could not be overlooked” and sentenced him to 14 days hard labour in Durham.

He refused to attend church and was put for three days in solitary confinement. He only picked 2lbs of oakum – teasing fibres out of old rope to make new rope – a day rather than the expected 4lbs, and then he punched a warder and a fellow prisoner. For this, he was lashed 24 times on the back.

The people of Bishop Auckland were outraged. They crammed the town hall for a public meeting and passed a resolution saying that such treatment was “inhuman”, especially as he was suffering from “delirium tremens” which today we would associate with an alcoholic’s withdrawal symptoms. It was said that having completed his sentence just two days after the flogging, Mr Maw was “discharged in a most deplorable condition, both in body and mind”.

The townspeople asked their MP, Joseph Whitwell Pease, to take the case to the Home Secretary, Henry Bruce. Mr Pease did, and although nothing came of it, it was generally considered, locally at least, that the state of a prisoner’s mind should have been considered before such a brutal sentence was administered.

Mr Maw recovered, qualified as a solicitor and began working in 1872. “His forensic achievements were numerous and, in not a few instances, were brilliant,” said the Echo. “For 15 years, there was not a civil or criminal case of note in the Auckland district in which he was not professionally engaged. He was retained in several cases of wilful murder and took a deep professional pleasure in helping his clients to the easiest way out of their difficulties.”

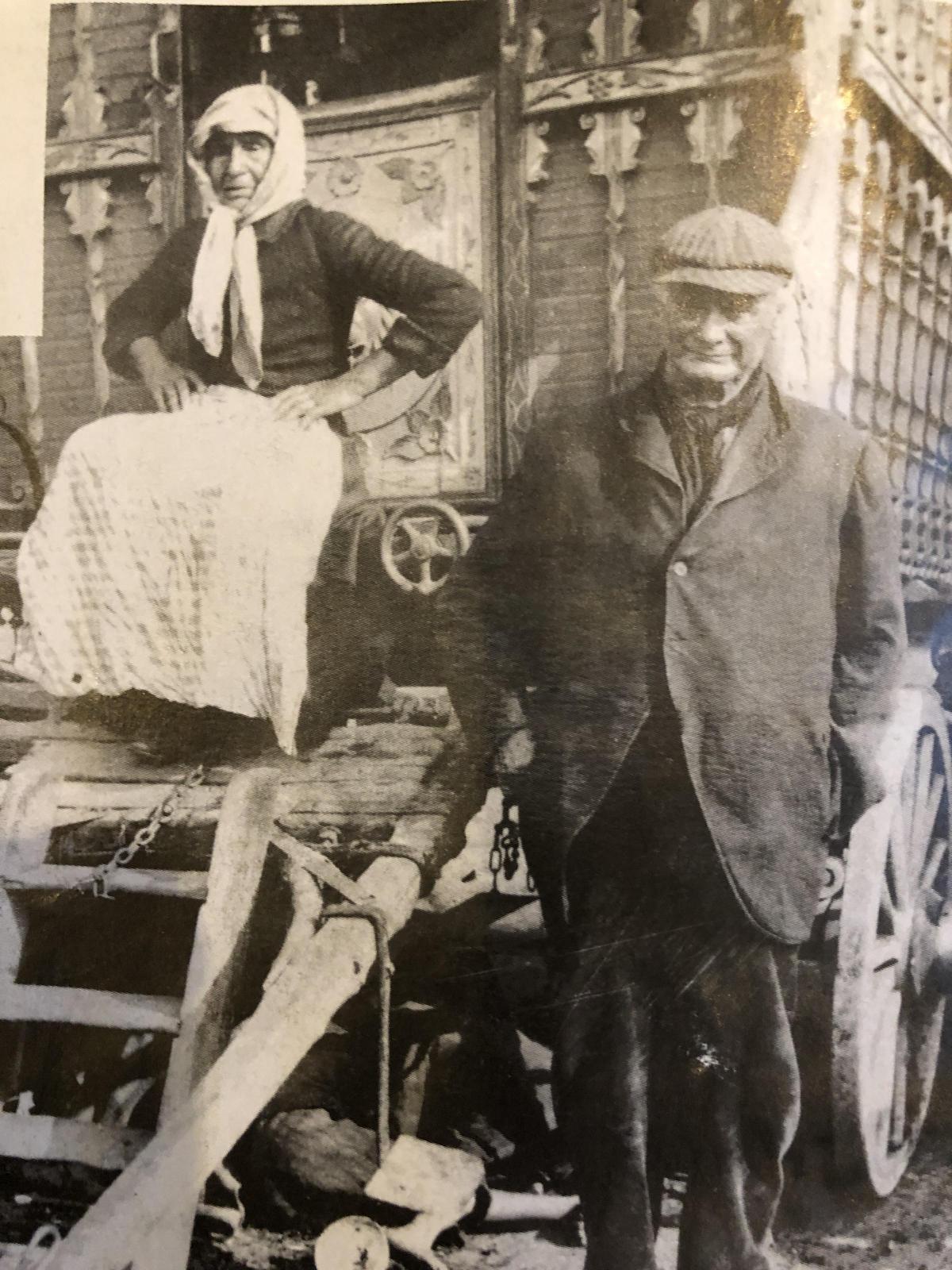

One of the most curious of those cases occurred in 1883 when “travelling gipsy” Christopher Smith was charged with assaulting Joseph Thompson, who worked for his family’s lemonade firm.

It was said that Christopher’s wife and daughter, Patience and Charlotte, had invented a “hedgerow champagne” which had eaten into the local soft drinks market to such an extent that the lemonade manufacturers wanted them driven out of town.

And so, near Pollards Inn on Etherley Lane, there was a collision between Christopher’s stationery cart and one driven by Mr Thompson. The prosecutor made it sound like the gipsies had pounced on Mr Thompson and gave him a thrashing with “an iron hand”.

“Mr Maw, in defence, pleaded for justice for his clients,” said the North-Eastern Daily Gazette, “who, although they were gipsies, were Englishmen and would, he knew, receive at the hands of the magistrates the fullest justice. When they heard the story of his witnesses, they would have a different impression of the affair.”

The witnesses established that Mr Thompson had been drinking whisky and had driven so furiously at the cart that a woman and child inside it were thrown out. He had then charged the vehicle so violently that the wheels became entangled.

It was so persuasive that magistrates discharged one of the gipsies and fined Christopher 6d.

Mr Maw told the court that the child thrown from the vehicle was “seriously ill”. It is believed that the child was Christopher’s daughter and that she subsequently died from her injuries.

Christopher and his family came from a long line of well known gipsies and were often to be found in County Durham. However, after the case, they left Bishop Auckland for Dundee where the womenfolk returned to fortune telling rather than brewing up hedgerow champagne – although the secret recipe still exists.

Four years after the case, Mr Maw was returning to Bishop on his horse down South Road after a distressing day’s hunting – he was “deeply grieved by the loss of a favourite pointer on the railway at Barnard Castle”.

At 8.15pm, near the station, outside the Wear Valley Hotel, he “came into violent contact with the two-horse mineral water van belonging to Mr Robert Thompson” – the head of the family firm of lemonade makers.

Mr Maw staggered into the hotel. “From the knee to the groin, the flesh was literally torn from the bone, and the haemorrhage was excessive,” said the Echo. “It was thought at one time that amputation must be performed, but that idea was not carried out. He partook of beef tea, milk and such like nutriment, but was too feeble to enter into conversation.” He died two days later.

An inquest into his death put no blame whatsoever on Mr Thompson, although it recommended that the council should install a powerful lamp on the dark road.

His hugely attended funeral was the following day, his horse with an empty saddle limping behind the hearse as it made the short procession from his home at Henknowle, near the Cabin Gate crossroads, down Gitty Lane (now St Andrew’s Road) to St Andrew’s Church in South Church, where he was laid to rest.

“He was twice married, and was of a genial and generous turn, though determined and unyielding where he thought a display of his forensic strength was necessary to overcome an opponent,” said the Echo.

Not everything in this story is nailed down – old newspapers do not always explain things perfectly (unlike modern ones, of course).

But Josephine Smith-Mands, the great-grand-daughter of Christopher Smith who Mr Maw defended, has been in touch.

“I am very keen to learn more about the Durham side of things,” she says, “as I have been handed down the recipes from Patience and Charlotte. With a little 21st Century magic, I am hoping to do them proud by producing their tonics and "champagnes", which I hope to launch in 2020.

“It would be very special to connect with any relatives of George Maw. I would love to raise a glass of the Hedgerow to them, and I am hoping to name a mixer "Gentleman George" in his honour.”

George left a widow and a son. If you have any information about this amazing story, please email chris.lloyd@nne.co.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel