THE terrible scenes at Notre Dame in Paris of a skeletal ribcage of timber roof supports being picked clean by twisting, spiralling orange flames were a painful reminder of similarly destructive blazes at York Minster.

There have been several over the centuries, with events of July 9, 1984, still seared onto living memories. A lightning strike had a third of the roof ablaze within half-an-hour, the timbers quickly stripped bare and then deliberately brought down by the firemen’s hoses in a bid to stop the flames spreading.

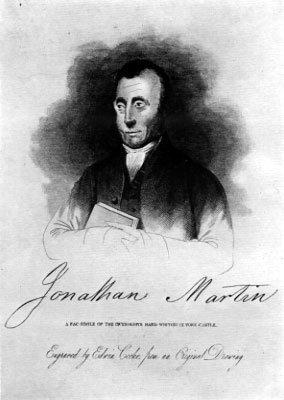

That wasn’t the first fire at the minster. There was a blaze in the south transept in 1753 which was blamed on workmen’s burning coals; there was a major conflagration in the nave roof in 1840 caused by an unattended candle. They were all accidental, but the fire of February 1, 1829, was deliberately set by Jonathan Martin, a tanner who gave his address as Darlington.

He was born near Hexham, was pressganged into the navy, suffering a serious blow on the head during a maritime battle. After six years, he escaped, and found work in a tannery at Norton, near Stockton.

By 1814, he was seeing visions and hearing voices, and was reading messages from God into the noise of thunderstorms. He began a personal crusade against Church of England clergymen who, he believed, led degenerate, extravagant and frivolous lives.

He began hiding in local churches and popping up mid-service to rant at the clergyman in the pulpit until he was “forcibly expelled” by churchwardens. In 1818, his wife informed magistrates that he was planning to “try the faith” of the visiting Bishop of Oxford by pointing a pistol at him in Stockton, and constables carried Jonathan off to an asylum – first in West Auckland but later in Gateshead, where he was kept in chains.

He acquired a piece of stone and ground away the heads of the rivets of his fetters. They snapped, he was free. He slipped out onto the roof, dropped onto a wall and down onto a dungheap and away – he regarded his escape as a God-given miracle.

He reached Darlington, and resumed his career as a tanner, and even began courting a housekeeper in Tubwell Row. In 1825, he wrote an autobiographical pamphlet called The Life of Jonathan Martin, of Darlington, Tanner. He claimed it was "an account of the extraordinary interpositions of divine providence on his behalf", and for three years, he toured the North of England, flogging his story and earning a living - he sold about 14,000 copies of his pamphlet at one shilling a time.

But the visions were coming back, stronger and stronger. A hymn by Charles Wesley was echoing in his head: "Jesu's love the nations fires, Sets the kingdoms in a blaze."

In late 1828, he settled in York at 60 Aldwark. The dreams became more and more lurid until, in one, "a wonderful thick cloud came from the heavens and rested upon the cathedral". Jonathan knew what he had to do.

After Evensong in York Minister on February 1, 1829, Jonathan hid in a pew until the church emptied and the huge doors clanged shut. He used an old razor to cut up velvet and gold tassels from the Bishop's pews into kindling, which he placed beside pages torn from hymnbooks and the wood of the choir stalls. Then he struck his flint - and fled. He knocked out a window and lowered himself on a bell rope.

The blaze was not discovered until early the next morning, by which time the Minster was well alight. At about noon, the huge oak timbers of the roof crashed down on the choir, molten lead pouring through the void in an apocalyptic scene of destruction.

This collapse, though, enabled the firemen to reach the flames and, after a day of toil, they successfully extinguished them. The 14th Century woodwork was lost, as were the 66 choir stalls, the galleries, "the finest organ in England" and its irreplaceable collection of music, the pulpit and the archbishop's throne.

It did not take long to work out the identity of the arsonist.

The clergy had recently received three letters, warning them that if they did not forsake their bottles of wine, downy beds, roast beef, plum puddings and card playing, "your greet Minstairs and churchis will cum rattling down upon your gilty heads!"

One of the letters was signed JM and Jonathan Martin was arrested six days later at the home of a relative near Hexham with candlestubs in his greatcoat pockets, plus fragments of stained glass and pieces of crimson velvet and gold tassels that he had taken as mementoes.

At his trial in York, he admitted setting the fire, and it took the jury seven minutes to conclude, mercifully, that he was "not guilty on the grounds of insanity".

This dismayed the large crowd who had gathered in the hope of a hanging, and Jonathan was carted off to the Criminal Lunatic Asylum, in Lambeth, which was known as Bedlam. There he died on May 26, 1838, proclaiming to the end: "It was not me. . . but my God did it."

From the Darlington & Stockton Times of...

April 26, 1919

HEROES of the war were being commemorated while villains were being dealt with, the D&S Times reported 100 years ago this week.

In crowded Reeth Constitutional Club, local boys who had won the Military Medal were presented with envelopes containing £7 10s collected from the Swaledale public. “Mr JW Moore congratulated the boys on their achievements on the battlefield, as well as on their safe return,” said the D&S.

The recipients were Matthew and James Allinson, of Grinton, and Harold Blenkiron, William Littlefair Moore, and John Wagstaff, all of Reeth.

After the presentation, the floor was cleared for dancing. “Dr Speirs was MC and Mrs Scratcherd (piano) and Mr Scratcherd (violin) and Mr FJ Kendall (violin) kept the company on the move with stirring waltzes and other dances,” said the D&S.

However, in front of Northallerton magistrates, soldier Sydney Cundall, of Yafforth, was charged with bigamy.

Sydney, formerly a North Eastern Railway policeman, had married Hannah Britton in Yafforth church on November 14, 1911.

“Prior to the war, defendant was a good husband,” said the D&S, paraphrasing Hannah’s evidence, “and they had corresponded since he joined the Army. There was a daughter born in January 1914. She did not want to do her husband any harm.” In fact, Hannah said she would happily take him back.

But Ida Florence Martin of Gillingham, in Kent, where Sydney had been stationed, said she had “walked out” with him from August 1915. He had told her he was a widower with his mother looking after his child.

They had married on February 28, 1916, just before he was posted to France, from where he had sent her money, including 2s 4d a week from for “her child” – does that imply he was not the father?

Northallerton magistrates forwarded the case to the assizes for sentence, but Sydney’s trusting father-in-law, Mr Britton, provided surety for £25 which enabled him to be “set at liberty”.

Meanwhile, the vicar of Sowerby, the Reverend William Coombs, had married Miss Elsie Hopkins, of Malton, who was a member of the Teesside family of industrialists.

Two days before the wedding, a large company assembled in the school to make presentations to the vicar who had been in the village for a year. “The gifts consisted of a handsome silver Queen Anne tea and coffee service given by the general body of parishioners, a silver cake dish to match from the choir, and a silver-mounted paper knife from the Church Lads’ Brigade,” said the D&S. The pop-up toaster obviously hadn’t been invented.

Of the wedding, the D&S said: “The bride was attired in a dress of moonlight blue charmeuse, and wore a mole and blue toque with gold veil, as well as a wreath of orange blossom, the gift of Lord and Lady Middleton of Birdsall House.”

Birdsall House, near Malton, has been in the Middleton family since it was built in 1540.

A toque is a classic 1920s brimless hat – and we guess that Elsie’s was edged with velvety mole fur. We were also surprised by the colour of her moonlight blue – but deep blue is the colour most closely associated with the Virgin Mary, and we guess the new vicar’s wife was evoking that with her choice. Traditionally brides wore coloured dresses until 1840 when Queen Victoria married in white – to promote the British lace industry – and so set a trend which is largely followed to this day.

May 1, 1869

THE D&S 150 years ago this week was very disappointed at rumours that the wooden footbridge over the Tees at Cotherstone was going to be removed.

“No bridge upon the Tees can be more useful than this one,” said the paper in an angry outburst directed at the landowner, who was presumably Lord Barnard of Raby Castle. “It not only affords facilities to the public living on both sides of the river, but to our summer visitors it is invaluable, as giving access to the charming scenery on the Tees in this locality. To take away this bridge, and not replace it by a better, would be an unjustifiable exercise of the rights of property, and a wanton interference with the public accommodation.”

Quite why or when this timber bridge was built we’ve been unable to ascertain. It survived this threat in 1869 only to succumb to the great flood of 1881. It was then replaced by a suspension bridge which gave way on Good Friday 1929 under the weight of a football crowd – about 40 people who had been to watch Cotherstone play Mickleton on the Durham side were plunged into the river as they returned home and one, Sarah Nattrass, 31, died of her injuries.

The current footbridge was built in 1932.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here