UNDER the headline “patients must be patient”, The Northern Echo’s front page of July 5, 1948, devoted two paragraphs to “Britain’s new National Health Service which starts today”.

For more than a century, Britain had been discussing how to improve its hotch-potch of health services until the cataclysm of the Second World War presented the opportunity for radical change, but still it only got two paragraphs on the front.

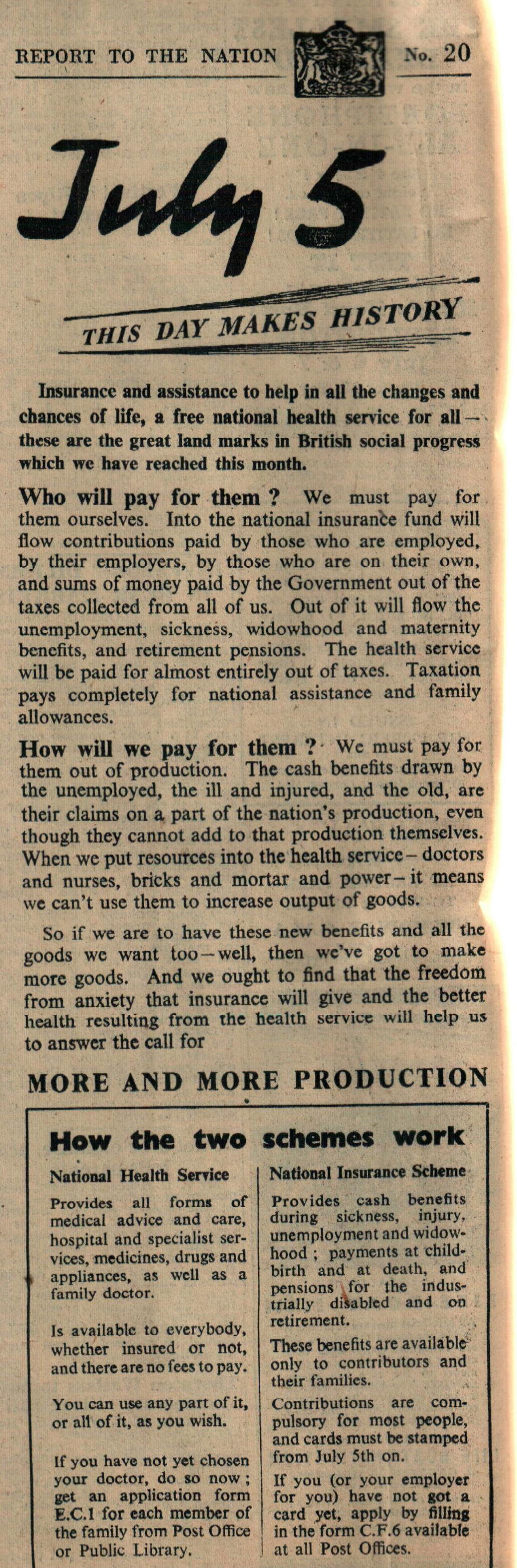

Fortunately, the Government had taken a large advert on the back page proclaiming that “July 5 – this day makes history”, and explaining how the NHS would work and be paid for.

For the first time, hospitals, doctors, nurses, pharmacists, opticians and dentists would come together to offer a service that was free for everyone at the point of delivery and which was financed entirely out of taxation, meaning each person paid what they could afford.

The NHS nationalised existing health services and hospitals, many of which were on the verge of bankruptcy having been randomly run by charities, volunteers and councils. Over night, the NHS became the third largest employer in the country with 364,000 staff, including 9,000 doctors, 149,000 nurses and midwives, and 2,751 hospitals.

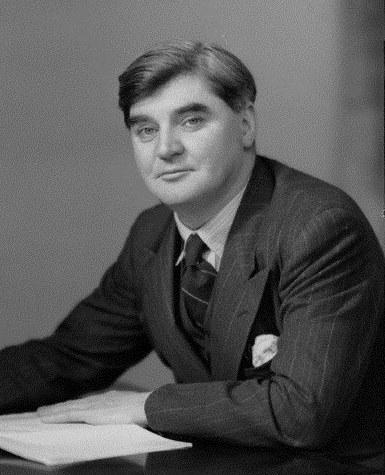

Its architect was the Labour minister for health, Aneurin Bevan, who had shown immense skill in bringing all the institutions together and keeping all the vested interests happy. In February 1948, the doctors’ union, the British Medical Association, had voted by eight to one to boycott the NHS, and even on July 5, the Echo was reporting that dentists in 52 areas, including West Hartlepool, were refusing to join in.

Despite Bevan’s left-wing instincts, the NHS was a compromise. It didn’t have the directly-elected control that the socialists dreamed of – instead it had 14 regional boards – and the top doctors were allowed to keep lucratively treating private patients.

The NHS was, though, immediately hugely popular with ordinary people: by the first day, 94 per cent of the 50m population had signed up for it.

The Echo on July 5, 1948, was more interested in the other great, but more controversial, reform that came into effect that day – the extension of National Insurance so that it paid unemployment, sickness and child benefits. It worried that although this had the potential to bring “great benefit to the nation” it might also cause a “thriftless reliance” on the state.

Therefore its coverage of the first day of the NHS was just those two paragraphs on the front. They consisted of a statement from the Ministry of Health appealing for calm.

“The public must remember that, locally, this is a new adventure in the hands largely of new organisations and bodies,” it said. “Everything cannot start without a hitch at a given hour. People can help enormously by not rushing the new services.”

Just like A&E today on a winter weekend. Indeed, within four years, the new NHS was so short of money that a one shilling charge was introduced for prescriptions and a £1 flat rate for dental treatment.

So from day one, the NHS was adored but it was already exhibiting symptoms of the funding difficulties that have typefied its later years.

Tell us your experience of the NHS

Tell us your experience of the NHS. Did it save your life or that of a loved one? Tell us about your time in hospital - for good or bad. We'd love to read your views.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel