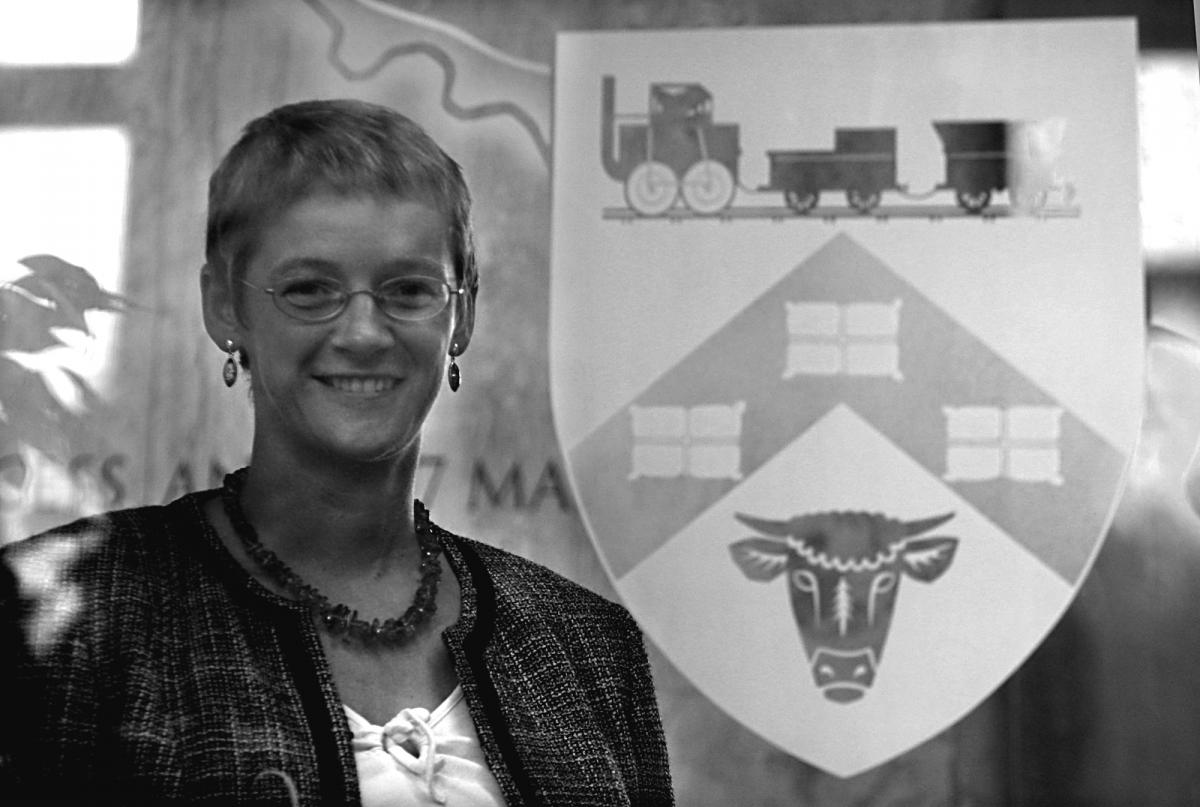

Today, Ada Burns retires after 13 years as Darlington council’s chief executive. From libraries to salaries, she speaks to Chris Lloyd about her legacy

IN April 2005, The Northern Echo introduced the new council chief executive, Ada Burns, to its readers. She, it said, was a mother-of-two who would take charge of an authority with about 4,700 employees and a budget of £140m a year.

The female pronoun – she – feels very important in those early reports. She was the first female chief executive in Darlington’s 150-year history, and in practically all the photographs of her in discussions with other local authority leaders, or of her turning sods on building sites, she is noticeably the only person wearing a skirt.

But now, 13 years on, it is those statistics that seem most shocking. Comparisons are very difficult to draw across the years because the council has lost great responsibilities such as schools, but has gained enormously in others such as public health. But by whatever measure you use, it has shrunk anorexically.

It now has 1,559 full-time employees and an annual budget of £80.64m.

Ms Burns has a figure written on a piece of paper. “In 2010-11, we received £70m from the Government, and in the current year, 2018-19, we will receive £37m,” she says in her soft Irish accent, ending her sentences with a smile for a full-stop.

“If we were a factory and demand fell and our revenues fell, we would stop making as many widgets, we might close a plant.

“But we're not. If a child is at risk of harm, we take that child to a place of safety whether we've got the budget to pay for it or not.”

Ms Burns arrived in Darlington after 18 years working in local authorities in London, having grown up in Antrim.

“In 1978, Ireland was a grim place,” she says, with her bracelets tinkling like gentle windchimes as she speaks. “You couldn't live there without experiencing the impact of the conflict. I was rather closer to a bomb than I would have wanted to be, and as we were evacuated, as we were running away, one of my neighbours lost both his legs, and I was at a party in Belfast where paramilitaries burst in with guns.

“It sounds a bit dramatic, although I suppose it was normal.”

Via university in Kent, she became a graduate trainee with the Greater London Council. Housing and homelessness were her issues, and through tackling them, she became interested in neighbourhood renewal and thus economic development.

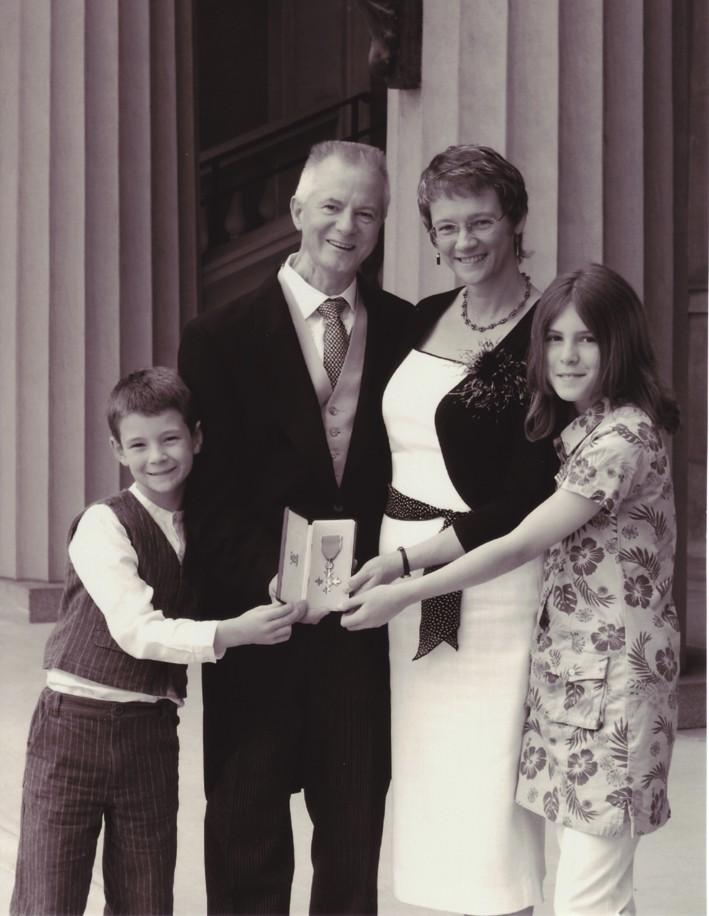

Darlington was advertising for a new chief executive when she was making a quality of life decision. Her children were aged under ten and her husband, Mick Brennan, “had quite serious neck cancer”.

She was plunged into controversy: the proposed closure of Hurworth secondary school, with the £1.5m overspend on the Pedestrian Heart revamp of High Row following hard on the overspend on the Eastern Transport Corridor.

The council reversed out of the Hurworth closure and now Ms Burns rates the three new schools and the new college as among the town’s pre-crash achievements. To address the overspends, she put in place new budgetary procedures and “since we’ve spent hundreds of millions of pounds on capital projects which report quarterly and don't get picked up because it is all fine”.

There were also regeneration projects, like Central Park, Faverdale and Lingfield Point but – boom – the crash of 2008-09 changed the landscape unthinkably.

“We had an emergency Budget straight after the 2010 election and we had an immediate £2m cut,” she says. “The public narrative was of getting the country’s finances back on track and we knew that local government was inevitably going to take a very significant share, because it doesn't enjoy the same emotive profile as nurses or teachers.

“In the first four or five years, the savings were roughly 80 per cent back office so people didn't really notice. There were a few totemic things, like the Arts Centre, but beyond that it was reducing staff, flattening out the management team and changing our processes.

“The 2016 medium term financial plan was almost the reverse, so about 80 per cent of that was public services having to be reduced or cut.”

It was done by looking at each of the 1,300 pieces of legislation that refer to a council’s statutory duties, and working out how to spend the bare minimum on each.

“We did everything we could legally conceivably do and it's pretty ugly,” she says.

Seventy-six per cent of the council’s budget now goes on caring for vulnerable children and adults – there are, for instance, about 220 children in care, each costing up to £70,000-a-year.

She continues: “It is only a very small proportion of the population that has any contact with these services and that’s where the money’s going, but it's the services that most of the population notices like grass cutting, street-cleaning and keeping the parks attractive and the library service that is where the pressure has fallen.”

With dwindling money but rising demand – there were about 170 children in care five years ago – a council can only put up fees, like parking charges, and the local tax.

She says: “I haven't enjoyed much of what I've had to do, and I'm not surprised that the public say ‘I pay more council tax, I get less get less for it, how does that work?’ because they do.”

The other side of the equation is persuading other people to do what the council used to do. The growth of organisations like Darlington Cares, of voluntary Friends groups, and of charities like Age UK, Citizens’ Advice or the 700 Club, which works with the homeless, shows Darlington’s bigger society in operation.

“We had pick, pie and a pint on Friday night and 75 people went litter-picking. There’re people who are visiting the elderly in their homes, there’re those working in parks alongside council staff,” says Ms Burns. “It's just phenomenal. When people talk down the town they are talking down the efforts of hundreds, if not thousands, who do something on a voluntary basis.”

People do talk down the town generally, the council specifically and Ms Burns personally. Much of the focus is her independently-set salary, at £152,227-a-year.

“It is entirely fair to have a debate about senior pay in the public service, and that means in the civil service, in the police and fire, in universities, in schools and academies, in the NHS,” she says, “but there isn’t a debate taking place. There’s an assault.

“Feedback from the public is critical, but social media has created a new platform which isn't feedback – it is abuse and I can't do anything with it.

“Sadly, people in my position have to live with it and have broad shoulders and thick skin. The times I felt it most was when it hit my kids, and it did when they were at school.”

Ever in control, Ms Burns stops her sentence with a smile before she says more than she intends, and then she turns to an upbeat message.

“It maybe is 100, 200, 300 people when everyday there are people right across this town busy volunteering to run the cafe at Age UK, or doing a litter pick, or reading to kids in schools,” she says.

Of all the single issues that has dogged her days, perhaps the closure of Crown Street library is the most contentious. She talks with surprising conviction about how the Dolphin Centre, where the library service would be based, has “huge potential to be at the heart of lifelong learning”. With “imagination and passion”, the 140-year-old library building, she says, can find a new public use.

And of all the continual issues, few have been as long-running as the future of the high street. M&S seems destined to become the latest departure, and she says: “We spent money fighting the retail development at Scotch Corner because we knew it will pose a threat and, sadly, the Secretary of State granted permission for up to 80 stores with 1,000 parking spaces.

“It is really challenging for town centres, but we all have our part to play.

“I would love to see the people of the town talk up the town centre and value what they have. This is a beautiful town, and it frustrates me hugely that not everybody seems to appreciate it. After I retire, I'll still be here shopping, going to the theatre, the Dolly, and the cinema…”

As she bows out, she talks of her legacy being the new schools, jobs and leisure facilities that the council has helped create, but history will judge her tenure as a time of retrenchment.

“The biggest achievement is this council is still here,” she says. “We are not out of the woods yet, but we have a balanced budget until 2021. We do not have major new cuts programmes in the offing. In fact, the reverse is true, we have identified a reinvestment fund to start to restore and address priorities of residents.”

Every set of statistics shows that in 13 years, the council has been drastically trimmed and reshaped. When Ms Burns arrived, Darlington was renowned for its floral displays with its nurseries selling feelgood colour around the country. When the crash came, the colours went, and the days became drab.

But she says: “We've been able to start putting money back into flowers, in partnership with sponsoring businesses, and we are back in Northumbria in Bloom.

“We have weathered the worst of the storm, and you will see the flowers are starting to bloom again.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel