JOHN DARWIN decided that Thursday, March 21, 2002, was the perfect day to disappear.

Debts were crowding in on him and bankruptcy proceedings were only days away.

He finished his nightshift at Holme House Prison, in Stockton, and returned home to No 3, The Cliff, Seaton Carew. When he arrived, his wife, Anne, had already left for her work as a receptionist at the Gilesgate Medical Centre, in Durham City.

WINDSWEPT: The beach in Seaton Carew where John Darwin staged his disappearance

That morning, there were four calls between the Darwins' home number and the medical centre. In one, John told Anne: "This is it ... pick me up later. "

At about 4.30pm, he took his red kayak, the Orca, down to the beach in front of the house.

Anne described John to police as a "competent canoeist" although she said – perhaps to explain his disappearance – that he had never perfected the "eskimo roll" escape manoeuvre.

At about 6pm, Anne drove back from Durham and John returned to the shore. By now it was dark. She met him, as arranged, near the North Gare – the long concrete pier that stretches into the sea to protect the northern entrance of the River Tees. It's a remote spot, hidden away from the main road by a golf fairway and a wind-blown nature reserve renowned for its bird life.

When Anne collected John in her Skoda, he was wearing jeans, a black jacket and a black hat, and he was carrying a rucksack containing his provisions. He gave the canoe a final push back out to sea.

Even though it was an unusually calm day, the high tide waves always crash along the pier and pound down onto the man-made sea defences, making any small craft look extremely flimsy and fragile.

From North Gare, Anne drove him the 40 minutes to Durham railway station to make his getaway. His last words to her were an order that when she reached The Cliff, she should phone the prison and ask to speak to him – as if everything was normal.

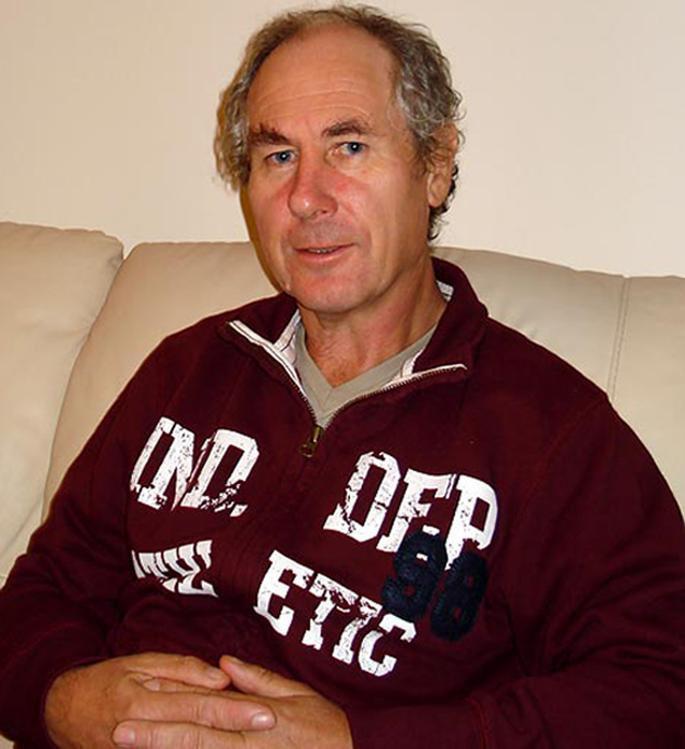

ADJOINING: The houses which belonged to John and Anne Darwin in Seaton Carew

She later told her fraud trial: "I think I cried all the way home when I was driving. I was asked to do something and I didn't know what to do." She knew, though, she had to cover her tracks. She told police that after work, she had gone to the MetroCentre to buy her youngest son, Anthony, an engagement present.

After shopping, she said she had returned to their seven-bedroomed home at 9pm.

John's black Range Rover – with his "cherished" personal number plate D9 JRD – was parked outside, and the phone was ringing.

It was one of those irritating calls that stop just as you reach the receiver. She dialled 1471.

"It was the prison, " she said in her statement. "They said they had tried to contact him as he hadn't turned up for work. I was frantic, and then I noticed that the canoe, which John had left in the hallway, was missing." At about 9.30pm, she reported him missing, sparking a major air-sea search. By the time it was called off on Friday evening, all that had been found was a single paddle at North Gare.

Anne was already in full flow in her role as the grief-stricken widow. Her elder son Mark arrived from London the next morning.

"She flung her arms around me. She said: "He's gone, I think. I have lost him,"" Mark said in evidence. "She wouldn't stop crying for ages." Mark, an international property advisor who is three years older than his brother, then had to break the news to Anthony in Canada.

"I dialled the number but I couldn't speak to him. I had to hand the phone to my auntie. I couldn't summon up the words to tell him my dad had gone missing. "

SIX weeks later, the canoe was found in pieces at North Gare. Six months after that, Anne reluctantly agreed to release her first press statement through Cleveland Police.

It was the most amazing tissue of lies.

She said: "When he went missing, I stayed up all night. I didn't go to bed for days. It was a nightmare and it is still going on. I feel very much in limbo. I've gone back to work to try and get some normality into my life, but it's just there, 24 hours a day."

She continued: "The view from my window is a daily reminder. This was to be the house of our dreams and I have just got to look out and not dwell on the tragedy. John loved the sea, from being a small boy he loved the beach.

"People die, have a funeral, they have a headstone, there is something to mark the fact they existed on this earth. But without a body, I don't know how we can mark John's life.

"All I want is to bury his body. It would enable me to move on. "

She concluded with words that, in hindsight, reveal much: "I have no reason to think he would have left and stage-managed this. I think John has met with an unfortunate accident in the sea and has died. That's the only way I have been able to cope with it."

The September 2002 statement was compiled by Cleveland Police press officer Charlie Westberg.

"I spent up to an hour at her house, " he recalled. "She was very quiet and very quietly spoken. She did not want to say much and had to be prompted to say anything.

"I thought it was very sad that there she was in this very big Victorian house looking out of the window and looking out to sea where her husband disappeared. " But Mr Westberg felt something was not right.

"I thought it was strange that she did not have a photograph of her husband.

"She just said something like: "We are not ones for photographs". Now we know why – he was probably next door the whole time."

HAVING been dropped off by his wife at Durham station on the night that he had "drowned", John Darwin told police that he travelled to the Lake District where he lived under canvas.

It is thought, though, that he merely stayed in one of the couple's unoccupied houses.

He phoned Anne regularly to find out if the coast was clear and his grieving sons had left for their homes in the south of England.

"He was getting desperate, " Anne later told police. "He phoned me and gave me directions to where he was. I didn't want to go and pick him up, but I couldn't leave him. At one point, he was literally crying on the telephone."

She drove to the Whitehaven area of Cumbria to pick him up, although she told her trial that she did not recognise him at first because he had grown a beard, was wearing different clothes, was walking with a limp and was using a walking stick.

With such a disguise, John was back at The Cliff – possibly as soon as a fortnight, definitely no longer than a month, after his disappearance.

He took up residence in No 4, the large seafront property next door to Anne's house. The couple had bought the two properties in December 2000, apparently unaware that a secret passageway hidden behind an attic wardrobe connected them.

Now John would live with Anne in No 3 and he would scurry back to No 4 whenever anyone visited his grieving widow. He concreted over the floorboards in the secret passage so their creaking didn't give him away as he did his scurrying.

He didn't hide away, though, regularly limping down to the beach, and joining Seaton Carew library on April 22, 2002 – only a month and a day after he was lost at sea.

He was spending his time constructing a new identity, scouring graveyards and local newspapers, until he chanced upon the name of John Jones – a name he first used when he registered with the library and began borrowing books.

The real John Jones was born five months before Darwin, on March 27, 1950, at his gran's home in Sunderland, the son of river worker Alfred John Jones and his wife, Lily. He died after only five weeks from enteritis at the city's Hospital for Infectious Diseases, and was buried on May 3, 1950.

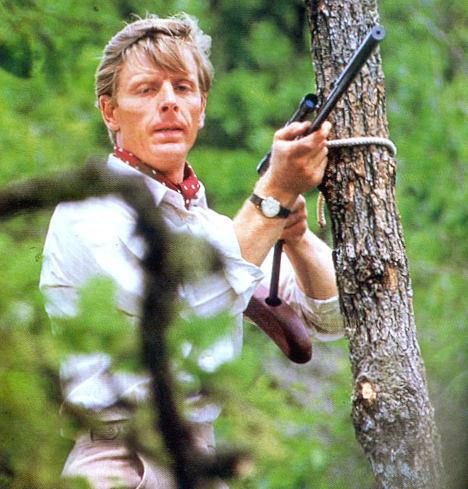

Darwin's stealing of the identity is similar to the plot of Frederick Forsyth's novel, The Day of the Jackal, which was turned into a film starring Edward Fox. In it, Fox trawls graveyards looking for the headstone of a baby boy whose name becomes the basis of a false identity.

Darwin used John Jones' name to get a birth certificate.

He then used the birth certificate, accompanied by a black and white photo of himself sporting a long bushy beard – a photograph which a librarian signed to authenticate as he was such a regular customer – to get a passport.

Again, he was astonishingly brazen, even using the couple's home address to get the passport.

Anne was also busy.

Because of mounting debts, she needed to claim on John's pensions and life insurance policies – fortuitously, they had taken out a "fatal accident" policy in December 2001 only four months before John had had his "fatal accident".

DAMAGED: The remains of John Darwin's canoe recovered from the sea

To get the cash, she needed to get the chap who lived next door – her husband – declared dead.

"When a claim is made for life insurance, an insurer will normally require sight of the death certificate. If there is a body, then there will be a death certificate available, " said a spokesman for the Association of British Insurers.

"If a person disappears and nobody is found, an application can be made to a coroner's court to have that person declared dead.

"This application is made automatically if someone has been missing for seven years, but the application can be made sooner than that if there is strong evidence available that the missing person may be dead."

She first approached the Hartlepool Coroner's Office with breathtaking speed on April 9 – less than three weeks after the disappearance.

A few months later, she applied to the Home Secretary under Section 15 of the 1988 Coroners Act for an inquest to be held into the death of her husband, citing the discovery of the battered, empty canoe as the "strong evidence".

There are more than 29,000 inquests held in the UK a year.

In fewer than ten, there is no body. The inquest into the death of John Darwin was one of that bodyless handful when it was held on April 10, 2003, before the coroner of Hartlepool, Malcolm Donnelly.

After a brief hearing, he recorded an open verdict and issued a maritime death certificate which stated Darwin had "probably" died while in a canoe in the sea near Hartlepool.

Anne now had the death certificate. She even began planning a memorial service to commemorate John's life, but this never happened.

She used the death certificate to claim her husband's £25,000 life insurance policy, his £25,000 teacher's pension, his £58,000 Prison Service pension, as well as £4,000 in payouts from the Department of Work and Pensions, and a further £137,000 from a Norwich Union mortgage insurance policy.

The total was £249,000.

How much of this fraud she committed under her own volition, or at least as an equal partner with her husband, was the crux of her trial. She alleged that, throughout, John had the dominant hand, drafting letters on the computer for her to sign.

She said: "Eventually, he made a photocopy of my signature and that was put on the computer at the bottom of the letter. Basically, a letter could be typed and my signature was added to the letter without me knowing."

Still, the money made it into her bank account. She was solvent. The debts were cleared. Also, she still had a dozen east Durham properties and the two seafront residences on The Cliff. All at a time when property values were booming.

A new dream life beckoned, in a hot, exotic foreign country.

It was full steam ahead for the great canoe conspiracy.

- Tomorrow: John was dead and the money was in the bank. A future filled with sun, sea and sand lay before them. Then it all started to unravel.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel