IT was the most public of murders, filmed as it happened by a television news crew and later seen by millions around the world.

Former Consett steelworker Albert Dryden lifted his gun and fired at planning officer Harry Collinson in what was the culmination of a long-running planning wrangle over an illegally-built “underground” bungalow.

Only a short while earlier Mr Collinson had pinpointed a spot where a bulldozer could enter Dryden’s smallholding at Butsfield, near Consett, to demolish the bungalow, as members of the media looked on.

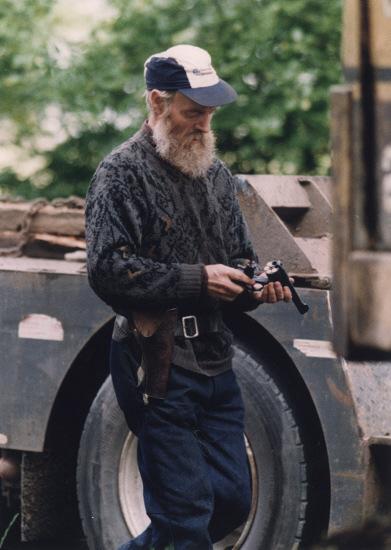

Dryden, meanwhile went to his caravan and picked up a World War One revolver, striding back out to the fence tying the holster to his leg. He drew the weapon on Mr Collinson whose last words were to the TV crew: “can you get a shot of this’’.

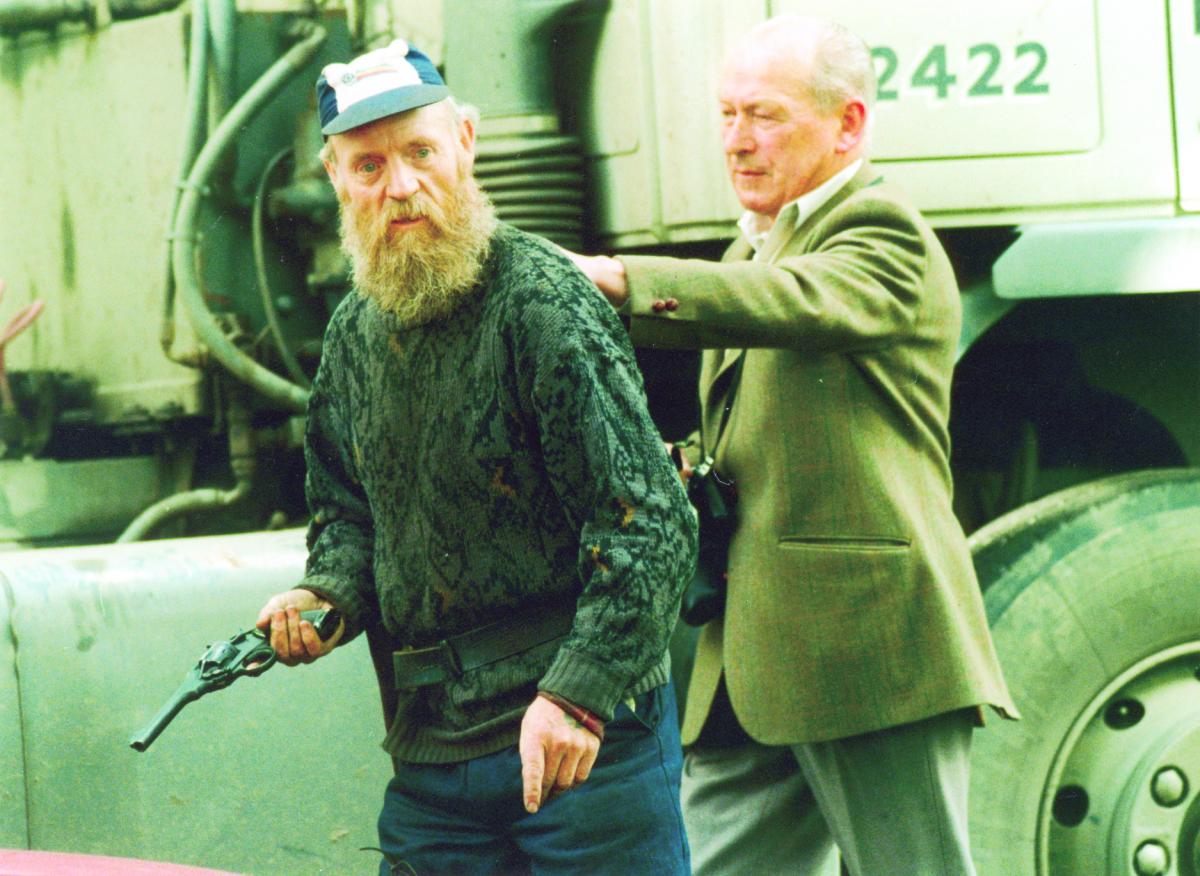

Dryden shot him once and then again as he fell, before firing wildly into the fleeing crowd, hoping to get the council’s solicitor Mike Dunstan.

But instead he hit TV reporter Tony Belmont in the arm and PC Stephen Campbell in the backside.

Following his arrest a short time later, police found an arsenal of weapons in the bungalow.

The fateful morning of Thursday, June 20, 1991 started as a quirky planning row between the eccentric and Derwentside District Council’s planning department.

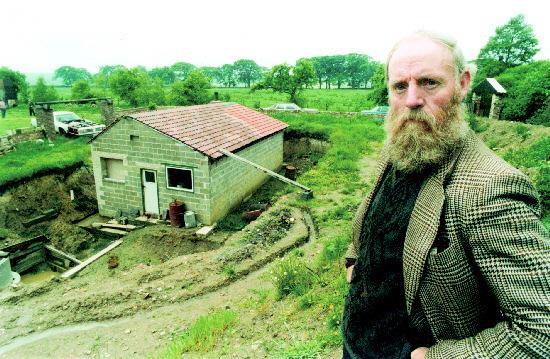

Dryden had ploughed his redundancy money into a one-acre plot of land at Eliza Lane, which he called Maryland Close.

He put up two greenhouses, a shed, parked a caravan on the land and built an archway at the gated entrance.

Then he hired a digger and scooped out more than 2,000 tonnes of earth near the fence with the road and built a partly-sunken bungalow in the resulting hole, forming a screen mound around it.

However, Dryden, did not have planning permission and the council, concerned the bungalow would set a precedent if allowed to stand, took action.

Dryden lost his planning appeal to keep the bungalow and the wrangle dragged on for several months with legal challenges.

The council, wanting to be seen to be acting fairly, announced the date and time of the demolition in advance to the media, even though police voiced their opposition to a public demolition.

Those whose local knowledge went back a decade or two would knew of Dryden’s interest in firearms and home-made rockets, which brought him into conflict with the law in the 1960s.

On the day of the shooting, Dryden had a letter from the Planning Inspectorate, which he had fixed to the gate. He had contacted them saying he wanted to lodge an appeal - in reality he had already exhausted the process - against the refusal of permission for his developments.

It was a pro-forma letter that indicated no action could be taken until the appeal had been heard. Tragically, it gave Dryden the belief that the council was breaking the law even though there were no grounds for an appeal.

The Northern Echo’s photographer Mike Peckett, in his first day on the staff, asked Dryden not to shoot him when the gun was pointed at him. He produced a remarkable series of pictures of the incident that featured on the paper’s front page the following morning.

Durham Police former tactical firearms officer David Blackie, who was called to the scene, questioned in his book Death on a Summer’s Day why he and his colleagues were not consulted about the handling of the demolition, particularly as Dryden was known to be interested in guns.

Dryden’s family demolished the bungalow in April 1992.

Sentencing Dryden at Newcastle Crown Court, Judge Mrs Justice Ebsworth told him he was a dangerous man who had behaved in a “grotesque” way.

Dryden expressed sorrow for his crime in a letter to The Northern Echo in the wake of the 20th anniversary of the murder.

In a rambling account of the planning background his case Dryden concluded: “At the same time I am deeply sorry for what I did 20 years ago.”

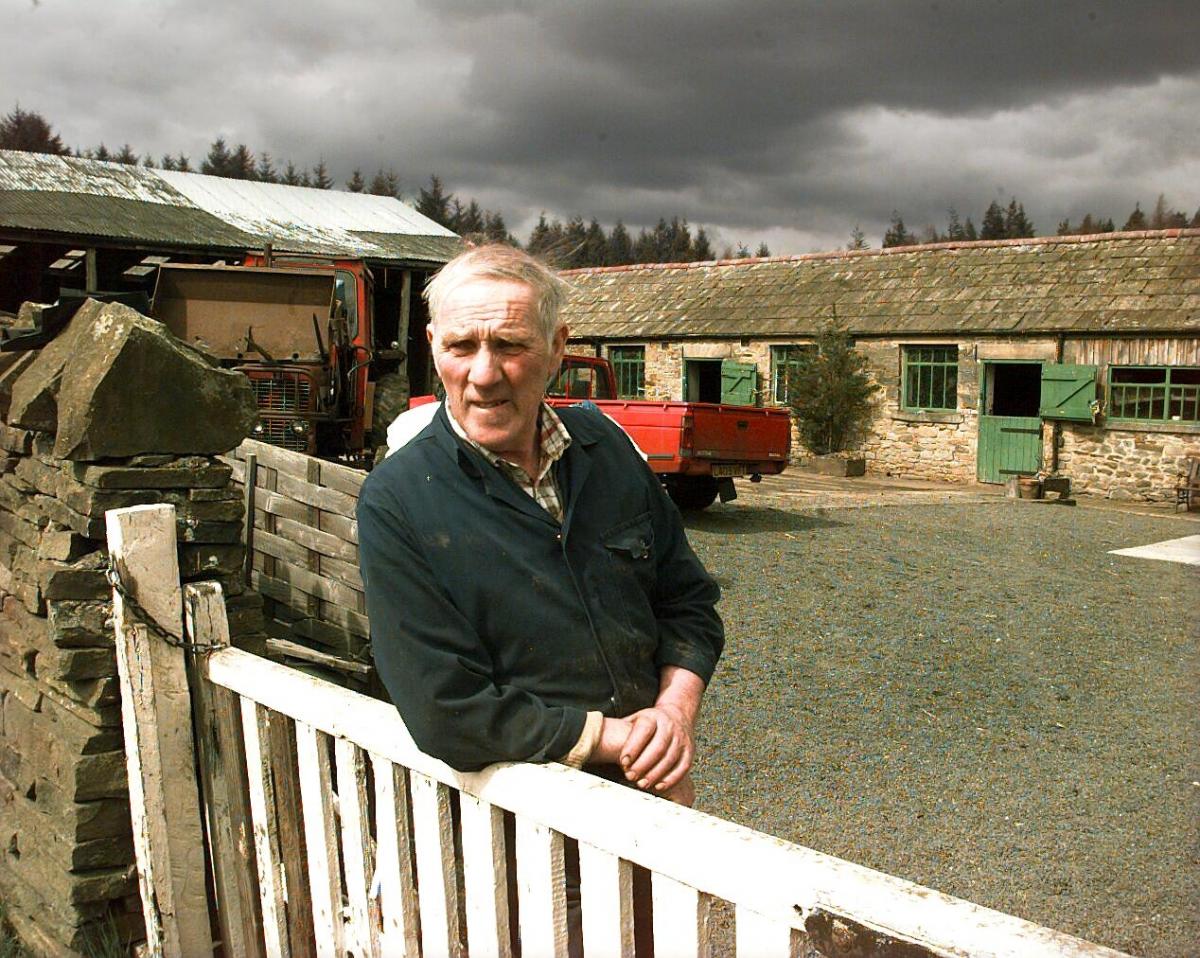

But Collinson’s older brother Roy, rejected the killer’s expression of sorrow as a simple ploy to get out of prison.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here