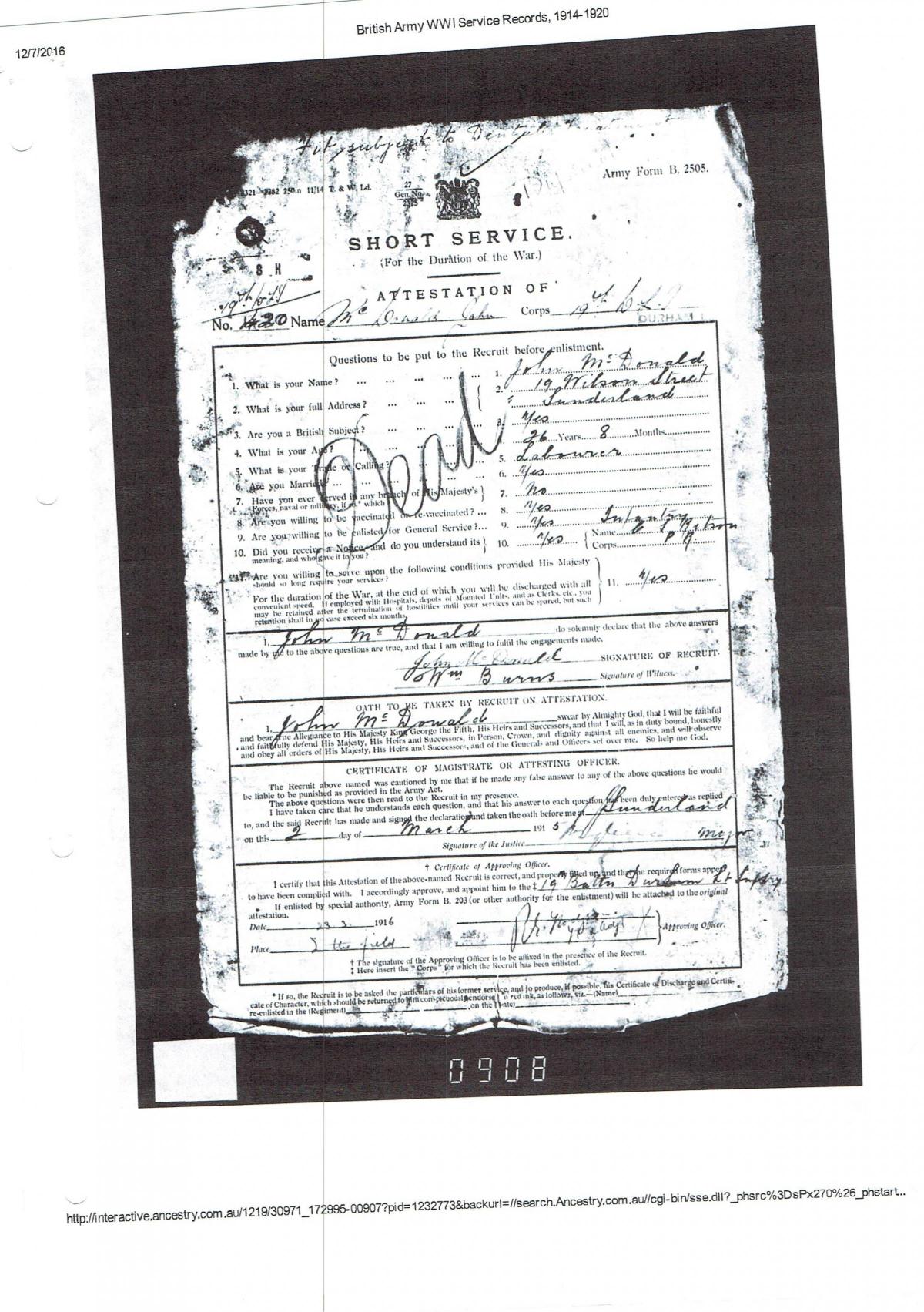

THE previously unknown truth behind the tragic and senseless death of a Durham Light Infantry soldier 100 years ago today has finally solved a life-long mystery.

For the 102-year-old daughter of Lance Corporal John McDonald has just discovered he was executed for cowardice after retreating 20 yards to a reserve trench while under attack.

Florence Johnson spent her life knowing almost nothing of her father and the revelation, although heartbreaking, has allowed her to re-evaluate her relationship with her late mother - whom she resented for “dumping” her in Sunderland with her grandmother.

Her family never spoke of him - given the stigma which would have surrounded his death at the time.

Mrs Johnson (nee McDonald) of Fremantle, Australia, will today commemorates the 100th anniversary of his execution as her family call upon the Government for official confirmation to be sent of his posthumous pardon.

L Cpl McDonald’s granddaughter, Margaret Kermode, who finally learnt the truth during a visit to the North-East last November, said: “We were flabbergasted, because no one ever spoke of him.

“When I told my mother she was very sad, but was relieved to finally hear the truth. She understands now why she was left alone with her grandmother for several years. It all made sense.

“She had always resented her (mother) for leaving her. It has given a peace of mind in the last years of her life. It is such a pity it has taken so long.”

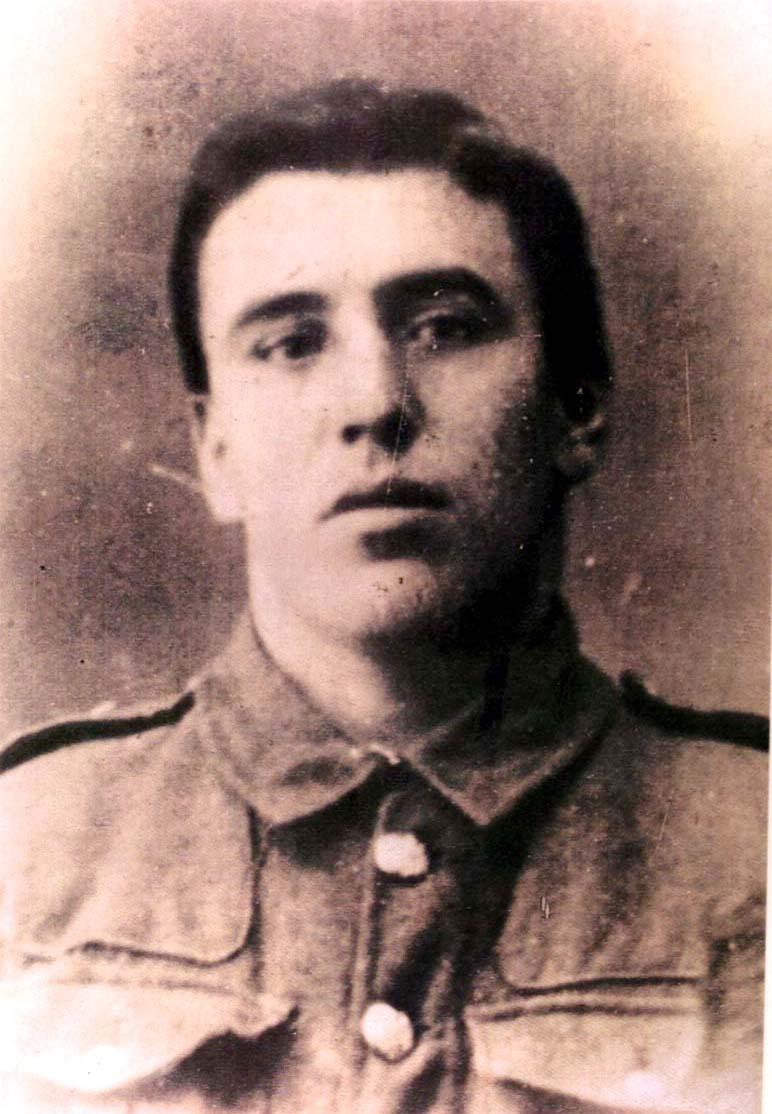

L Cpl McDonald was one of three soldiers from the 19th (Bantam) Battalion DLI who were blindfolded, manacled, tied to a stake and shot in a wood in France on January 18, 1917.

Officers later confirmed the triple execution of the men was carried out to make an example to a 'shaky' battalion.

The 28-year-old father of Sunderland, who was only 5ft 2in, was shot alongside L Cpl Peter Goggins, 21, of Stanley, County Durham and Sergeant Joseph “Will” Stones, 23, of Crook.

They were among 306 soldiers shot for alleged cowardice, who were granted a pardon in August 2008 following The Northern Echo’s Shot at Dawn campaign.

Mrs Kermode said: “I told her the Government had given her father a pardon, but they wouldn’t have known my mum was still alive living on the other side of the world, to let her know. She would love to get written confirmation.”

The discovery was made by cousin Vincent Procter and his wife Joan, of Worthing, who were asked to find information on Hartley Buildings, in Millfield, Sunderland, where Florence lived as a child.

Mr Procter said: “That was the only intent of the visit of her daughter Margaret to Sunderland.

“While Joan was doing research, John McDonald’s name sprung up and on further investigation we were shocked to find he was one of 306 men who were shot at dawn.

“As we discovered this close to the end of their trip and identified the cemetery in France, we were able at the last minute to take them to where he and his two brave comrades were buried.”

Mrs Kermode said: “That was really wonderful. It was beautiful to go there and be only family to go to his grave in 100 years.”

L Cpl McDonald was working with a glassworks and living with his wife Hannah and three young children when he enlisted. He sailed for France in February 1916.

After his death, her mother took her brothers and left Sunderland, later remarrying. She returned eight years later to collect Florence and the family emigrated to Australia.

A Ministry of Defence spokesman said: “After contacting the families who had previously spoken to us about their relatives, we ensured notes for these posthumous pardons were placed alongside the relevant court martial files at the National Archives – that means anyone who researches that individual will see them, not just those who got letters.”

THE triple execution of three Durham Bantams stemmed from a fateful night they came under under heavy mortar fire in thick mist while holding the front line near Arras, in November 1916.

Sgt Joseph Stones and a captain had gone into No Man's Land to find out what was happening.

The captain was shot and the shocked sergeant ran back to his line, shouting "the Hun are upon us".

L Cpl Goggins and L Cpl McDonald retreated 20 yards to a reserve trench to fight off the attack. To the Army, that constituted desertion.

A letter from Private Albert Rochester, who was in detention for complaining about conditions in the trenches, gives a vivid account of the execution.

He wrote: "A crowd of brass hats, the medical officer and three firing parties. Three stakes a few yards apart and a ring of sentries around the woodland to keep the curious away.

"A motor ambulance arrives carrying the doomed men. Manacled and blindfolded, they are helped out and tied up to the stakes.

"Over each man's heart is placed an envelope. At the sign of command, the firing parties, 12 for each, align their rifles on the envelopes.

"The officer in charge holds his stick aloft and, as it falls, 36 bullets usher the souls of three of Kitchener's men to the great unknown.

"As a military prisoner, I helped clear the traces of the triple murder. I took the posts down. I helped carry those bodies towards their last resting place.

"I collected all the blood-soaked straw and burnt it.

"Acting upon instruction, I took the belongings from the dead men's tunics; discarded before being shot.

"A few letters, a pipe, some fags, a photo. I could tell you of the silence of the military police after reading one letter from a little girl to "Dear Daddy", of the blood-stained snow that horrified the French peasants, of the chaplain's confession that braver men he had never met than those three men he prayed with just before the fatal dawn. I could take you to the graves of the murdered."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel