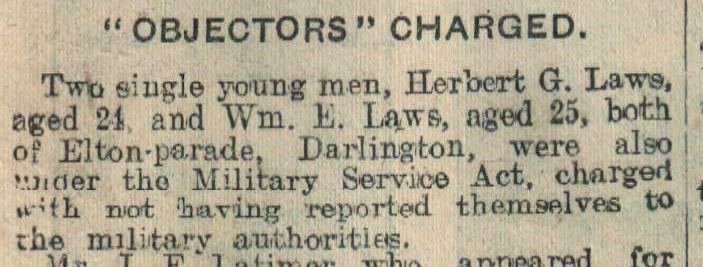

ONE hundred years ago this week, two Darlington brothers were handed over by local magistrates to the military authorities “to deal with as they deemed advisable”.

“This being the first case of the kind that had come before the court, the magistrates were dealing more leniently with them than they would otherwise have done,” reported The Northern Echo.

The “leniency” here was that the brothers – Herbert and William Law – were sent to Richmond Castle, imprisoned in the dungeons for a week and then secretly taken to the Western Front where they were sentenced to be shot at dawn – pour encourager les autres.

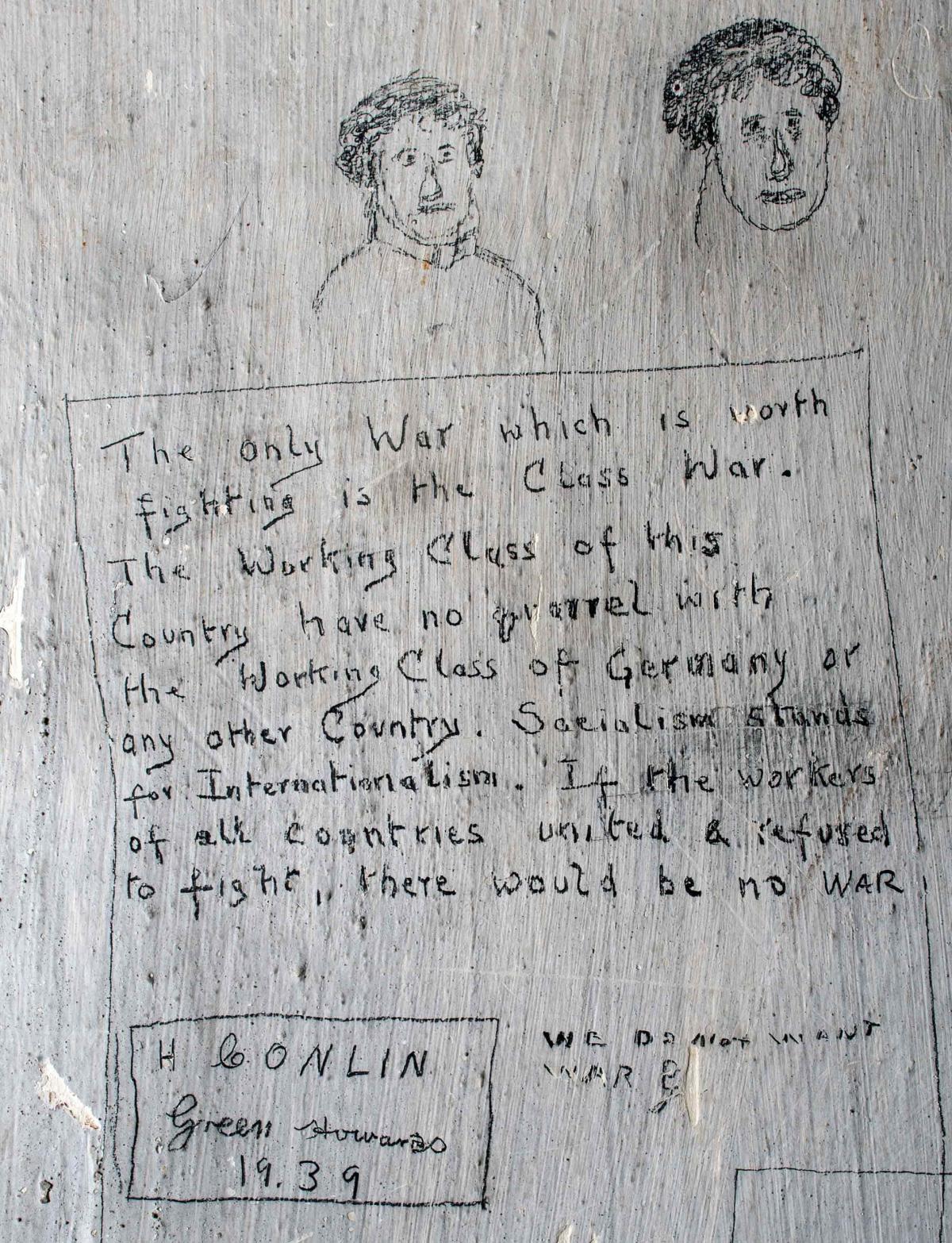

They were two of the Richmond 16 of conscientious objectors whose defiant graffiti on the walls of the damp dungeon is, we learned this week, to be protected.

The “conshees”, as they were dismissively known, were usually religious men – Quakers, Methodists and International Bible Students (now known as Jehovah’s Witnesses) who took the commandment “thou shalt not kill” as unarguable. One of them wrote on the dungeon wall: “You might as well try to dry a floor by throwing water on it as try to end this war by fighting.”

There were also socialists – some of the writing on the wall in Richmond says: “If the workers of all countries united and refused to fight there would be no war."

They came up against an army that was running short of soldiers. In March 1916, conscription for all single men aged 18 to 41 had been introduced. Clergymen, teachers, those indispensable to the war effort and the medically unfit were exempt, but they had to go before a tribunal to prove it.

Those who objected to fighting on moral grounds also went before the tribunal. Advised by a hawkish military man, it sifted the skivvers from the genuine. But even the genuine were expected to join the Non-Combatant Corps (NCC) and report for uniformed duty doing non-frontline jobs in the stores or on transport.

The Darlington Tribunal – an extremely rare photograph of such a body, held in the collection of the Darlington Centre for Local Studies. The photographer appears to be in the dock with everyone looking at him

The tribunals were extremely busy – in early April 1916, Durham had 145 cases before it; Darlington, a Quaker town, had 13, including the Law brothers, Billy, 25, and Bert, 24.

The Quakers created the Friends Ambulance Unit (FAU) to help their members out of their principled hole, and the FAU did valuable work on the frontline in dangerous conditions assisting the wounded without being involved in the wounding.

For the absolutists, even this was too much. They saw the NCC as facilitating the killing, and the FAU as apologising for it. The absolutists refused to wear a uniform or undertake any duties.

At least one of the Law brothers – probably the younger, Bert, a sharebroker’s clerk – was absolutely absolutist, and from his first hearing declared that he was ready to suffer for his conscience.

The Laws don’t seem to have been Quakers. In fact, staff in Darlington library have just uncovered the 1911 census, in which the boys are living at 11, Elton Parade, with their father Thomas, 45, a house painter, and their Staindrop-born mother, Mary, 48. The final column on the census is for the taker to mark down infirmities – whether the resident is deaf, blind, lunatic, imbecile or feeble-minded. Beside Mary’s name, he wrote: “Wife delusional thinks she ought to have a vote.”

Bert and Billy appear to have inherited their radical streak from their mother Mary, who was obviously an early suffragette supporter.

When the Darlington Tribunal refused to grant them exemption, they appealed. They lost, and were ordered to report to the 2nd Northern NCC stationed at Richmond Castle on April 24. They refused.

Lt Spencer, of the military authorities, wrote to them on May 4, but they ignored him, and so they were arrested and brought before Darlington magistrates on May 8.

“They have practically been deserters for the past eight days,” spluttered Lt Spencer. “They are educated men, and I do not think they should be dealt with differently from others, especially when they used their education to set the military authorities at defiance.”

The court, in its leniency, handed them over to Lt Spencer’s authorities, who took them to Richmond Castle – there is a suggestion that some of the objectors were frogmarched through the Richmond streets and arrived at the castle bleeding.

From the Echo archive: Richmond Castle in the 1950s, where the conscientious objectors had been held during the First World War

Once there, they were ordered to put on the NCC uniform and perform NCC duties. They refused. They were striped, forcibly dressed in khaki, and locked in the small cells of the dungeon.

By May 21, there were at least 14 others with them, including Norman Gaudie, a Sunderland reserve team footballer and Quaker, Alfred Martlew, a clerk at Rowntree’s chocolate factory at York, and Arthur Myers, an ironstone miner from Carlin How in east Cleveland.

But other dungeons across the country were also filling up with objectors. From the point of view of the Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener, there were too many men pleading conscience to escape conscription. He needed something draconian to deter them.

On May 29, he selected, apparently at random, four groups of prisoners: 17 held at Harwick, nine at Sleaford, two at Abergele and 16 at Richmond. They were secretly hustled onto a train to Southampton – as it passed through London, one of the 16 threw a letter addressed to York’s Quaker MP Arnold Rowntree out of a window – and shipped to Boulogne.

They were now in a war zone where niceties no longer applied. They had no one to defend them against the military machine. They were told that a previous group of objectors had been executed – a lie.

One of the 16, John Brocklesby of Doncaster, alerted the No Conscription Fellowship to their predicament. To cut down on the need for censorship, soldiers were issued with Field Service Postcard which had phrases pre-printed on them. The men crossed out the phrases that didn’t apply to them and sent the non-contentious communication home. Brocklesby, though, crossed out nearly all the words but left letters which made up the phrase: “I am being sent down to b/long.”

On June 6, the objectors were ordered to Boulogne docks to unload a ship.

Fifteen of the 16 refused. They were confined to punishment barracks and charged with “a wilful defiance of authority”, which carried the death sentence.

On June 13, a court martial found them guilty. On June 24, in front of hundreds of serving soldiers, they were publicly sentenced to be shot by firing squad.

But the most important event in this timeline happened on June 5, off the Orkneys, when HMS Hampshire was torpedoed on its way back from the Battle of Jutland. Of the 662 on board, only 650 died – including Lord Kitchener himself.

There was much public disquiet about the treatment of the objectors. The “conshees” were not popular, but neither was the prospect of their slaughter. Their behaviour was regarded as “unwise, stupid, foolish”, but many thought their treatment was “very un-English”.

The Liberal Prime Minister HH Asquith, who had been uncertain about Kitchener’s strident course of action, had to decide whether to press on with the executions. Rowntree, a Liberal MP who had been opposed to the war from the start, was pressing the PM about the fate of his employee,

Asquith backed down. The sentences were commuted to ten years’ penal servitude although the 15 were not informed. Instead, on June 30, they were moved to a rock-breaking prison in Scotland.

After ten weeks, during which one of their number died, they learnt that their broken rocks were being used to make military roads, and they refused to do any more. The prison, regarded as “Britain’s first concentration camp”, was closed and the 14 were sent to civilian prisons where the humiliations continued – some were forced to wear harlequin uniforms to single them out.

But it didn’t stop some men’s conscience objecting to them being part of the war effort. During the First World War, almost 16,000 men were recorded as objectors, 6,000 being court-martialed and imprisoned with the 1,330 absolutists being locked up in desperate dungeons like Richmond, where they scrawled their thoughts on the wall.

For Martlew, the chocolate clerk, it was too much. He escaped from Wormwood Scrubs, made it home to York where he threw himself into the River Ouse on July 11, 1917, and drowned.

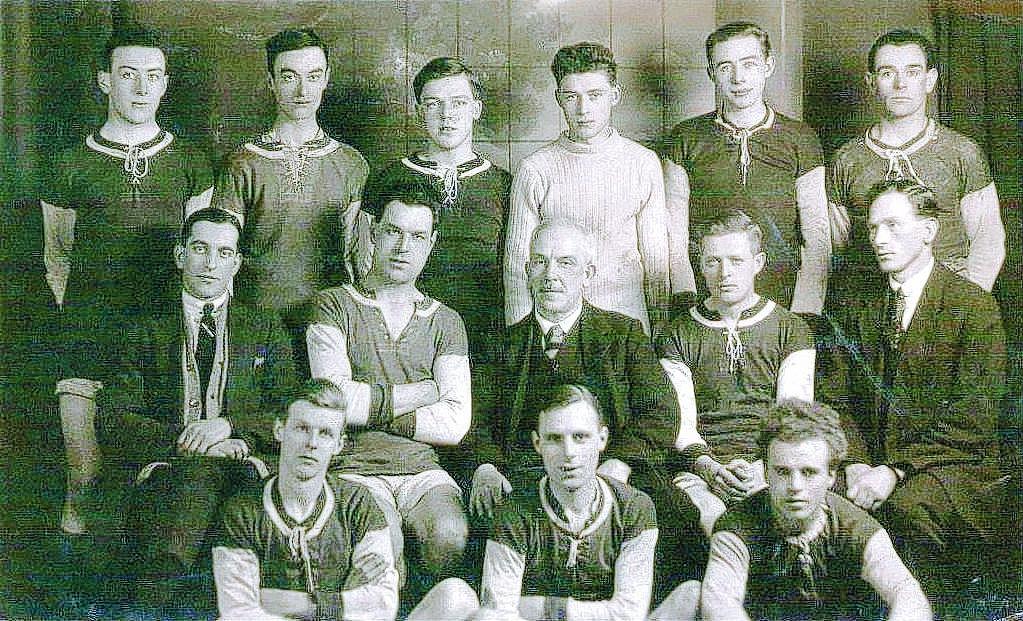

The remainder of the Richmond 16 were released at the end of the war, and the Law brothers returned to the family home in Darlington – the Crown Street library has a picture of them turning out for Blackwell FC in 1919.

Despite their parents being from County Durham, both Bert and Billy had been born in Melbourne, Australia, and soon after the picture was taken, for reasons unknown but perhaps guessable, the family emigrated from Elton Parade for a permanent life Down Under.

- With thanks to Katherine Williamson and Malcolm Wright.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here