IF only walls could talk, what stories would they tell?

The Findmypast website has seen its number of users surge over the course of the pandemic as so many people have spent the lockdown period researching their family trees, and it has recently added a new search function which allows people to find out who is recorded as living in their house when censuses were taken.

Once you have a name, you can then search the site’s other records – old newspapers, maps, electoral rolls, the 1939 Register – to uncover the stories of the people who lived in your house.

More than 70,000 addresses were searched within days of the function being launched as people tried the hidden history of their house.

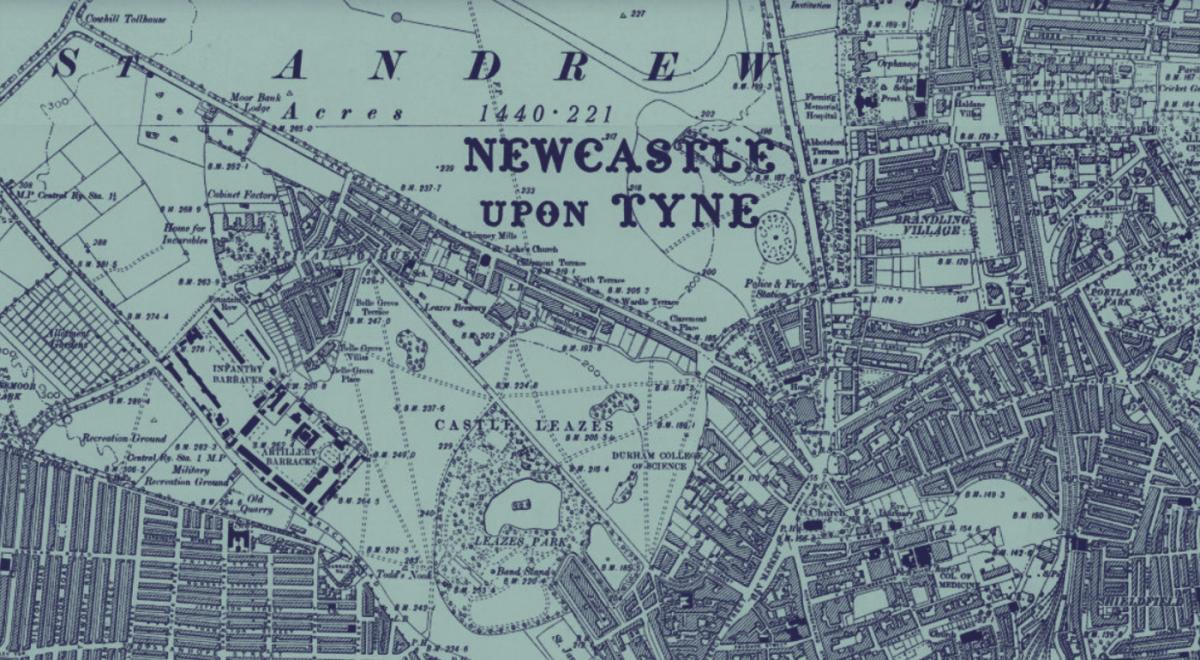

And nearly every house has a story to tell. To prove the point, Findmypast’s researchers have been looking at Newcastle where they have uncovered some amazing stories…

Home of a racer

THE 1911 census found two-year-old George Robson living at 78, Percy Street, in the shadow of St James’ Park, with his 38-year-old widowed mother, Sarah, and six of her other children. She worked as a provision dealer, and his eldest brothers worked as a carter, French polisher and a coachbuilder.

Soon after the census was taken, Sarah emigrated with her children to Canada and in 1924 they arrived in the US.

George became a motor racer, and in May 1946, he won the first Indy500 – a 500 mile race around a track in Indianapolis – after the Second World War. He led the race for the last 138 of the 200 laps, and his car, a bright blue sausage-shaped Adams Big Six is now in the Indianapolis Hall of Fame.

But three months after his triumph, the lad from Percy Street was killed in a race in Atlanta, Georgia: he survived the initial crash, but as he ran from his cockpit, he was struck by at least two other racers. He was 37.

House where Hendrix stayed

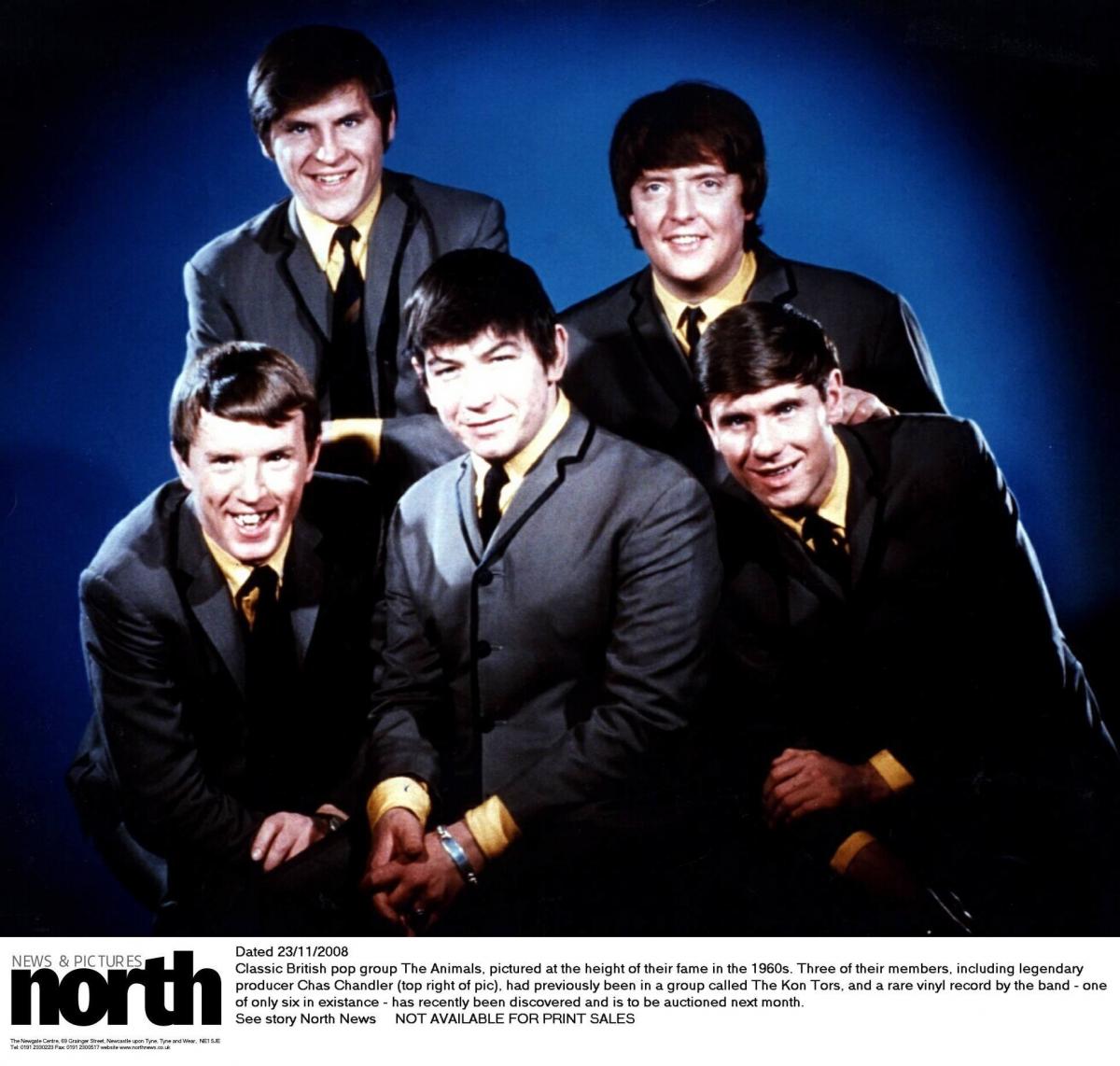

CENSUSES from the start of the 20th Century show that 35 Second Avenue in Heaton was the home of a gas worker, a widow and a winder, but by the 1960s, it was listed as the home of James Chandler, a furniture van driver, who had been born in 1907.

Nowadays, the house has a plaque on it, marking it out as the home of James’ son, Chas, who was The Animals bass guitarist, the manager of Slade, the co-creator of the Newcastle Arena and the man who discovered Jimi Hendrix.

Indeed, Hendrix stayed in Second Avenue on several occasions in 1967 when he was playing gigs in the North-East – including the famous ones at the Kirklevington, near Yarm, on January 15, and the Imperial Hotel in Darlington, on February 2.

Just before those shows, Chas had gone to the red phone box in Second Avenue – his parents hadn’t yet installed one in the house – and called London to see how Hendrix’s first single, Hey Joe, was doing. He was told it had reached No 7 in the hit parade, and a major star was being born…

House with a shocking story

WHEN the 1881 census taker called at The Quarries in Grainger Park Road, they noted that “the head of the family and his wife travelling”. That meant that six-year-old Charles Hesterman Metz and his four-year-old brother, Herbert, and their one-month-old sister, Theresa, were in the care of two servants and a 24-year-old nurse, Judith Murray, from Yorkshire.

Merz’s father was a German Quaker chemist and his mother was from the Richardson family of Tyneside shipbuilders.

Merz became an electrical engineer, best known for pioneering the use of AV voltage and known during his life as “the Grid King”, as he effectively created the National Grid.

He died with his two children in 1940 in London during a German air raid.

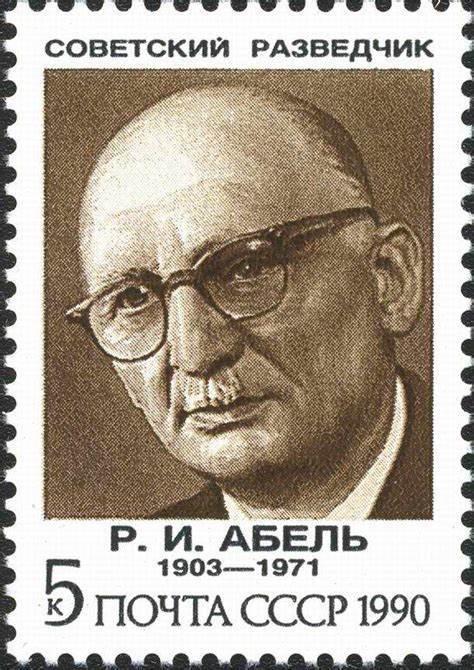

Home of a Russian spy

FINDMYPAST’S records tell how William Fisher grew up in Eleanor Street, North Shields, in a property which had once been home to a Methodist preacher and a police constable.

He lived there with his parents, Heinrich and Lyubov, who had fled Russia in 1901 when their revolutionary activities with Vladimir Lenin had become known to the tsar’s authorities. They initially settled in Benwell, where William was born in 1903 at 140, Clara Street.

Heinrich worked in the shipyards – and probably acted as a gunrunner for the Bolsheviks, sending weapons to Baltic ports – and William attended high schools in Whitley Bay and Monkseaton, where he showed an aptitude for music and languages. He got a job as a draughtsman with Swan Hunter, but before he could go to university, his parents took him back to Russia.

He became a wireless operator for Soviet intelligence, spying on the Germans during the Second World War. The KGB then equipped him with false identities and sent him to New York to command a network of spies.

He lived for eight years amid the artistic community under the name Emil Goldfus until “the hollow nickel case” led to his unmasking.

He had collected the hollowed out coin from a dead letter box and was meant to pass it to another spy but he accidentally spent it. The coin spent seven months in circulation in New York until a newsboy dropped it, causing it to break open to reveal a microphotograph which had tiny numbers on it – a code.

When William/Emil was arrested, he gave the name Rudolf Ivanovich Abel. The Americans never worked out his true Geordie identity, but they sentenced him to 30 years in prison – narrowly avoiding the electric chair. After serving four years, he was exchanged for Gary Powers, the US pilot who had been shot down by the Russians while flying a spy plane.

In Russia, he was hailed as the spy who never broke down, and it was only when “Abel” died in 1971, that the Russians buried him in a grave which revealed his Newcastle name. In 2015, Steven Spielberg featured his story in the film, The Bridge of Spies.

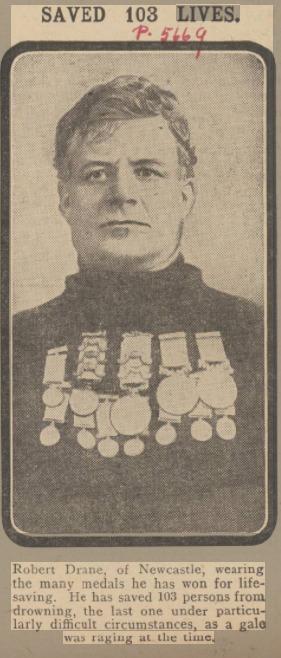

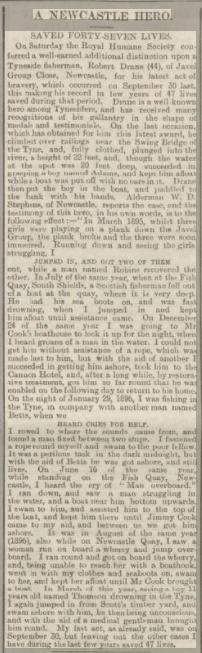

A hero’s home

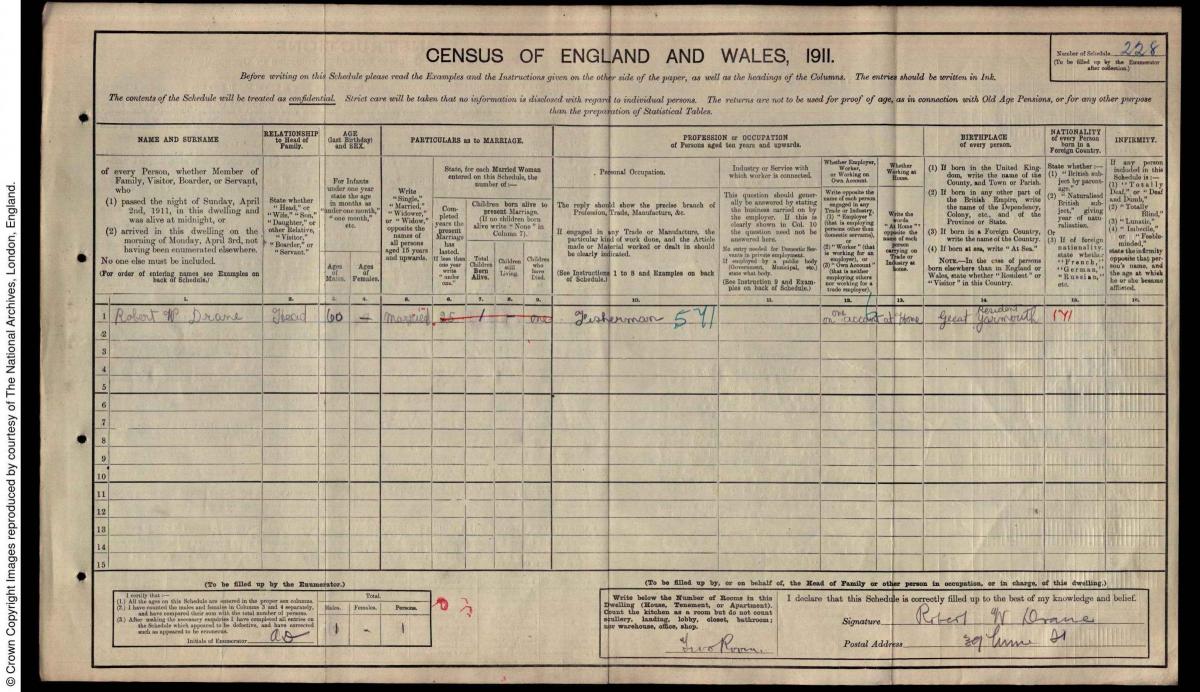

THE 1911 census found 60-year-old Robert Drane, which it recorded as a fisherman, living on his own in 39, Lime Street, in Byker, which is near where the Ouseburn joins the Tyne. He was, says the census, born at Great Yarmouth.

It doesn’t say that he was a hero – although newspaper reports on the website tell how over 62 years he saved 115 lives, largely by diving in and dragging drowning people out of the Tyne.

There was the Scottish fisherman he fished out at South Shields, the two girls he pulled out when the plank they were playing on at Javel Groupe snapped, the policemen he saved when their boat capsized, the boy Adams he rescued by diving in fully clothed 22ft near the Swing Bridge to keep him afloat until a boat could reach him…

Robert’s last rescue was when he was 76, a few months before his death, when a four-year-old neighbour fell in at North Quay and he pulled the lad out.

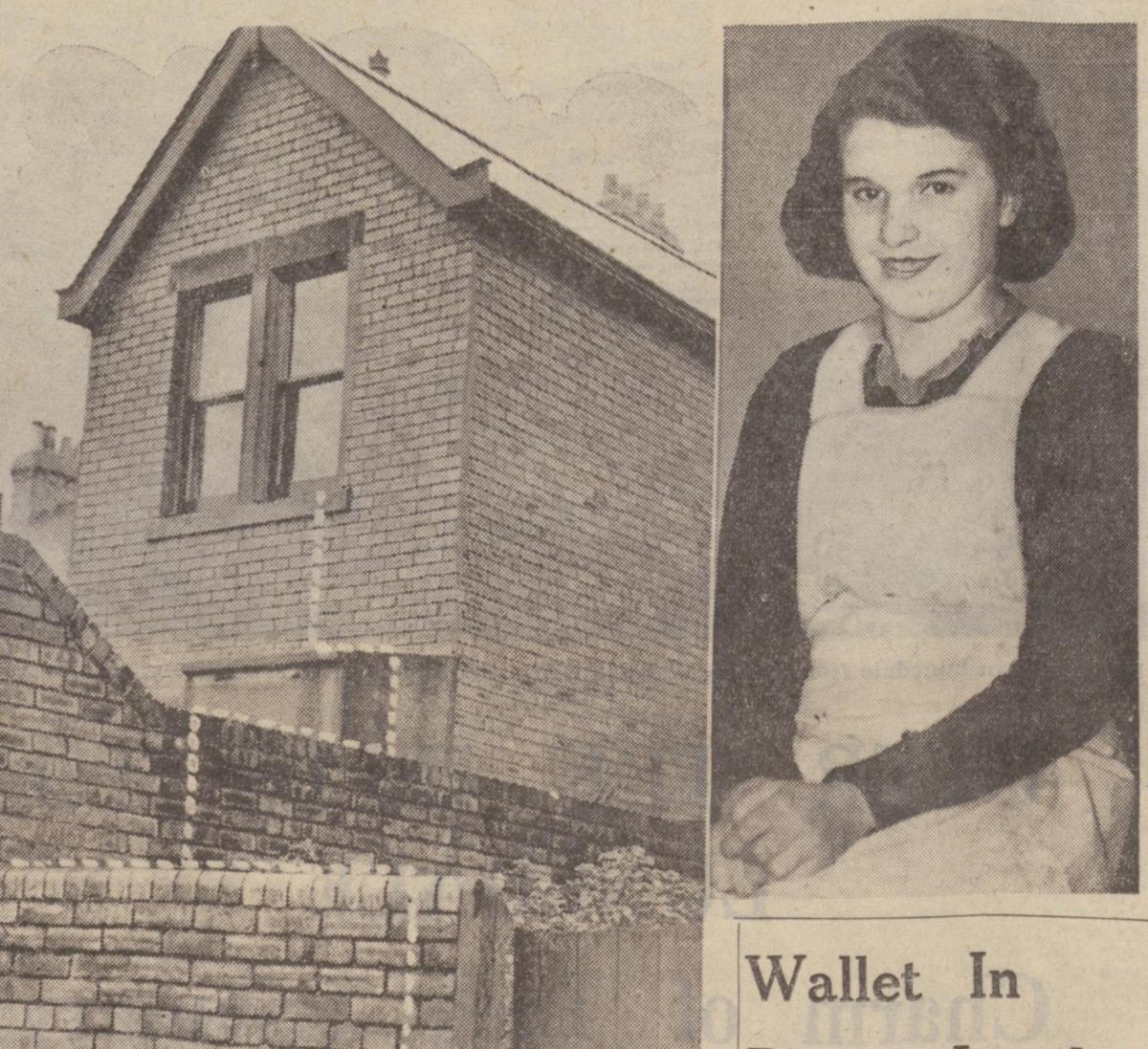

House of a fire drama

THE 1931 census was destroyed by fire during the Second World War, and the 1941 census didn’t take place, so the 1939 Register is vital to researchers. It was taken on September 29, 1939, and it was used to produce identity cards and then rationing cards.

The register’s page for Dinnington Colliery, which is near Wideopen to the north of Newcastle, has been repaired with sticky tape but you can still make out that in a large house called Claremont, 15-year-old Ella Gray worked as a servant for Dr Angus McLeod, looking after his children: Margaret, five, and Donald, two.

A fortnight after the register was taken, Ella was sleeping in the same room as the children when fire broke out. “I smelt burning and heard wood crackling,” she told the Newcastle Weekly Chronicle. “I jumped out of bed and tried to open the door, but it would not open. I forced the window up, lifted the little girl out and swung her to the roof of an outhouse and then handed Donald down to her.”

Ella helped the two children off the roof, onto a wall and down to safety before herself tumbling off and scraping herself very badly.

Supt Hann of Gosforth Fire Brigade said: “That little maid did a very fine piece of work in so coolly tackling a very dangerous situation. It was a remarkable and courageous thing for a girl of her years.”

He said that the heat had caused the paint on the door to blister so it would not open. If it had, he said, she would have received “the full force of the smoke and flames rushing up the staircase” and probably none of them would have survived.

Go to Findmypast for more details. You should receive a free trial after which subscriptions start from £6.67 a month, depending on how long you sign up for

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here