IN 1914 in Bishop Auckland, there were 37 hotels and pubs. There were 21 confectioners, 17 butchers, 14 greengrocers, 14 boot and shoe makers, nine hairdressers and seven banks.

We know all this because Peter Daniels has spent lockdown analysing a street directory of the town.

And, surprisingly, there were five artificial teethmakers: Andrew Jameson of Cockton Hill Terrace, Aubrey Harding of Albert Hill, Alexander Mudie of Raby Avenue, Smith & Gavin Ltd of Newgate Street, and Richard Henry Critchley of South Road.

This means there were the same number of artificial teeth makers in Bishop Auckland as there were fried fish shop proprietors, and there were more artificial teethmakers than there were fishmongers, dressmakers or bakers (four each), or building societies, pianomakers and cinemas (three each).

In fact, there were only three dentists in the town – but five artificial teethmakers.

But out of what would they have been making their teeth?

The popularity of artificial teeth grew as sugar consumption grew in the 17th Century. The earliest were made out of ivory, from elephants, walruses or hippopotamuses.

Ivory, though, didn’t look real and decayed to a tea-stained brown, so real teeth were used: animal teeth or human teeth, either taken from dead bodies – at the Battle of Waterloo of 1815, about 50,000 young men died and the continent was awash with “Waterloo teeth” for decades afterwards – or sold by poor people or, sadly, forcibly surrendered by the lower classes, like slaves.

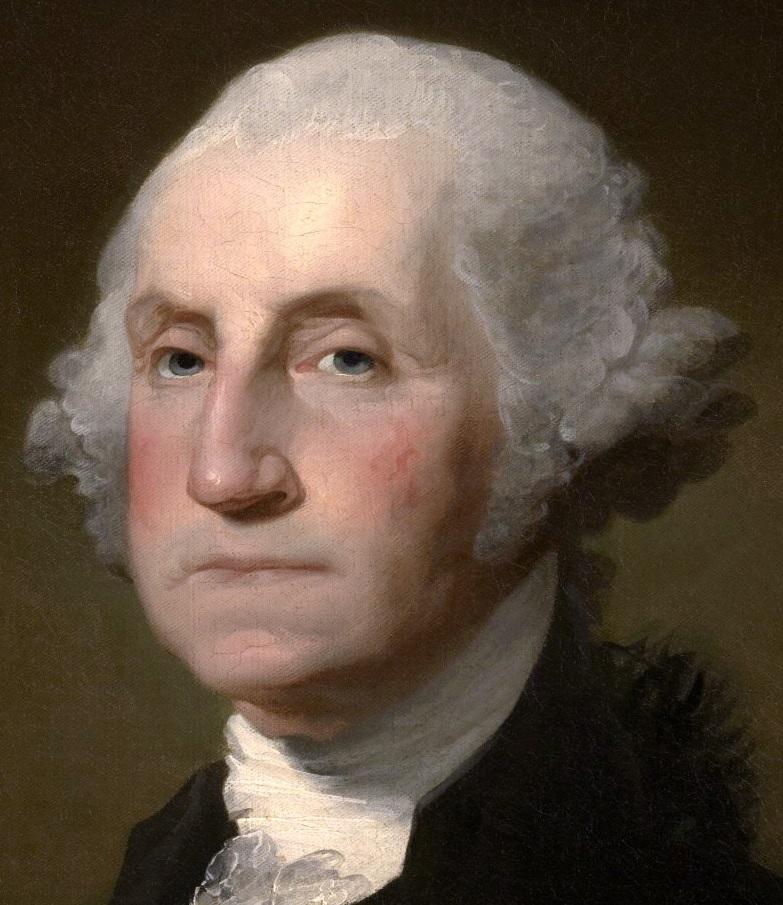

George Washington was one of the first celebrated false teeth wearers. He lost so many teeth in his twenties that he was reduced to eating pickled tripe, which slipped down easily, and at the age of 49, he had his first set of falsies fitted. It was made out of hippo ivory and included human, horse and donkey teeth.

He was 57 when he was first inaugurated as US president, and he had just one tooth left. His denture-maker

Before the Revolutionary War, Dr. John Baker made a partial denture of ivory to wire to Washington’s remaining teeth. Later, Dr. John Greenwood of New York fashioned an advanced denture out of hippopotamus ivory for the president’s inauguration in 1789. Dr. Greenwood even made a hole in the dentures for Washington’s final remaining tooth, which Washington later gave to him as a thank you.

Two big scientific advances helped the artificial teethmakers: firstly, vulcanite, in the 1850s, was a flexible rubber that allowed the dentures to sit comfortably on the jaw rather than be wired in, and then, in the late 19th Century came a new king of porcelain. Previous porcelain dentures had been very white but were like having a mouth full of crockery which cracked and chipped, but as the century wore on, it became more durable.

And so, probably, all those artificial teethmakers in Bishop Auckland were fashioning their replacements out of porcelain, and that’s the whole tooth…

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here