IN Sadberge 100 years ago, there was a storm in a teacup – or at least a wave on the surface of the stagnant village pond.

Hamper’s Pond stood on the east side of the church, and in wet weather it was 150ft by 60ft as it filled with rainwater running off the road.

In dry weather, the pond shrank and became squiffily stagnant, giving off “unpleasant odours”. The cattle drinking from it didn’t seem to mind, but the Medical Officer and the Parish Council were “unanimous in the opinion that the pond is a nuisance and a danger to health”.

It therefore had to be filled in.

But the former rector of Sadberge, the Reverend W Lancaster Taylor, said: “I deeply regret such a proposal and I deplore such vandalism.”

Because, he said, the pond was the last water-holding remains of a moat that once encircled a Roman stronghold built on the highest hill in the district with views east to the coast and west into Teesdale.

“Sadberge has not been blest with residents who value its ancient relics,” said the retired rector. “I do hope nothing will be done to destroy this one.”

Sadberge is at an important crossroads where the main east to west road from Stockton to Darlington crossed a Roman road, which ran from York in the south to Chester-le-Street and then the wall in the north.

This road – called Cade’s Road by some and Rykeneild Street by others – crossed the Tees at Middleton One Row, over “Pons Tisa”, which may just have been a ford.

From the river, the Romans marched three miles up the hill to Sadberge where they made a camp. In the fields to the east of their road, behind the Tuns pub, you can still see the markings and terraces of their camp.

A Roman road usually ran through the centre of a settlement, and so antiquarians like Mr Taylor also looked to the west for evidence of their activity. They found it in Beacon Hill, which is now a line of houses beside the A66 but which could once have been a Roman signalling station.

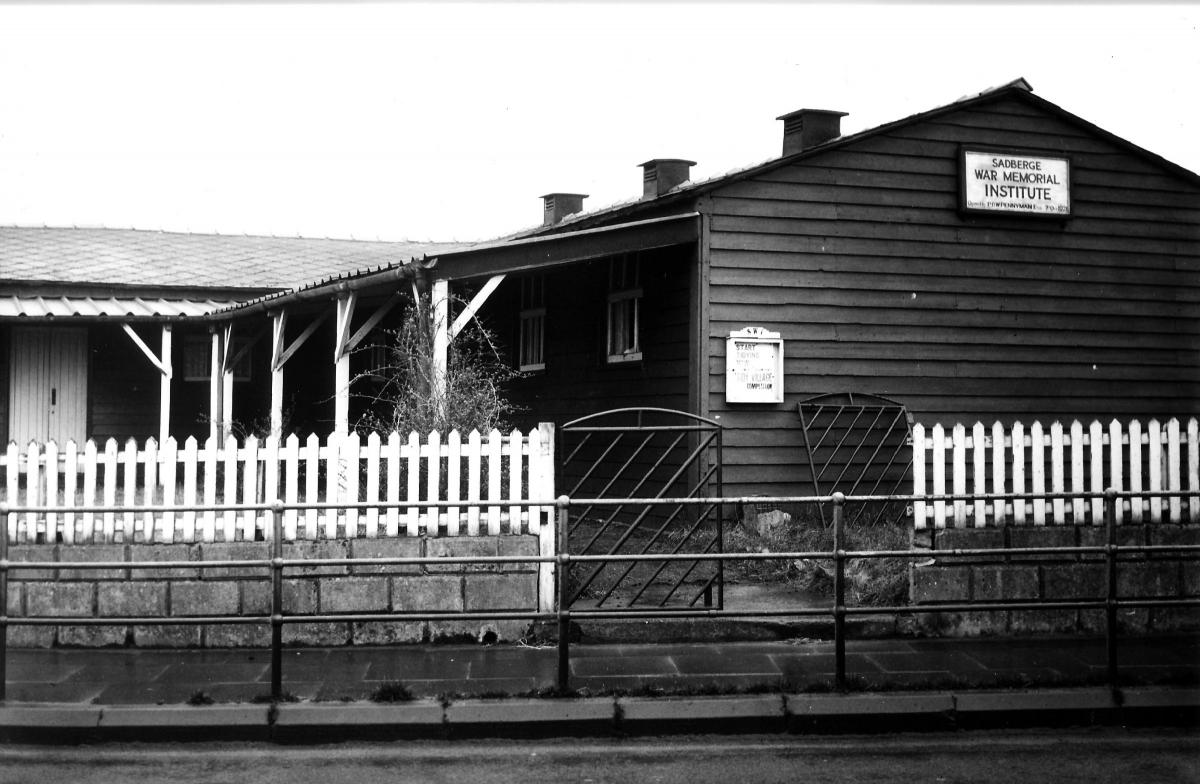

And they found it in the church, which sits on the very top of the hill surrounded by what, even to this day, looks as if it could once have been a moat.

Mr Taylor believed this was the site of the Romans’ fort, their stronghold into which they retreated whenever they came under attack.

And, said Mr Taylor, who was rector from 1887 to 1911 and wrote a book about the village which is bigger than the village itself, they did come under attack, possibly from the Brigantes, the native people who lived inside earthern fortifications at Stanwick St John.

Mr Taylor said there was a local legend of a battle fought on the south side of the moat, and when he dug a grave on the southern edge of the churchyard “to my surprise and grief, skulls were as numerous as potatoes in a potato field”.

To some people, finding dead bodies in a graveyard is not a news story, but Mr Taylor felt there were so many that this could have been the scene of the mythical battle.

The Romans left Britain around in AD420, and in the Saxon period that followed, Sadberge became the capital of the Tees Valley, probably because of its lofty position. It ruled a strip of land – known as a wapentake – from Barnard Castle and Middleton-in-Teesdale in the west to Hartlepool in the east.

Mr Taylor believed that a simple Saxon church was built on the site of the Roman fort, but because the people wouldn’t plodge across the moat to prayer, the ditch on the south side was filled in.

Over the centuries, the soil on the other three sides tumbled in. In 1806, George Soakel flattened the north side to build a garden; in 1817, Thomas Gamble did the same on the west.

And so only the east side remained. Old maps show a definite water feature strangely shaped like Y-front pants, but not even Mr Taylor’s protest could stop the plug being pulled on the old moat. Exactly 100 years ago, it was filled in.

Today, the church remains on a raised island with splendid views over the surrounding countryside, and the old moat can still be traced in its shadow, although it is no longer deep enough to hold any water.

THE east side was the scene of what 100-year-old newspapers refer to as “Hamper’s Pond”. Today it is called Hampass and is a delightfully secluded and green depression where there is a children’s garden.

SADBERGE’S Saxon church fell down and was replaced by a Norman one in the 11th or 12th Century. In 1831, the Norman one was demolished and replaced by the existing church.

The builder used some of the ancient stone to shore up the wall which keeps the church in its lofty position. The rest he carted into Darlington where he was building a wall to keep the River Skerne in check between Priestgate and Tubwell Row. A few leftover stones he built into the Glittering Star pub.

When Mr Taylor discovered this story, he lamented the “vandalism” and went looking for Sadberge’s lost stones. In the kitchen of the Glittering Star he found two that took his fancy: one medieval from the 13th Century had a badly weathered carving showing Our Lord Triumphing over Satan, and a 9th Century Saxon stone on which those with a good imagination can see Adam and Eve sitting in the Garden of Eden.

Mr Taylor chipped the stones out of the pub and returned them to Sadberge, and in 1904 they were built into the church porch.

THE other watery story connected to Sadberge concerns the boulder on the village green.

Because of the village’s raised position, in 1886 the Stockton & Middlesbrough Water Board built a reservoir there to hold 12m gallons of Tees water. The board was supposed to be building six reservoirs up in Teesdale to collect the water which would flow down the river to the Broken Scar pumping station, from where it would be pumped to high-up Sadberge to be stored until the people and industries of Teesside required it.

When the diggers at Sadberge reached about 12ft down, they struck an unusually large boulder. Historian, naturalist, businessman and prominent Conservative William Wooler, of Sadberge Hall, came rushing over and had the three-and-a-half ton stone hauled out of the hole.

He helped identify it as an erratic: a boulder that had travelled on a glacier 80,000 years ago from the top of Cumbria down the Tees Valley and was left when the ice melted at Sadberge.

Now, because of Sadberge’s Saxon history as a wapentake, or regional capital, when it fell under the control of the Bishop of Durham in 1189, he was given the additional title of Earl of Sadberge. In 1836, the bishop’s non-religious powers were abolished and, along with his titles, were returned to the Crown.

A few months after the discovery of the boulder, Queen Victoria celebrated her Golden Jubilee. Mr Wooler installed the stone on the green in commemoration of her 50 years, and he hailed her as “Queen of the United Kingdom, Empress of India and Countess of Sadberge”.

This last title seems to have been Mr Wooler’s invention. He’s right that the Queen was the holder of the title, and he’s also right that the female equivalent of earl is countess.

But equally, there is no evidence that Her Majesty ever used the title until it was nailed onto the side of a stone, and it is not clear that her successor, Queen Elizabeth II, has ever called herself “the Countess of Sadberge”.

It would, though, be nice to think that she did.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here