Eden by name, but not by nature. It was so bad, in fact, that one suggestion was to drop a bomb on it, but people down South had other ideas, as Echo Memories reports.

EDEN should be “a place or state of great delight or contentment”, but in Durham 70 years ago, it was anything but.

It was simply a state. Such a hellish state, in fact, that the best way to improve it was to drop a bomb on it.

Instead, though, the people of Bedford more than 200 miles away took pity on it.

For Echo Memories – and the accompanying blog on The Northern Echo’s website – this is a return to Eden Pit, as we were inquiring about it a couple of weeks ago.

Readers have since shown us the right direction.

It lay to the south of Middridge, itself a village between Shildon and Newton Aycliffe.

Middridge Colliery was sunk by the Weardale Iron and Coal Company with two pits: the Eden (1872) and the Charles (1874). A threequarter mile tramway ran along the western edge of Middridge, connecting Charles with Eden. At Eden, the coal dropped down onto the original Stockton and Darlington Railway.

The colliery quickly blossomed – in the 1890s, 420 men and boys were employed producing 600 tons of coal a day – and then rapidly faded.

It was closed by the end of the First World War.

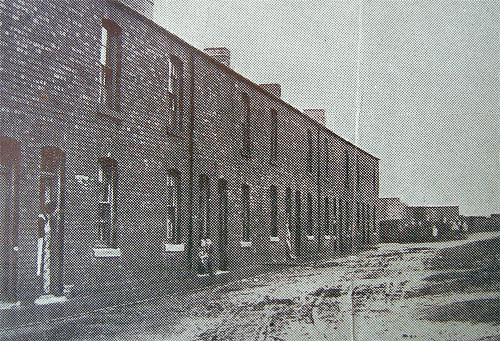

This left the 37 houses of Eden Pit full of miners with nothing to mine.

The community fell into such a state that former North-Easterners who had emigrated to Bedfordshire formed the Northumberland and Durham Association to assist it. They despatched HW Liddle, headmaster of Bedford Modern School, to see what could be done.

“In prosperous times,”

wrote Mr Liddle in the Bedfordshire Times of March 8, 1935, “the neighbourhood resembled an active theatre of war with the horizon brilliantly lit up by the glare from coke ovens at night and the countryside filled with the busy life of teeming throngs of colliers by day. Now operations have almost completely stopped, and today the area is derelict.

“In the midst of this dead region is the stagnant, suffering village of Eden Pit.

Here are three parallel rows of four-roomed houses, with the usual lines of coal houses and earth closets between. The windows and doors are in many cases illfitting, the streets are worse than the ordinary unadopted road.

“A biting wind sweeps through the place, whipping a touch of colour into the pallid cheeks of the inhabitants and turning the children blue with cold.

“Attached to the houses are small gardens and a few plots of land, all sick with repeated cropping of potatoes and the lack of the all-important manure.

“Inside the houses a different picture presents itself in piquant contrast.

Everything is spotless. The Durham housewife is houseproud, and keeps her sticks of furniture, her hearth, her cooking utensils bright by constant scrubbing. She manages, somehow or other, to make a cosy home of these small rooms into which one steps straight from the street. She makes cloth mats for her floors and sees to it that the children at any rate are warm in bed.

“Her man, too, keeps his chin up and has not yet lost his self-respect or his sense of humour.

“There is something heroic in the patient endurance of these folk, and one feels that if only the longed-for work came to them, they would at once set about regaining the tone which they have slowly but surely lost.

“How could it be otherwise in a population of 163 souls with four men only at work?

The mere packing of 43 men, 46 women and 74 children into 37 small houses is bad enough: with practically the whole of the men idle it is deplorable.

“The only amenity to be found is a small workshop set up in two disused cottages by the wife of the local MP: it gives a few of the younger men occupation in the making of simple articles of furniture.”

The MP was Hugh Dalton.

His wife, Ruth, won the Bishop Auckland seat in a by-election in 1929 and kept it warm until he was available to win it in his own right in the General Election three months later – this makes her the shortestserving female MP in Commons history (we’ll post her story on the Memories blog this morning).

Mr Dalton represented Bishop until 1959 and famously resigned as Chancellor of the Exchequer when he accidentally leaked his 1947 Budget.

Notwithstanding the Daltons’ work, Mr Liddle was pessimistic that the pits would re-open or that a new industry would start up at Eden Pit. “The best course to pursue would be to remove the inhabitants and drop a high-powered bomb on the site,” he wrote. “A clean sweep, however, is impossible. Means must therefore be sought to make life more tolerable in Eden Pit.”

The unemployed miners were at least trying. “A social service centre has been formed, the committee elected, seeds and tools and manure for the small plots requisitioned and a bank manager in Shildon has taken on the treasurership,”

he wrote. Plus, men from Bedford were sending unwanted clothing and collecting money.

“Much remains to be done,” concluded Mr Liddle.

“Allotments to be secured, a hut to be erected, streets to be levelled, a garden to be made, a playing place for the children to be provided, the houses to be painted outside and redecorated inside.

“There must be many in this generous town of Bedford who would wish to be associated in this work of regeneration. Eden Pit can never become a Garden of Eden, but it need not remain a Slough of Despond.”

How far this all went, we don’t know. Christmas presents and hampers were certainly distributed in the terraces – while the women were grateful, some men had misgivings about accepting charity – and older people in Middridge remember that a few Edenites went to Bedford for training.

But for all the good intentions, there was no hope in Eden. The three terraces were demolished in the early Fifties.

■ Many thanks to Anne Clarke of Middridge for her help with today’s article AND what of Riseburn, Eden Pit’s neighbour on the south of the railway line? Its terraces formed three sides of a square facing the railway line. In the middle was a Primitive Methodist Chapel.

There were 41 houses in Riseburn, and they look more substantial than the slim terraces of Eden Pit.

Riseburn was reached by Walker’s Lane, a lane still popular with walkers, although it seems to refer to a John Walker who owned a field thereabouts when Middridge was enclosed in 1638.

Riseburn was built between 1860 and 1890 and was demolished in the late Forties. No one remembers why people needed to live in this isolated spot, but it must have been an industrial community.

Don Ferguson is one of those who has been in touch.

His wife Betty’s family moved to Riseburn from Arkengarthdale and then emigrated to New Zealand after the 1926 strike.

We’d love to hear any other snippets about these lost communities.

DON also points out that both communities stood near the Shildon marshalling yard where, from 1840 onwards, thousands of wagons stood in sidings waiting for their cargoes of Durham coal. “It was the world’s first marshalling yard and for years it was the world’s biggest,” he says. “It was a showpiece of which the Stockton and Darlington Railway was very proud – and why not?”

MIDDRIDGE has a newly-formed local history society. Its third meeting will take place at 7pm on Thursday, October 8, in the village hall, when there will be a talk on the Roman remains at Binchester. All are welcome.

Entry is £2 to nonmembers.

Call 01325-316257.

SEVERAL people have mentioned that the pits on last week’s map of South Church weren’t quite in the right places.

Sorry.

Adelaide Colliery, says Harry Kipling, should have been closer to Shildon.

“My father’s first job was down Adelaide Colliery and he told me there were frequent cave-ins and the lights went out,” he says.

“He just caught hold of the tail of a pony and in the dark it took him through the passage from one shaft to the other and got him out.”

Brick to the future

THE signs have just gone up on a re-named pub in Blackwellgate, Darlington, and a “for sale”

sign has just gone up outside a curious house on the road up from Blackwell Bridge.

The pub is now The Hoskins; the house was designed by the architect after whom the pub is named; GG Hoskins.

GG Hoskins is the Tees Valley’s most influential architect. Most late- Victorian Gothic two-tone buildings, from banks to town halls, are his.

It is said that when he won the contract to build Blackwell Hill – a mansion built as an orphanage for a member of the Backhouse banking family (we’ll get her story up on the blog, as well) – he trialled his brick colour combinations on a lodge first. The Backhouses must have liked the orange and cream effect because when the lodge was complete in 1869, Hoskins started on the mansion.

That mansion was demolished decades ago, but the lodge – engulfed by trees and now called Blackwell Hill Cottage – will be auctioned by estate agents Smiths Gore on October 26 in the Blackwell Grange Hotel.

It was last sold by auction in 1976 for £11,500. In 2009, when it is in need of complete renovation, the guide price is £225,000 to £250,000.

Perhaps the purchaser can somehow disguise the unsympathetic extension so it doesn’t destroy Hoskins’ two-tone design.

The Hoskins pub was, from 1998, known as Humphrys. For 130 years before that, it was The County. And for 70 years before that, it was the Black Bull. As such, it achieved literary fame.

In chapter four of Sir Walter Scott’s 1818 novel Rob Roy, the central character, Rob, a Scottish border raider, stays one night in the Black Bear hotel in Darlington.

For Black Bear read Black Bull – an obvious place for a traveller to stay a night, as Grange Road and Blackwellgate were then part of the Great North Road that swept from London to Edinburgh.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel