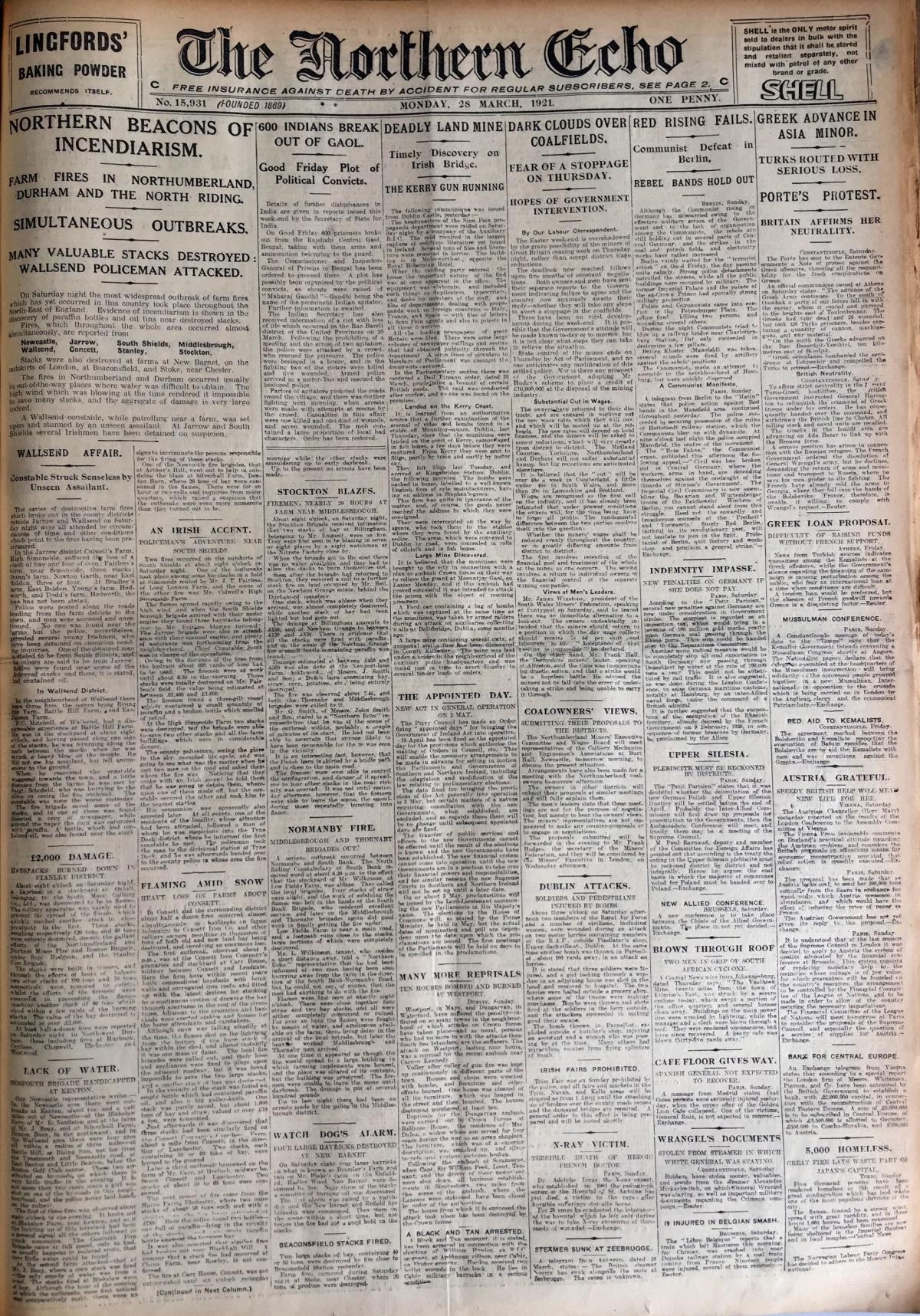

“ON Saturday night, the most widespread outbreak of farm fires which has yet occurred in this country took place throughout the North-East,” reported The Northern Echo exactly 100 years ago this week. “Evidence of incendiarism is shown in the discovery of paraffin bottles and oil tins near destroyed stacks.”

That front page from history is reproduced in our centre spread today because it marks the shocking moment that Irish terrorism came to our region.

Several dozen haystacks were ignited around 8pm on March 26, 1921, from Tyneside down to Teesside.

“They all occurred simultaneously and are suspected to be the work of Sinn Fein,” said the Darlington & Stockton Times a few days later.

A century ago, Great Britain had tumbled out of the First World War and into a guerrilla war with the Irish who wanted independence. Most of the violence, with more than 1,000 killed, was on the island of Ireland but there was also a battle to win influence and change on the mainland.

In 1920, the Irish Self-Determination League was formed with 25 branches in Durham and Northumberland made up of people of Irish descent. Its inaugural event was a march through Durham on August 8, 1920, which was attended by thousands.

The ISDL was supposed to be above politics, but it covertly recruited both men and guns for the IRA.

It is likely that the outbreak of violence came because of contacts made in the league.

The first indication that the troubles of Ireland were spreading to the North-East came on March 7, 1921, when the Echo reported how “outrages attributed to Sinn Fein” had been discovered on Tyneside.

It said: “For some weeks there have been persistent rumours that the operations of those engaged in the warfare of incendiarism would be extended to Newcastle…special guards have been posted at all the shipyards, the big industrial works, on the important railway bridges, and on the High Level Bridge which connects Newcastle with Gateshead, or, as an ironical Novocastrian once put it, “connects Gateshead with civilisation”.”

This alertness had prevented Tyne Dock from being torched, although oil had been spread.

Three weeks later came the night of haystack fires.

In Consett, half a dozen were fired on farms belong to the iron company. “Although snow was falling steadily at the time, the flames shot up like lightning from the bottom of the huge stack of hay,” said the Echo.

On Teesside, haystacks in Billingham, Newham, Acklam, South Bank, Normanby, Eston, Linthorpe and Grove Hill were ignited in an outbreak of “premediated incendiarism”.

“The fires occurred usually in out of the way places where water was difficult to obtain,” said the Echo. “The high wind rendered it impossible to save many stacks and the aggregate of damage is very large indeed.”

“While the Stockton brigade were busy in their area,” said the D&S Times, “both the Middlesbrough and Thornaby brigades were engaged on the Yorkshire side of the river.”

Hundreds of pounds of damage was caused, but no one was hurt.

On Tyneside, seven men in their 20s were arrested. Five of them were called Patrick and all had Irish surnames. No one on Teesside was apprehended.

There was a second night of more severe violence, on May 21, 1921, when industry on Teesside was firebombed, including a waterworks at Stockton which caused localised flooding. This episode saw the only casualty of the campaign: a pony was burned to death in its stable.

This seems to have been the last of the organised attacks as on July 9, 1921, a truce was agreed between the British government and the IRA. This led to the partition of Ireland and the creation of the Irish Free State at the end of the year. The Irishmen in the North-East stood down – but it was not the end of the Troubles.

L With thanks to David Walsh, of east Cleveland.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel