ICEHOUSE-MANIA broke out in the 1760s and lasted until the 1820s. Anyone who was anyone was building an icehouse: a giant, egg-shaped, brick-lined subterranean chamber into which ice was carted from a pond or river in the winter so that in summer, it could be used to cool his lordship’s drinks or chill his desserts.

The first icehouse in this country was built for King James I in Greenwich Park in 1619, and the concept of keeping ice from the depths of winter until the height of summer was so mindboggling that in 1661, Edward Waller wrote a poem to the royal icehouse:

Yonder the harvest of cold months laid up,

Gives a fresh coolness to the royal cup,

There ice, like crystal, firm and never lost,

Tempers hot July with December’s frost.

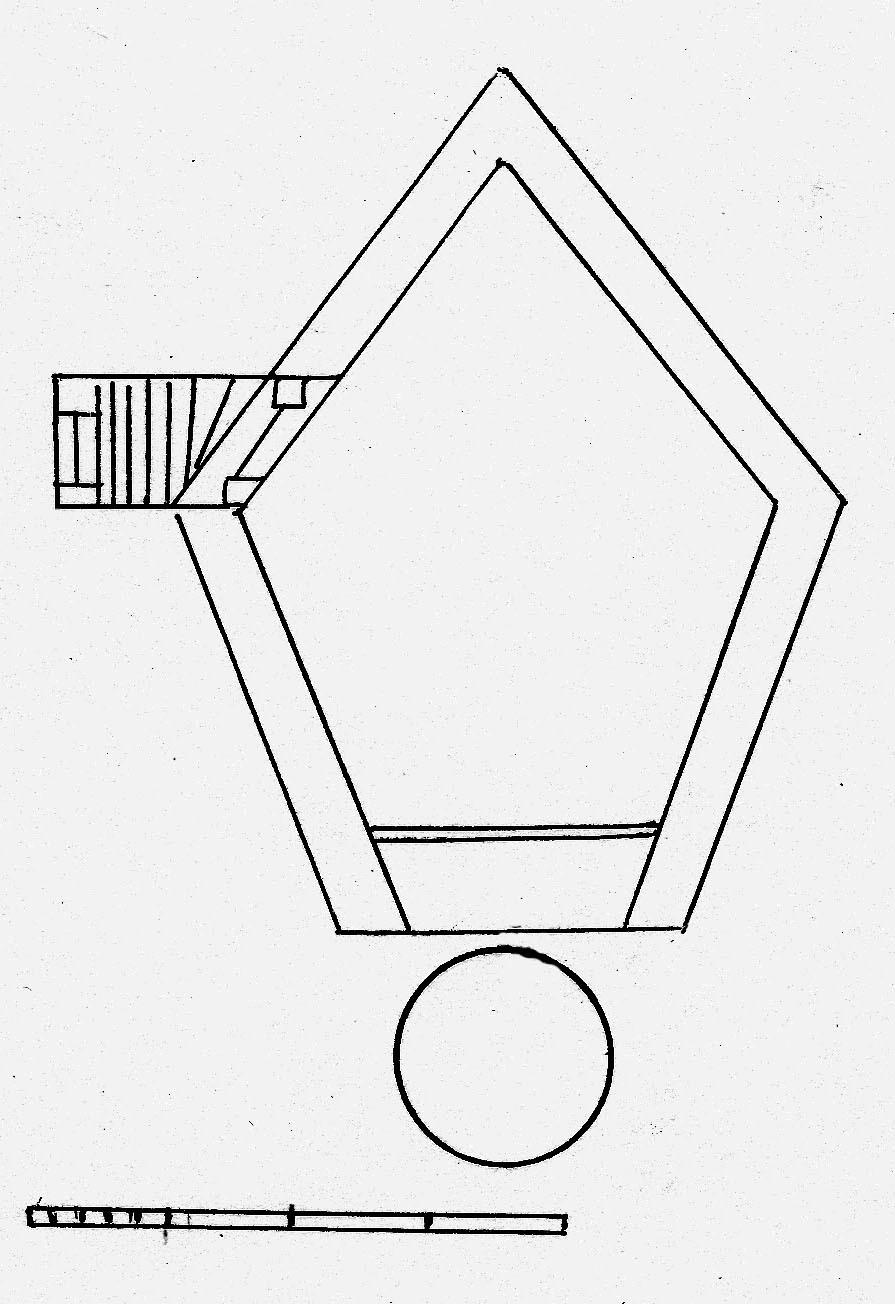

Nearly all icehouses were built with about four-fifths of the chamber below the ground, and about one-fifth above ground, with insulating soil heaped over the top of it. A ground level passageway, with sealed doors, provided access to the chamber, and at the bottom of it was a drain so that meltwater could escape without filling up the whole house.

The ice was sourced either from a natural beck or lake, or from a manmade pond, dug deliberately close, like at Raby Castle, to the icehouse.

The ice was packed into the chamber with layers of straw, sawdust and old carpet which acted as further insulation. In such conditions, ice lasted for six months; a good icehouse would take 18 months to thaw out completely.

The ice stored in a rodent-riddled icehouse was not itself consumed, but its coldness was. It was packed into kitchen ice chests in which a dessert was made, and Antiques Roadshow sometimes shows elaborate Georgian wine coolers in which bottles were surrounded by ice to chill.

As transport improved over the course of the 19th Century, it looks as if those who needed ice were able to import it fresh from Scandinavia. From the 1840s, stately home kitchens were fitted with ice chests, made of wood but lined with tin or zinc, into which a daily delivery of ice slabs was fitted.

Therefore, the mania faded for keeping your ice for months on end mixed up with straw and rats in a manky hole in the ground.

When Carl von Linde patented his liquefying gas refrigerator in 1876, the only use for an icehouse was as out-of-sight storage.

So in the North-East, the golden age of icehouse building was between 1760 and 1820. In recent weeks, with readers’ help, we’ve been trying to compile an itinerary of icehouses. A fortnight ago, we finished our North Yorkshire survey; now let’s see what our loyal correspondents have unearthed in County Durham…

MARGARET ANDERSON has a castle’s icehouse in her back garden. She lives in Walworth, just outside Darlington, over the road from the castle which is now a hotel.

Her house was built beside what old maps describe as an “ancient quarry hole”. Perhaps it was from this very quarry that the original stone for the castle was dug in 1150 (the last stone to be taken from the quarry is believed to have gone to build the Teesside Airport runway at the start of the Second World War).

With their steep, shielding sides, quarries are good places in which to build an icehouse, and Walworth’s dates from the typical 70 year icehouse era from 1760 to the 1820s.

Can we be more precise? Well, it may be worth pointing out that in 1759, at the start of that era, Newcastle wine merchant Matthew Stephenson bought Walworth Castle for £16,000. He only stayed until 1775 but he, more than most, would have call for an icehouse.

“It is in good condition,” says Margaret, “although only about a metre of the entrance tunnel still exists. The chamber drops down from the entrance about 6 to 8ft and the top is a brick-lined dome, all intact.”

BRANCEPETH CASTLE, to the north of Spennymoor, has an icehouse which today is on Brancepeth Castle golf course.

“The icehouse is in a wooded area, steep sided, with a stream in the bottom, the first fairway running parallel above it,” says Phil Dyer, a former golf club committee member. “A couple of hundred yards downstream, where the second hole crosses the beck, there's a larger flatter area - there could well have been a pool there once and so a source of ice.”

It appears to come from the classic icehouse era, because Brancepeth Castle was bought in 1796 for £76,000 – which makes Matthew Stephenson’s purchase of Walworth Castle for £16,000 look a bargain – by William Russell.

His family had had estates in Cumbria and William had set up a bank in Sunderland. He had the great good fortune that one of his clients, the owner of Wallsend Colliery, went bust, meaning the bank took possession of the colliery. Shortly afterwards, a 6ft thick seam of the finest quality and easily minable coal was discovered in the colliery. “Wallsend coal” became a by-word for the finest coal to be exported from the Tyne, and William Russell’s fortune was enormous.

In 1791, he bought Hardwick Hall at Sedgefield (which had an icehouse) and five years later, Brancepeth Castle. Brancepeth may well have been a speculative purchase with a view to exploiting the coal beneath it, but his son, Matthew, seems to have loved the place, and lavished anything up to £300,000 on it.

Matthew died in 1822, and his son William inherited. Although the second William was a County Durham MP, Lord Durham described him as “a confirmed lunatic” and he rarely visited Brancepeth, spending most of his time sailing around the Mediterranean on his yacht.

The Brancepeth icehouse would therefore pre-date William’s inheritance, probably built between 1817 and 1822 when Matthew was doing the bulk of his work.

In his deerpark, Matthew had a large stable block, which since the 1920s has been the golf clubhouse. He had some model cottages for his workers, a large laundry block, a fishpond with a boathouse, a formal garden with a fountain centrepiece, a skating pond with an island and, of course, an icehouse.

“There was not a lot to see when I last went down to have a look,” says Phil. “Until 20 years ago, the icehouse had been for probably a century at least a septic tank, so it was not a particularly pleasant place to visit.”

Poor icehouse!

OUR articles made Julian Goodwill realise that he and his father had come across an icehouse beside a public footpath while out walking their dog on the outskirts of Durham.

This icehouse is in a very curious location, just off the A690, on the northern edge of the Ramside Hall estate.

Ramside Hall was built by Sunderland mineowner Thomas Pemberton in 1820, towards the end of the icehouse craze. Pemberton called his property Belmont Hall because, like Beau Repaire and Bearpark on the other side of the city, it sounds attractively French and redolent of a lofty location.

The reality was that the hall was surrounded by coalmines, wagonways and railways.

For example, the icehouse was next to a farmhouse called The Rift which had Belmont Colliery as an immediate neighbour. The colliery operated from 1836 into the 1870s. There used to be a terrace of houses and a pub, the Belmont Tavern, inside the colliery compound, but all of them have gone now, as the area has gone back to nature and golf.

It is too much to hope that the icehouse was connected to the Tavern so that the miners could involve a chilled drink at the end of a gruelling shift, so it must have been connected with Belmont Hall.

If you have any more information about The Rift, we’d love to hear it.

MEMORIES 469 suggested there had been an icehouse in the grounds of Burn Hall, at Sunderland Bridge, which was built for the Salvin family by Durham architect Ignatius Bonomi.

Another correspondent with a punter in his hand, Clive Wilkinson, reports: “It is still there, beside the River Browney on a tight bend, opposite the third tee of Durham City Golf Course which is on the other side of the river.”

THERE was also an icehouse at Elemore Hall, near Pittington. The hall was built about 1750 by George Baker, son of the Durham City MP, who was a man of extravagant habits. It was built of sandstone quarried on the estate, and once the hall was complete, George had an icehouse built inside the quarry.

The icehouse was still there during the Second World War when it was used as an air raid shelter, but is it still there now that the hall houses a special school?

HAYDN NEAL in Sedgefield reports that there were two icehouses in the grounds of Wynyard Hall, although only one can now be found.

Wynyard was built for the Londonderrys in the 1820s, and the Londonderrys obviously liked their ice. At their other Durham residence of Seaham Hall, old maps show an Icehouse Dene and an Icehouse Bank which were just beneath the kitchen gardens.

AND to recap, in previous Memories we’ve had reports of four icehouses built into the rock on which the city of Durham stands, the best preserved being Shipperdson’s icehouse near the Count’s House. We’ve found icehouses at Gibside and the Hermitage at Chester-le-Street, while at Darlington there were icehouses attached to the homes of Pierremont, Blackwell Grange, Polam Hall and Blackwell Hill, which had two.

Finally, in Hurworth, there’s the remains of Hurworth House’s icehouse dug into the steep bank of the Tees just off the village green.

Are there any more? Please email chris.lloyd@nne.co.uk if you have any hot icehouse news.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here