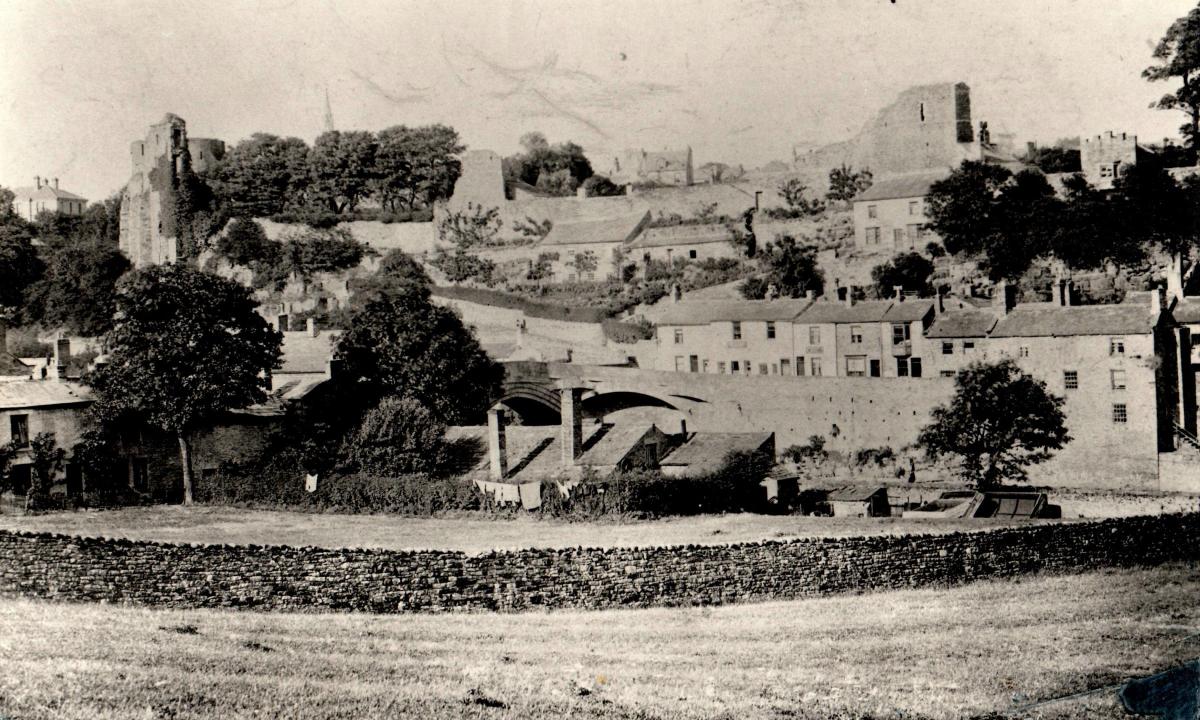

WHEN Dominic Cummings drove down The Bank in Barnard Castle towards the River Tees in the height of the coronavirus lockdown of 2020, if his eyes had been working extremely well, he could have peered through the mists of time to when a pandemic last catapulted the riverside streets into the headlines.

It was September 1849, and the view of cholera-ravaged Thorngate and Bridgegate would not have tempted him to tarry awhile as he did during the corona-stricken days of April 2020.

Instead of seeing the wooded riverbank beneath the castle full of beautiful bluebells, he would have seen burning bonfires as attempts were made to fumigate the unhealthy atmosphere and to mask the stench of death.

There would have been traffic on the roads back then: an almost constant procession of funerals making their way up from the riverside slums to St Mary’s Church were, three or four at a time, the bodies were buried in a plague pit which today is marked by a stone cross.

In eight weeks in the autumn of 1849, 377 people in Barney became infected with cholera of which 145 died.

Nearly all of those cases were in the town’s industrial quarter: down The Bank and along the riverside. In those days, both sides of Bridgegate were crammed with houses, yards and mills, where people lived cheek-by-jowl with pigs, cattle and hens amid slaughterhouses, offal piles and dung heaps – in fact, a person’s collection of dung was often admired because it indicated he was dedicated to using it as fertiliser on his allotment.

And that’s not to mention the privy pits of the humans and the tanning pits of the leather industry, both of which were filled with stale urine – there were 35 pits in the Bridgegate tannery alone.

And that’s not to mention the lack of fresh water or sewerage system – in Kirtleys Yard on The Bank, a cellar had been converted into a cesspit in which there was a six inch carpet of sewage with people living on the floor above.

And that’s not to mention the chronic overcrowding: in one house in Swinburnes Yard there lived 32 people. Nearly all of them contracted the disease and 15 of them died.

Cholera was not new – especially not to the North-East. Troop and trade movements had brought it to Europe from India, and it arrived in Britain in late 1831 when a ship from the Baltic docked in Sunderland. About 215 people died on Wearside, and for decades afterwards, the disease swept in waves across the continent.

Understandably, this invisible killer was greatly feared. It struck with lethal speed: within 12 hours of infection, a profound bout of diarrhoea brought a victim to death’s door, not helped by medical advice that advised against replacing the lost fluids.

It was, though, considered a disease of towns, where populations were dense, and also of the middle classes who could afford to move about.

But then, in August 1849, it hit rural Barnard Castle. The town had found a niche as a carpet manufacturer, producing patterned, reversible cloths that inexpensively brightened middle class houses across the country. Many of the hundreds who worked in the water-powered mills lived in their shadow in appalling conditions.

One of the victims was John Pratt, who owned a carpet mill and was a member of the Sanitary Committee of the Board of Guardians which governed the town. He was “taken very ill, togther with his eldest daughter (Catherine, 14), on Sunday morning last, and ere the sun set of the same day they were both lifeless corpses, and on Monday were interred in one grave. The general gloom was increased by this sad calamity.”

Mr Pratt’s death resulted in the closure of his mill, which threw 300 people out of work – just as today, the economic crisis which engulfed the town was as great as the health crisis.

Barney gained a reputation as a “plague town”, and for months it was shunned by outsiders.

There were, though, people and institutions which tried to alleviate the suffering. The Darlington & Stockton Times had been founded in the town in 1847 by solicitor George Brown, who was an influential voice. The paper took a high-minded attitude to the people who lived in squalor with lax morals, but also published recipes for them in their hours of need, advising they adopt “a nutritious diet (clear of flatulent vegetables)”.

More practically, the Board of Guardians, which oversaw the running of the town, appointed seven medical men on four guineas a day to tackle the disease door to door. There are reports of them covering the fists with towels and breaking open windows to let a little air into the tenements.

All but two of them – Dr Edger and Mr CJ Cust – fell ill. “Their attendance at the couches of disease and death, day and night, has been most assiduous and faithful, and their marked humanity and kindness to patients and their families have gained them general esteem and affection,” said the D&S.

The real star was the curate-in-charge of the church, the Reverend George Dugard, who was constantly ministering to the sick, lighting fires, preparing food, starting a soup kitchen at his own expense, comforting the dying and burying the dead.

In its issue of October 6, 1849, the D&S felt able to call the “almost total disappearance of this malignant disease”, and it immediately began to look for a better future.

“The calamity which has befallen the people has awakened attention to the claims of the poor – to the wretchedness, the poverty, the miserable bedding and hovels,” it said.

“Gloomy – dismal indeed – has been the night of affliction and death, but “as darkness shows us worlds of light we never saw by day”, so has it been full of revelations pregnant with future good. We cannot dilate at present upon the multitudinous blessings which we reverently and solemnly believe will in Barnard Castle follow the career of the destroying angel, and remain to enrich and benefit us long after his victims have been forgotten.”

The paper was to an extent correct, because in July 1850, the town elected its first Board of Health – the third of its kind in the country – and the Rev Dugard, in recognition of his stalwart efforts, received the most votes. He quickly found himself being drawn out of the religious sphere and commenting on political matters, like how the wealthy should contribute to improve the lot of the poor.

Using the rates, the Board employed salaried officials, including an Inspector of Nuisances on £7-a-year, which did indeed start to tackle the root causes of the epidemic.

But the carpet industry in the town was finished, and the economic contagion encouraged the townspeople to push even more forcibly for a railway connection. It arrived from Darlington in 1856 to boost local trade.

In its post-pandemic issue of October 6, 1849, the D&S had great faith that the town had natural attributes that would help it to recover.

“Barnard Castle possesses great facilities for being made a delightful place,” it said. “Situate in one of the most romantic and enchanting districts in England – embosomed amidst the classic grounds of Rokeby, Brignall Banks, and Wycliffe, and the beautiful vales and ravines (consecrated by Saxon antiquity) of Thor’s gill, Friga’s dale, Balder’s dale and Lunedale, in the centre of a district where Tees flows amidst scenes almost unrivalled for their varied loveliness and romance, we know no town capable of being rendered a more agreeable place than this.”

Exactly the sort of place you’d love to escape to from the tedium of a lockdown so that your eyes could feast on the beauties of Teesdale – but you wouldn’t break the lockdown rules to do so, though, would you?

- For more on this 1849 epidemic, look out for Beverley Pitcher’s 2004 book, Barnard Castle and the Cholera Outbreak

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here