THIS elegant bell once belonged to Lady Sybil Eden.

It looks demure and chaste, the lady fully covered up in layers of skirts and dresses, until you turn it up and discover that the lady’s legs, without any knickers, are the clangers.

“I’m 83 and I got it when I was a few months old,” says Maurice Siddle, of Darlington. “It was Lady Sybil’s, and I got it to keep me quiet while my mum was working at Mainsforth Hall.”

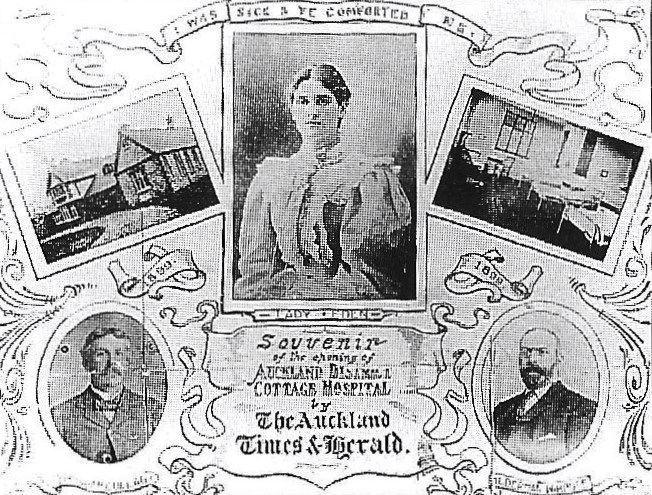

Lady Sybil featured in Memories 470. She lived at Windlestone Hall, near Rushyford, and she was the prime mover behind the creation of Bishop Auckland’s first public hospital.

She died almost exactly 75 years ago – on June 17, 1945 – at Windlestone Lodge. Her front page obituary in The Northern Echo said: “An outstanding figure in the public and social life of south-west Durham for the last 60 years, she took a very active interest in the welfare of the mining community, and it was largely due to her efforts that the Bishop Auckland Cottage Hospital was built in 1896 because she felt the pressing need of a hospital which could provide immediate treatment for the victims of colliery accidents.”

The paper said how she was involved with church, nursing, welfare and training organisations, plus the societies for the prevention of cruelty to children and animals. She was an all round good egg.

Except…

She was only 19 when she married Sir William Eden in 1886, and was regarded as one of the great beauties of her age. She was “almost the last remaining example of the Madonna type of loveliness now so rarely seen,” according to Woman magazine in 1893.

She bore Sir William four sons and one daughter. The eldest and youngest son were killed during the First World War, and there was a lot of doubt about whether the third son, Anthony, was really Sir William’s. That third son, of course, became Prime Minister of Great Britain in April 1955.

Sir William died in 1915, and Lady Sybil lived increasingly lavishly. She was adored in south Durham for her largesse – but the people didn’t see that she was frittering away the family fortune, selling or pawning the family treasures and borrowing from Durham moneylenders who charged her enormous interest rates.

In 1919, her surviving sons, Sir Timothy and Anthony, had to bale her out to the tune of £20,000, and in 1936 they were compelled to sell Windlestone Hall because of the debts.

Anthony once wrote of his mother: “I believe her to be a very unscrupulous and untruthful person.”

MEANWHILE – and this could make a good plot for Downton Abbey – a few miles north-west of Windlestone, another of Durham’s great families was coping with money issues and generational change.

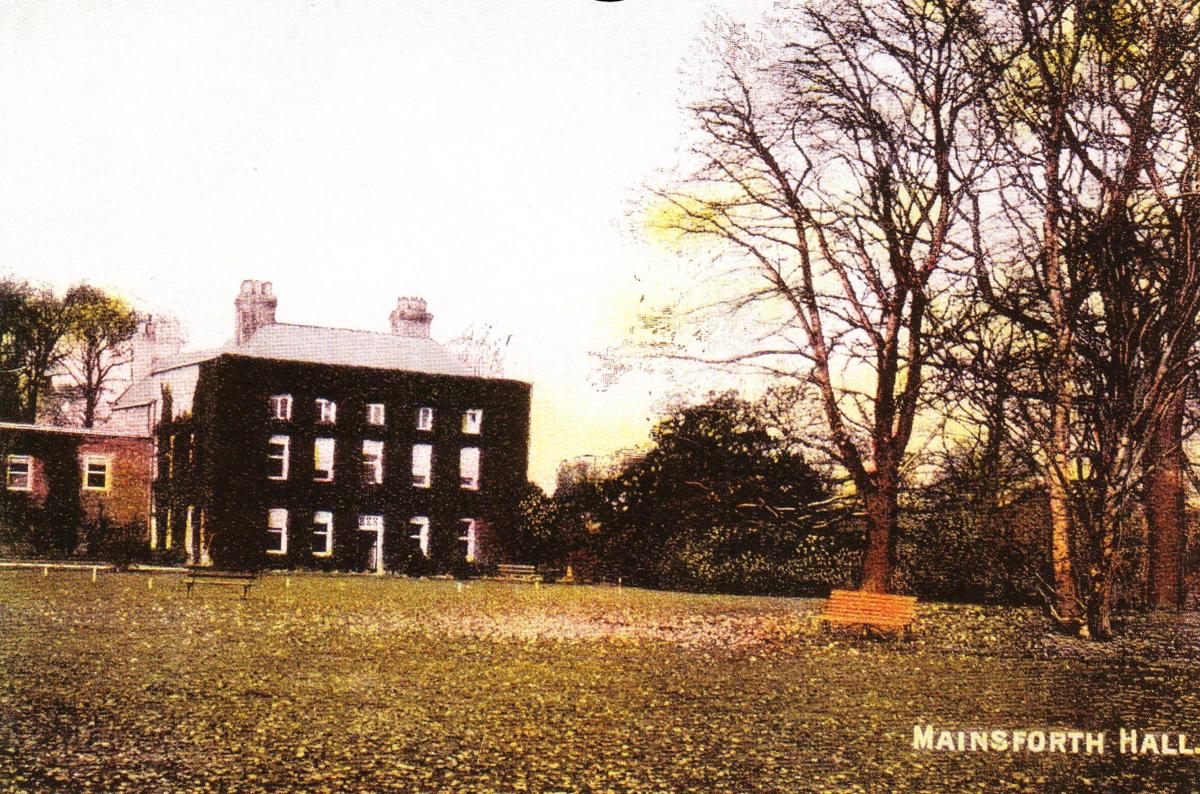

The Surtees family had built Mainsforth Hall in 1625 and rebuilt it in 1720. After the First World War, it was the home of Brigadier-General Sir Herbert Conyers Surtees and his wife, Madeleine, and their two daughters. Sir Herbert died in 1933, and Lady Madeleine lived on at the hall until her death in 1957 when Mainsforth was inherited by her grand-daughter, Virginia.

Virginia has a spectacular pedigree. She was the daughter of an American diplomat and the great-niece of the US publisher James Gordon Bennett whose stories and exploits were so outlandish, they gave rise to the exclamation “Gordon Bennett!”

Virginia was born in Beijing, became a diplomat’s wife, but while on a diplomatic visit to a hospital in Rome, fell in love with an airline executive who’d been badly injured. After divorcing the diplomat, she married the airline man but that marriage suffered so much turbulence, it finished after two years.

She then devoted her time to researching art history in London.

On inheriting Mainsforth, she changed her surname to Surtees.

She had Mainsforth Hall demolished in 1962, and now only its gateposts remind us where it had stood for nearly 400 years.

She died in London, aged 100, in 2017 – but never forgot her Durham past. The Durham County Record Office has a large number of her papers and memories which she sent up. Sometimes she even phoned up to tell the staff of her times at Mainsforth.

One such memory she phoned with tells of a dinner party sometime after 1933 at Mainsforth at which Lady Eden was present.

Virginia remembered there was one of those curious moments where the whole room falls silent when someone is saying something embarrassing. A male guest asked Lady Eden: “And what is charm?”

And Lady Eden replied: “Charm? That is what I’ve got.”

Virginia finished her memory with the pithy comment: “That is all I remember, but it must have been a laid on charm – vanity.”

So this tells us two things. Firstly, it offers an insight into the haughty Lady Sybil’s character, and, secondly, it shows us that she attended a dinner party on at least one occasion at Mainsforth Hall in the mid to late 1930s.

Perhaps it was at that dinner party when Maurice Siddle’s mother, Edith, was working. Perhaps there had been a family crisis at the Siddle home in Bishop Middleham, and Edith had had to bring her newborn baby into work. Perhaps she put him out of the way, in the kitchen, where, perhaps, he immediately kicked up a racket with his crying. Perhaps the only thing that could placate him was the bell that Lady Sybil always carried with her to tinkle for her servants’ attention.

The skirts, the legs, the smooth cool brass and the pretty tinkle would keep a baby quiet – and, 83 years later, Maurice still has Lady Sybil’s bell.

WHEN Lady Sybil died 75 years ago, her eldest son, Sir Timothy, presented a bust of her to go in the entrance of the Lady Eden Hospital in Cockton Hill – it was opposite was now Bishop Auckland General Hospital (BAGH).

In 1990, the cottage hospital was converted into a psychiatric unit, and Lady Eden’s bust went down to Tindale Crescent Hospital, which had opened in 1900 in the middle of nowhere for people with infectious diseases.

It was one of 28 such hospitals in the county, and it had separate wards for cases of diphtheria, scarlet fever and enteric fever. Patients’ clothes were fumigated by a steam disinfector; parents were only allowed to see their children through windows, and it had its own ambulance and mortuary out the back.

In 1955, the last TB case was transferred to Holywood Hall in Wolsingham, and Tindale became a geriatric hospital.

“We put the bust outside a ward which we renamed Lady Eden Ward, and there were always flowers put round her,” says Nellie Bowser. “We always looked after her and she was affectionately known as Sybil.”

Nellie was a stalwart of the Tinsdale Hospital Helpers which, through their garden parties and events, raised £100,000 over 50 years to provide comforts for the patients. For her efforts Nellie, and her friend and fellow Helper Mary Hodgson, were awarded MBEs.

But Tindale closed in 2002 when BAGH opened.

“The last I heard was that Sybil was down at the new hospital,” says Nellie. “We’d been promised that Ward 6 would be named the Tindale Unit, although the authorities weren’t very enthusiastic about it, and it was suggested that she should go in the entrance to the unit, which I thought was a good idea.

“Then I made some inquiries and she had somehow disappeared.”

The next Nellie knew was three weeks ago when Memories 470 had a picture of Sybil’s bust appearing on a 2014 edition of Antiques Roadshow filmed at Durham Cathedral. It seems that the NHS bigwigs had sold Sybil in 2009 – not that, in the great scheme of things, she was worth very much: the Roadshow valuers reckoned between £1,500 and £2,000.

Does anyone know where Sybil is now?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here