What was the ending to the love story told in our VE Day supplement? The events of exactly 80 years ago, and our army of researchers, provide some clues.

May 20, 1940

6am. Railway embankment overlooking “Fishaw village”.

I could see the boys fighting like hell with tanks all around them simply going over the men, and what a terrible sight. A German machine gun opened out on my left flank on us - did he do his stuff. He simply raked us with machine gun fire and to complete his work, 2 tanks came up behind us and positioned themselves about 20 yards away. They opened out with their 2lb shells and simply blasted us out of the embankment.

We were surrounded and within a minute or two I had 14 killed and 16 wounded. To hear those lads moaning made me feel rather sick. I myself didn’t feel too grand, having been hit in the foot. When hit, I rolled down the bank and just missed being blown to hell by a tank shell, it burst just where I had been lying. Thank God for that.

What was left of us were signalled by the German tank commander to group together in the field. Sgt Rutherford carried me over on his back and after cutting off my boot, laid me down among the rest of the boys. Lt Noble gave me a drink of rum and then Jerry searched us, going through our pockets and taking all he fancied from us.

We were told to sit close together and really we expected to be wiped out. We were then told to stand up, excepting those wounded. Sgt Bailes (badly wounded) Sgt Brockelbank and myself were put on the front of a tank and taken away. I assure you this, Jerry didn’t have any feelings. He went hell for leather giving us a hectic time. It took all our strength to keep on this tank, to fall off would mean certain death.

Down the road he went towards “Fishaw Village” and it was a very sad sight, seeing our dead comrades lying all over the field, on each side of the road. What a sacrifice, but we did our best to stop the Hun.

We passed a barn. It was an inferno, blazing like hell, and some of our boys are inside, burnt to death. We saw at least 2 bodies, half in and half out of the barn door, burnt black. God what a sight.

THESE edited words are from the diary of Company Sergeant Major Charles Baggs, and they describe one of the darkest days in North-East military history which occurred 80 years ago this week.

CSM Baggs was in charge of the 1st Tyneside Scottish, a regiment that had been recruited from the north of County Durham and which started out as the 12th Durham Light Infantry.

On that dreadful day, it was fighting alongside the 11th DLI, which had been recruited from Durham City and Chester-le-Street and included Pte John Cook whose love letters featured in our VE Day supplement. With 11DLI was 10 DLI, whose members came largely from south Durham towns like Bishop Auckland, Crook and Spennymoor.

The untrained and ill-equipped Durhams had been sent a month earlier into northern France as part of the British Expeditionary Force. Armed largely with First World War rifles and without proper communications equipment, they came up against a surprisingly agile German force.

On May 19, 1940, the regiments got the orders to withdraw back towards the coast, but because they lacked proper transport, they had to do so on foot. And the Germans were hot on their tails.

CSM Baggs, from Gateshead who had fought with the DLI in the First World War, wrote of the panicked retreat: “German aircraft (were) always giving us a reminder that we were being followed. Marched all day with no food and it is really warm. Boys getting weary and we all wonder where our artillery is, not a single gun, and not an RAF plane to give us a bit support. ‘Where the hell are we going’, everyone asks, but believe me, no one knows anything. We are just moving, not knowing where we are going and what to expect.”

The following morning, the 11DLI war diary records: “Without warning, a column of enemy Armoured Fighting Vehicles was met outside Wancourt. The tanks opened fire with their machine guns, and the Commanding Officer’s truck and its passengers were captured and all four men became Prisoners of War.”

To the enormous surprise of the British, the Germans had brought up three columns of light tanks, led by General Erwin Rommel, and backed up by Stuka divebombers, they ambushed the foot weary Durhams.

The Tyneside Scottish, bringing up the rear, were hit hardest, as CSM Baggs’ diary records. In an hour, the regiment lost 134 men, including Piper L-Cpl Frederick Laidler of Gosforth, 20. His nephew, guitarist Mark Knopfler has dedicated a song to him called Piper to the End.

The piper lies in Bucquoy Road Cemetery in the village of Ficheux – or “Fishaw” as CSM Baggs called it – alongside scores of Durhams who fell with him.

They rearguard action held the Germans up for about five hours, and allowed their fellows to begin the 60 mile trek northwards towards Calais and Dunkirk.

But the ambush had broken the three regiments into small groups, each one desperately trying to make its way to safety, and all vulnerable to being picked off by the enemy. Our VE Day supplement told how Pte John Cook, from Sherburn Hill, and four colleagues holed up for the night of May 22-23 in a farmer’s “roulotte”, or trailer, near Enquin-les-Mines, about 25 miles from the coast.

They had acquired a stray dog as a companion but, overnight, its barking betrayed their presence to the enemy and next morning there was a gunfight: two Durhams were killed, a third was injured and two, including Pte Cook, were captured. He left behind in the roulotte his last letters from home, including two from his sweetheart, Vi, of Sherburn Road.

Those men from the three regiments who still had their lives and their liberty trickled into Dunkirk from May 29 to 31, made it onto the little boats and bobbed back to Blighty.

Then the shocking headcount began.

10DLI had set out a month earlier with 28 officers and 621 men. Only 18 officers and 330 men came back.

Out of 11DLI’s 800 starters, only 200 survived, and out of the Tyneside Scottish’s 800, just 130 got back.

NOT all of the missing were dead. CSM Baggs, for example, was sent to a Prisoner of War camp in Poland, and after the war returned to Gateshead where he died in 1968.

Pte Cook ended up in Oflag IX-A, a camp inside Spangenberg Castle in Germany, and he too returned to the UK after the war.

In 1945, French police found the letters in the roulotte and saved them in Enquin-les-Mines town hall where they have recently been rediscovered by researcher Gregory Celerse.

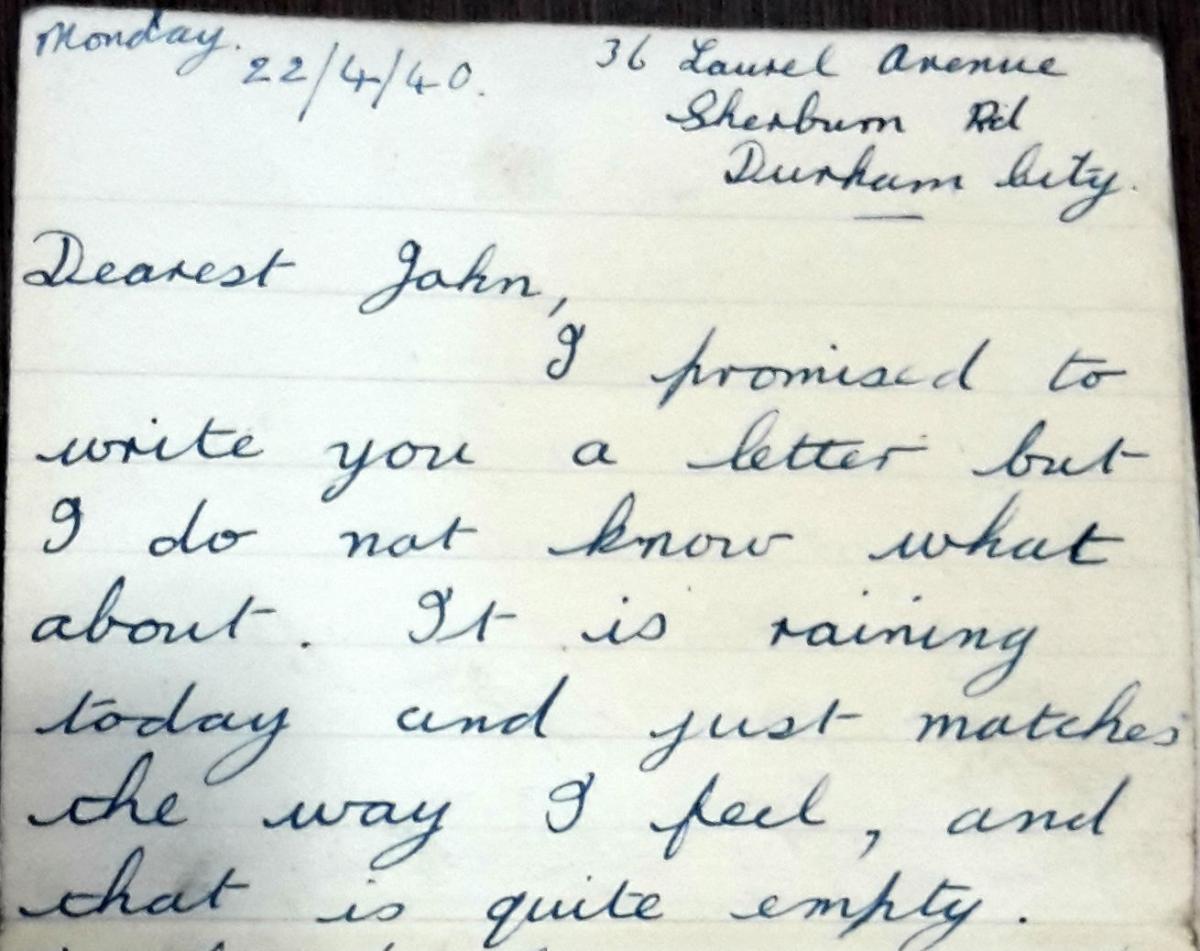

The letters reveal that on his last night in Durham, Pte Cook had proposed to Vi, but that she turned him down – because she had a secret she dare not reveal face-to-face. In her first letter, she tells him she has a two-year-old son from a previous relationship, and she pleads with him not to let it get in the way of their happiness.

From her second letter, it is obvious that he has written back saying he still loves her.

But then, with Pte Cook taken off as a PoW, the story went cold, leaving us wondering whether there was a happy ending, whether he and Vi were reunited at the end of the war.

We’ve had a great response.

For example, Billy Mollon in Durham City said: “My father, Harold, and my uncle Jack were also in the 11 DLI and would at least have seen John at the time. Luckily, they both made it back from Dunkirk and uncle Jack later was awarded the Military Medal after D-Day for rescuing two soldiers who had lost a leg each in a minefield.”

We are hugely grateful to all the people who have undertaken research on our story. We are also acutely aware that close relatives of the characters in it are probably still alive.

We now know that Vi’s full name was Violet Cranston, born August 17, 1913, at Shotley Bridge – and that her life was shaped by the DLI.

Andy Denholm of Evenwood said: “She was one of three siblings whose father, Andrew Cranston, died of wounds on January 18, 1917, while serving with the 2nd Durham Light Infantry. He is buried at Bethune Town Cemetery in northern France, which is just 35 miles away from where her John was captured.”

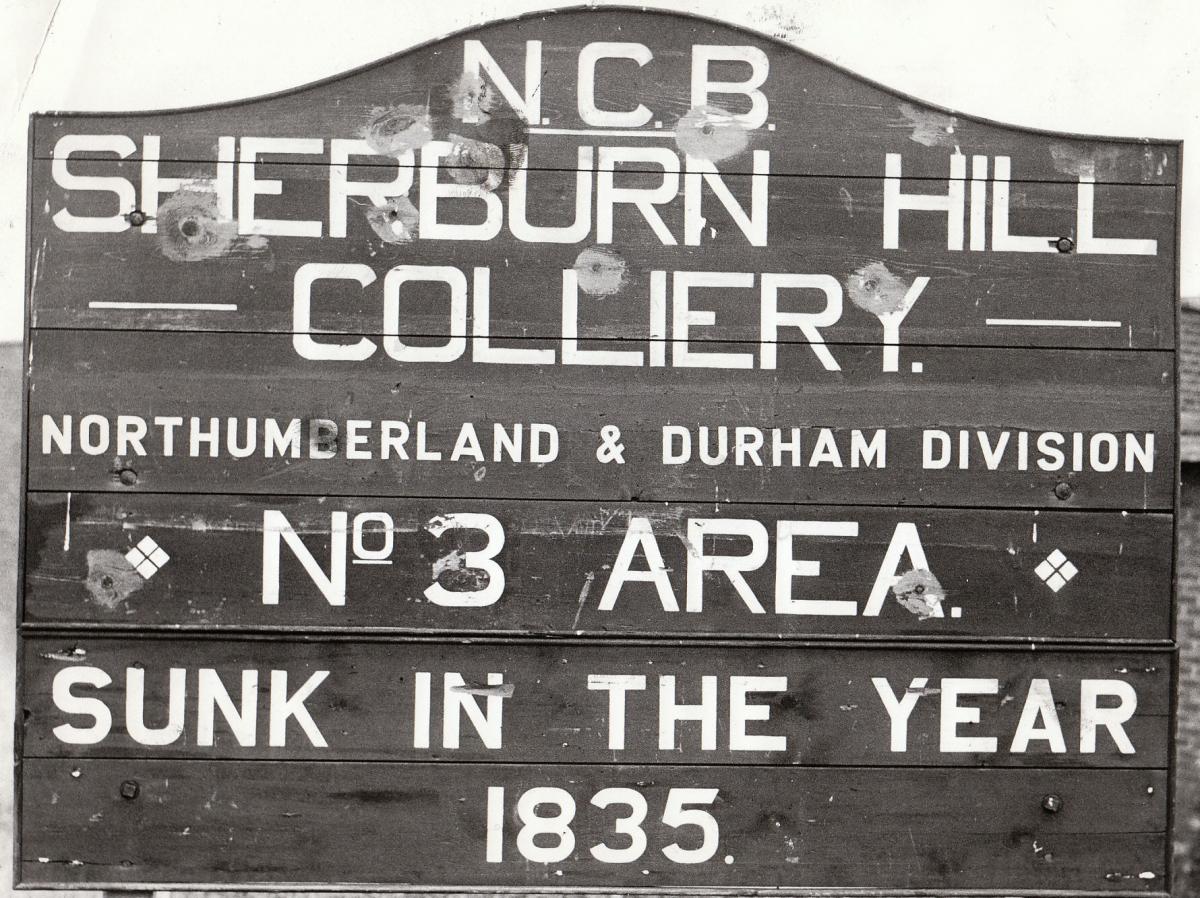

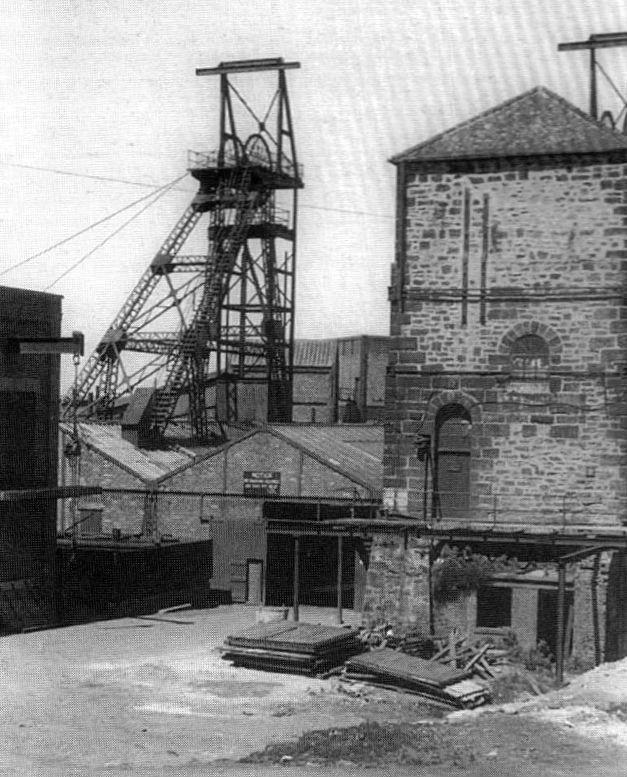

John Heslop and Katy Stoddard in Durham found that John’s mother’s maiden name had been Huddart, which he had as a middle name, and that he and his father, Joseph, were miners at Sherburn Hill Colliery.

But it would seem that when John was captured, his letters home stopped, and, seeing the carnage wreaked on his regiment, Vi may have come to the understandable conclusion that he, too, was dead. Aged 27, she’d been through the wringer: her father was killed when she was four; her first fiancé had died in motoring accident a fortnight before her wedding and then she discovered she was pregnant; and now her second fiancé was lost, like her father, on the killing fields of France.

The registers show that towards the end of 1940 she married another soldier in Aldershot and that the following year in Durham she gave birth to a son. We hope she found happiness.

We believe John died in Plymouth in 1983.

If you can add anything to our story, please email chris.lloyd@nne.co.uk

Much of today’s information and most of the picture come from John Dixon’s extraordinary website 70brigade.newmp.org.uk which chronicles the events of May 1940 in amazing detail, and features individual profiles of the hundreds of soldiers from the Durham regiments. If you have someone who was involved in this action, please email 70brigade@newmp.org.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel