Letters left when a Durham soldier was captured in France exactly 80 years ago have just been discovered. They give an amazing insight into a family separated by war and they tell of a powerful love story which has a major secret at its heart, as Chris Lloyd reports. But it is an unfinished love story – the letters cannot tell if it ended happily ever after once peace had come. Can you?

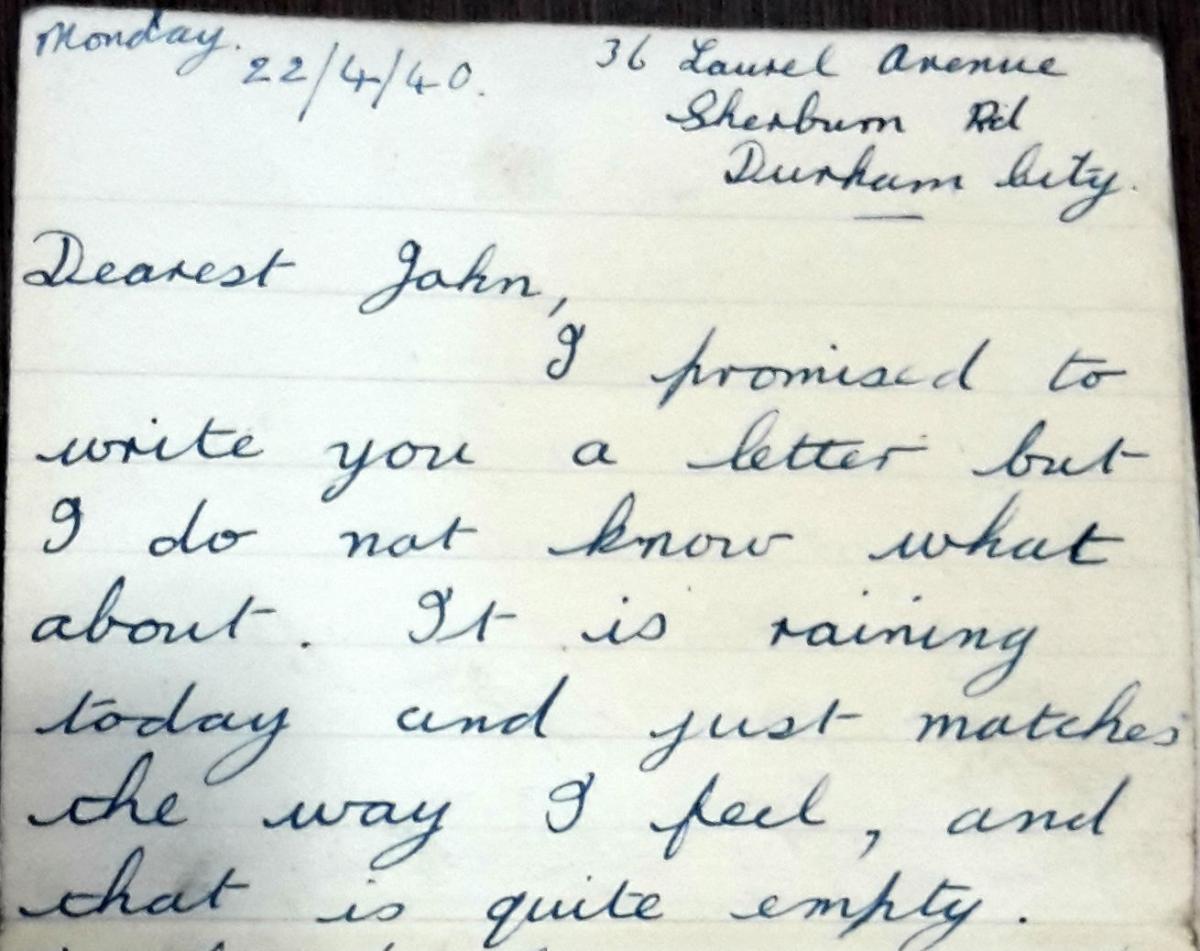

“It is raining today and it just matches the way I feel, and that is quite empty. I hated leaving you last night, but I took your photo and kept it under my pillow all night.”

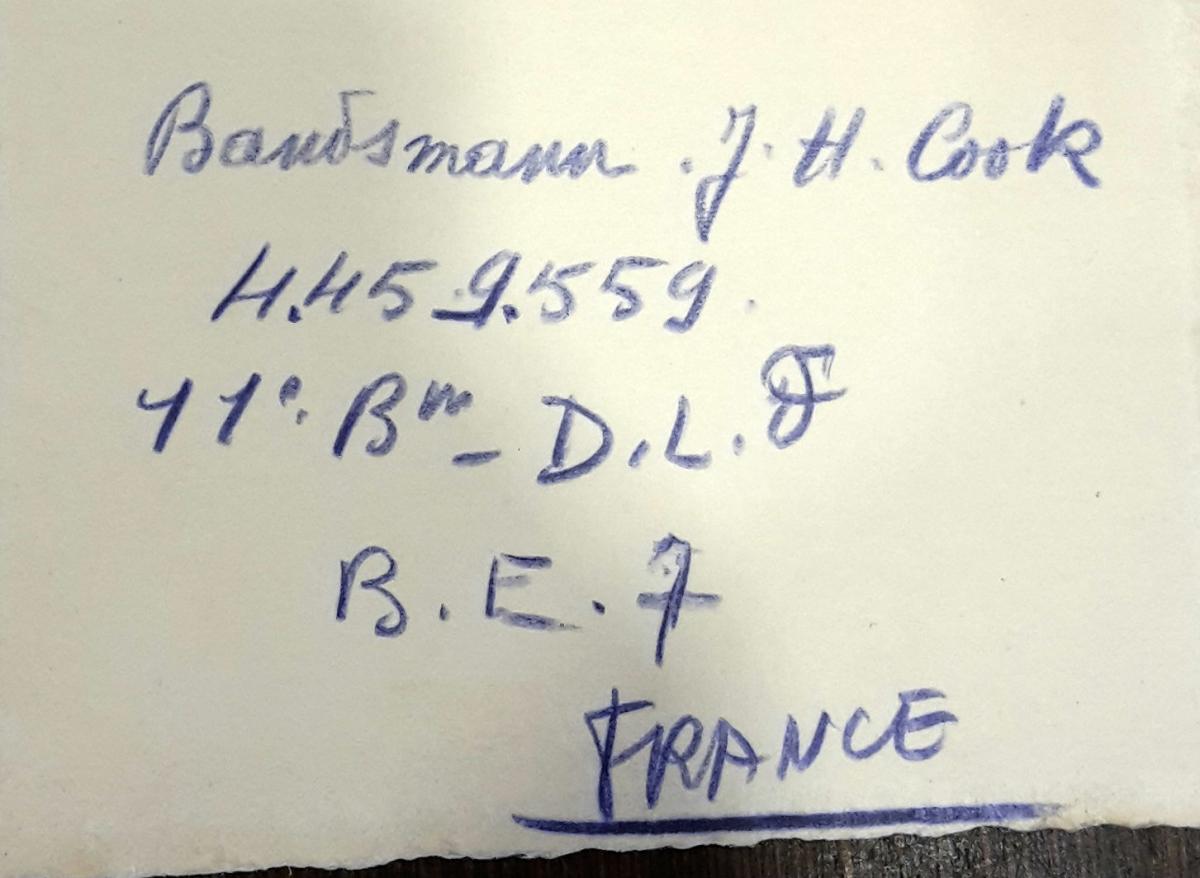

THIS is part of a letter that a young woman called Vi wrote from her home on the outskirts of Durham on April 22, 1940, to her new boyfriend, Private John Cook, who had left the previous day with the 11th Durham Light Infantry for northern France.

Although they had only just met, John had proposed to her that last night in Durham, but she turned him down because of a secret in her past – a secret that she would spill in another of her letters, leaving him with the emotional dilemma of whether he would still go through with the engagement.

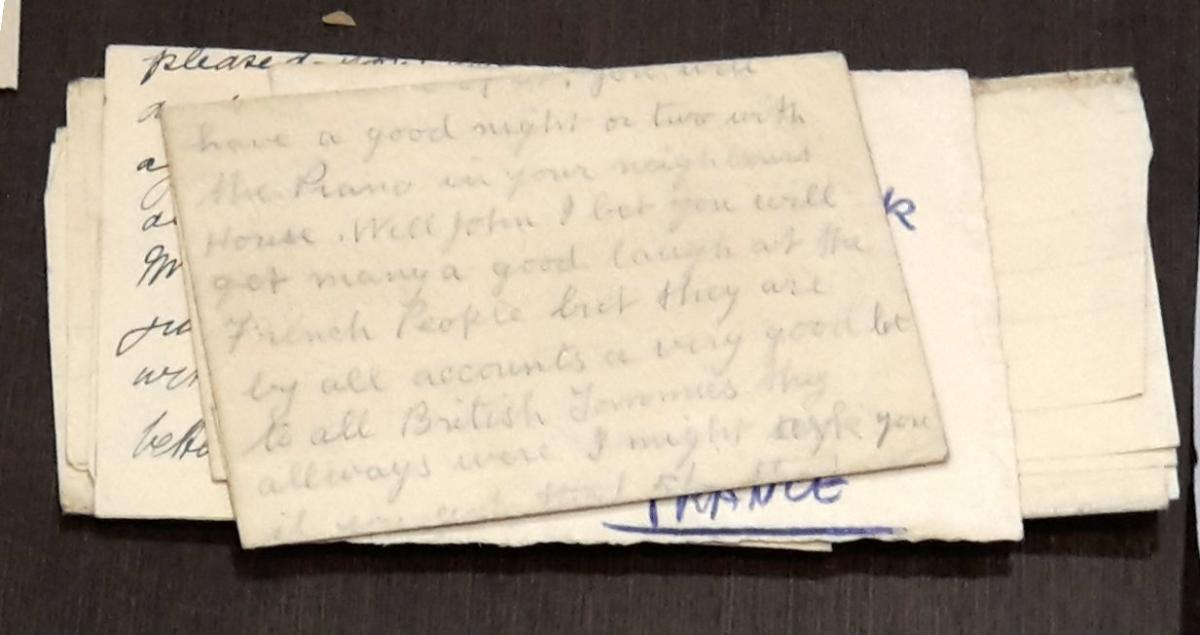

The letters were found after Pte Cook was one of five Durhams who were caught up in a gunfight in a French wood. As the Germans advanced unexpectedly rapidly 80 years ago, the five Durhams got split off from their battalion as they desperately retreated towards Dunkirk in hope of getting a boat back to Britain.

But, in the wood, they were betrayed by a barking dog on May 23, 1940, and were either killed or captured, with the letters left behind.

It is an amazing, heart-wrenching story, but it is a story missing an ending. What happened to Vi and John in peacetime?

The 11th Durham Light Infantry was formed hurriedly after the outbreak of the war, and sent quickly to northern France to join the British Expeditionary Force. The soldiers, including John, said their tearful goodbyes at Durham railway station and were in France within 36 hours; they had a rough two hour ride in a cattle truck into Normandy, and then a two mile walk to their campsite.

They were ill-equipped and under-trained. The idea was that they should get their boots on the ground in France and begin work on communication lines while continuing military training.

On May 5, having set up their camp, they began building an aerodrome, and they received their first letters from home.

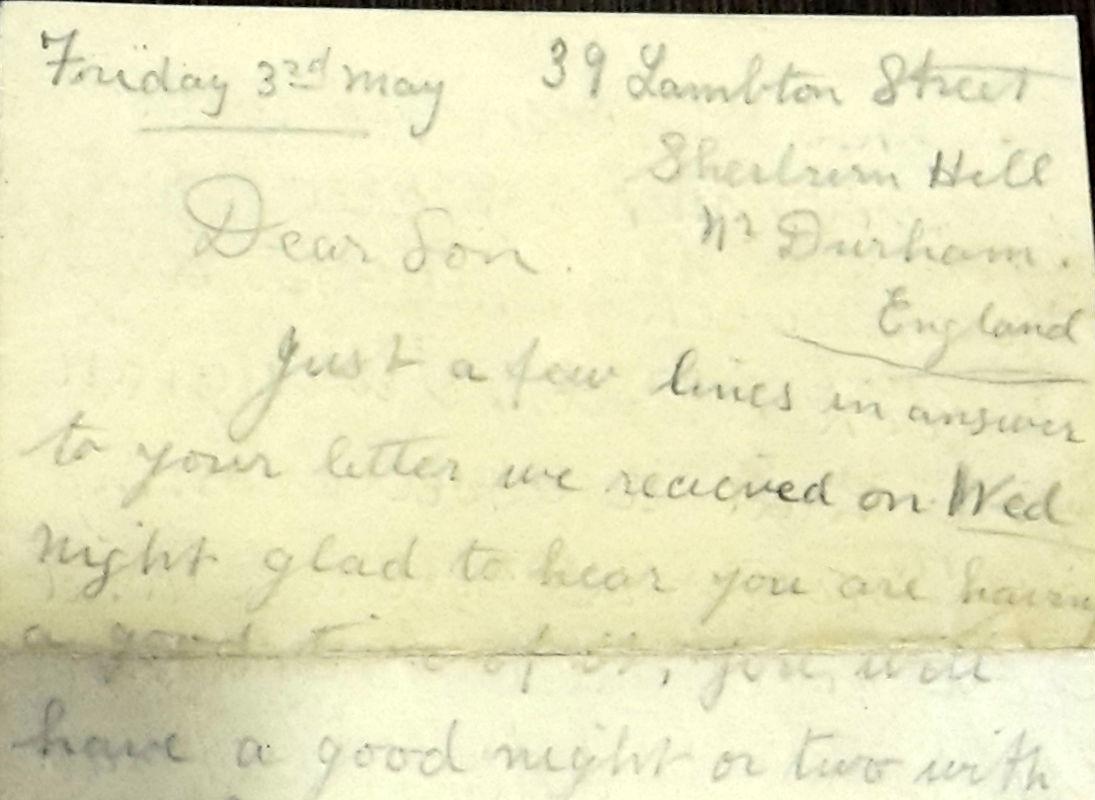

Pte Cook received letters from his parents, who lived at 39, Lambton Street, Sherburn Hill, a mining village a couple of miles east of Durham City, and from his aunts and uncles who lived at Shadforth, Blackhall Rocks and Littletown.

“It will not be long before this climax is over and that you are back to that dear little, sweet little, tumble down place of Sherburn Hill,” wrote the family in Littletown. “It isn’t much of a place but it’s there where our sweet home is and there is no place like home.”

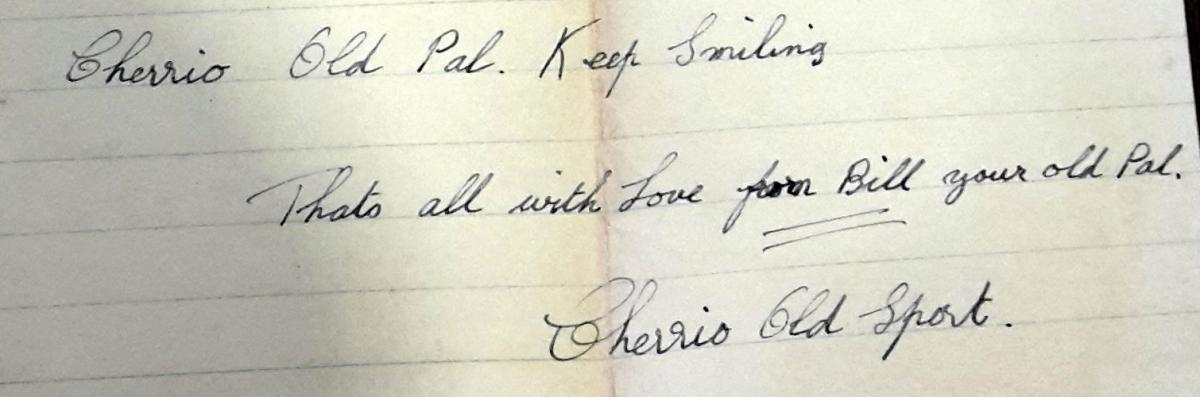

John’s father was a miner and writes as if John had some underground expertise as well – “I’ve got 2nd cavil on the long wall face,” he says – although John’s best pal, Bill “Digger” Hall of Shotton Colliery worked on the railway.

He wrote: “I had a dirty job last Saturday afternoon. One of our chaps who works at Sherburn station got killed with a passenger train. Both his feet were off and his head so you will have a bit idea what he was like.”

All the letters mention how John is a musician, obviously very good on the piano, accordion and trumpet, and some of the letter writers offer him pieces of advice. Mr R Ord, of 14 Miners Homes, Sherburn Hill, says that his wife, whom he refers to as “Mrs Ord”, has been to the pictures and chapel with John’s mother. He tells John: “Keep in with those about you. Keep a good character for it will carry you through.”

And all the letters mention John’s new girlfriend.

Digger Hall says: “You seem to be very much in love with Vi, hoping she is just as much in love with you. I would very much like to meet her…”

Mr Ord offers another piece of advice: “We do not know your young woman or else we would have kept in touch with her, but you must not leave your heart with the French girls. They say they are funny ones.”

And John’s father writes: “Mother says you have to send a photo of your young woman (Vi) to her so she can get a look at her features…”

There are two letters from Vi, the first written immediately after that tearful parting on that last night in Durham. She writes it from her home in rainlashed Laurel Avenue off the Sherburn Road in Durham City, less than three miles west of John’s parents’ home.

In it, she tells of the drama of their parting and the proposal. She says: “I hope you were not too disappointed last night when I refused you, but I would have been scared in case anything happened and you going away, but please believe me when I say I love you more than life itself so please come back to me, won’t you darling.”

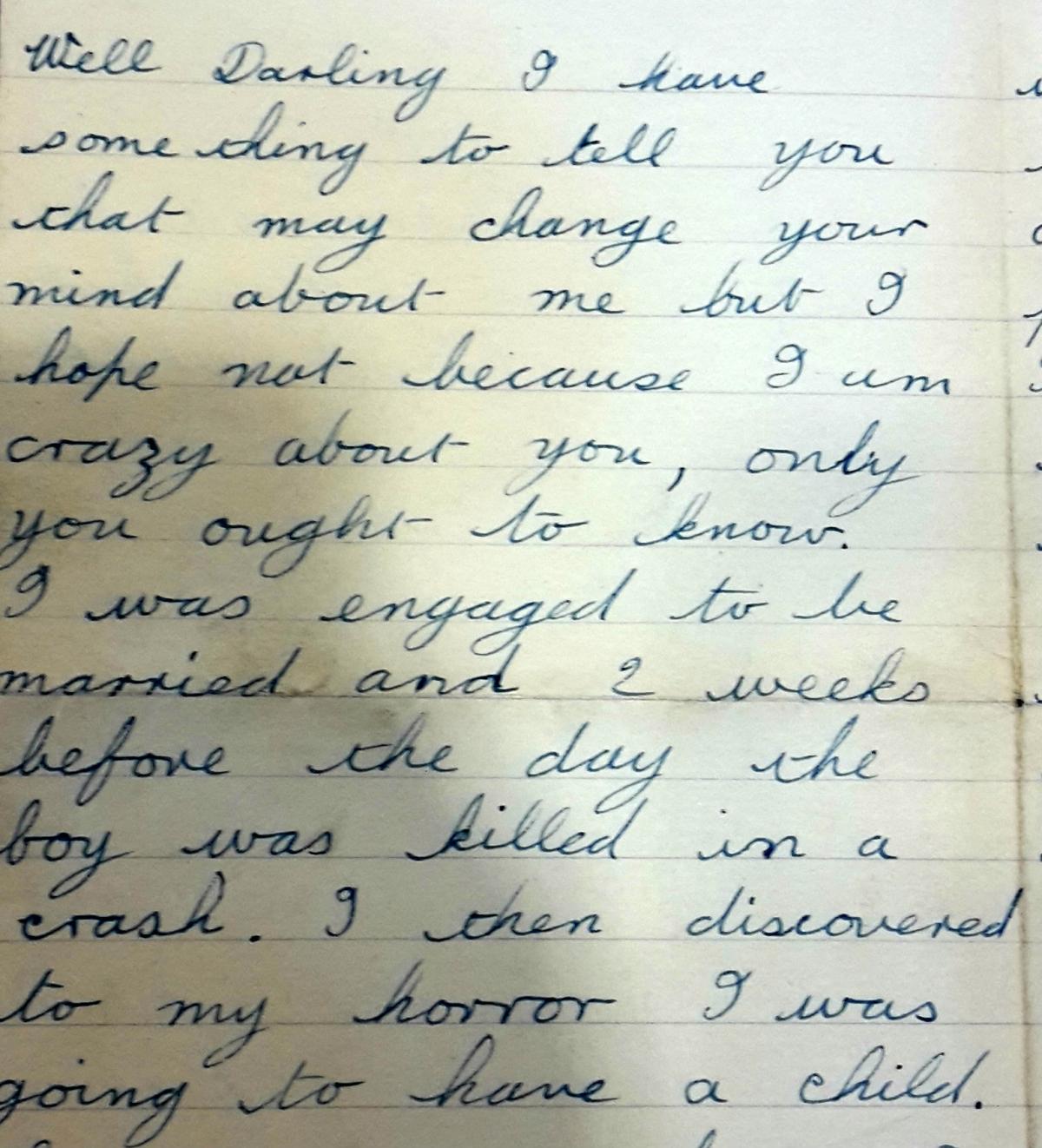

But then she continues: “Well, darling, I have something to tell you that may change your mind about me but I hope not because I am crazy about you, only you ought to know.

“I was engaged to be married and two weeks before the day the boy was killed in a crash. I then discovered to my horror I was going to have a child. So now you know I have a little boy 2½ years of age, but my mother looks after him.

“It is just as well in a way that I did not marry him, because now I realise I did not love him as I love you. Darling John, don’t let it make any difference as I adore you and if you throw me over I would break my heart.

“My mother thinks it is best to tell you now. I tried to last night only I did not want to spoil it. Please darling write back and say you still love me and that it makes no difference. I shall die if you say you hate me, but please write soon.”

What a bombshell to explode on your intended as he’s heading off to war! John must have received the letter when he arrived in France. Perhaps he read it as he was travelling in the cattle truck towards the enemy’s guns…

His reply arrived in Durham City on Saturday, May 4. How Vi’s heart must have pounded as she opened it in Laurel Avenue. Would it all be over?

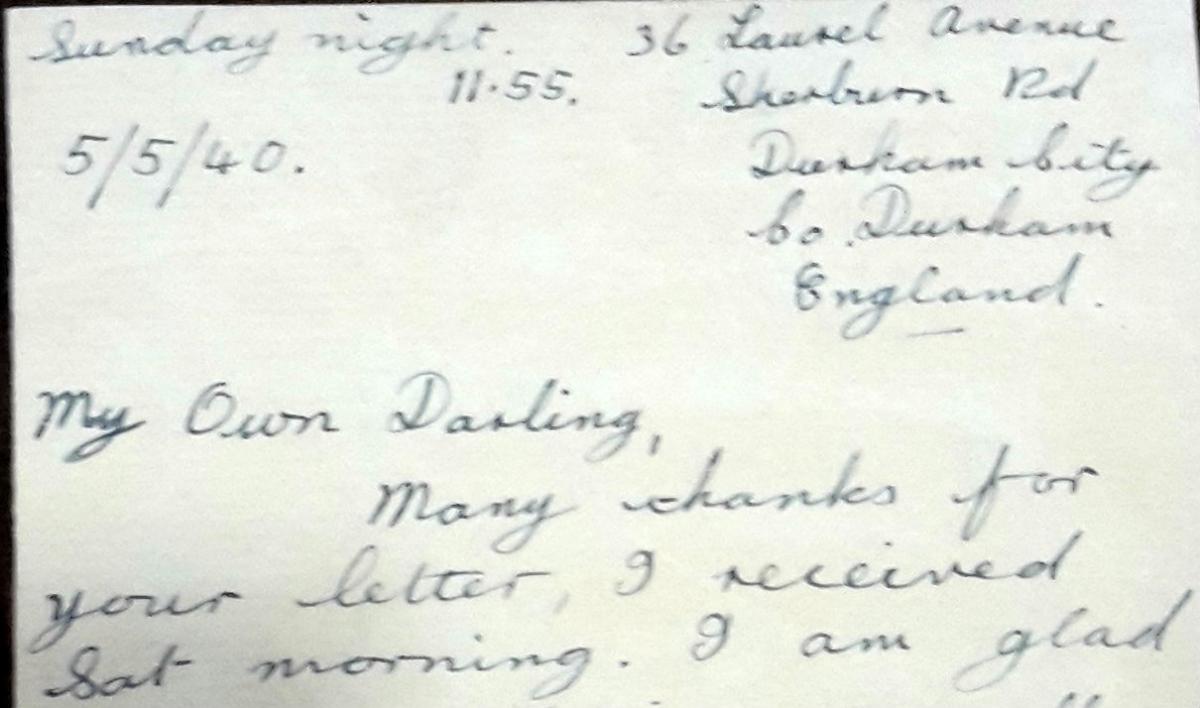

It wasn’t. John had accepted the existence of Vi’s young son, Brian, because in her reply – written at 11.55pm on May 5 – she said: “I am glad and happy it makes no difference to your love for me because I am crazy about you. Do you think your people might object to you having anything to do with me if they find out about Brian. I hope they don’t because it would break my heart to lose you. Promise to love me always.”

She continued: “You don’t need to ask me if I miss you, you know I do, terribly.

“I heard that song on the wireless the other night and it made me cry thinking of you, don’t you feel flattered, me crying over you. Ha! Ha!”

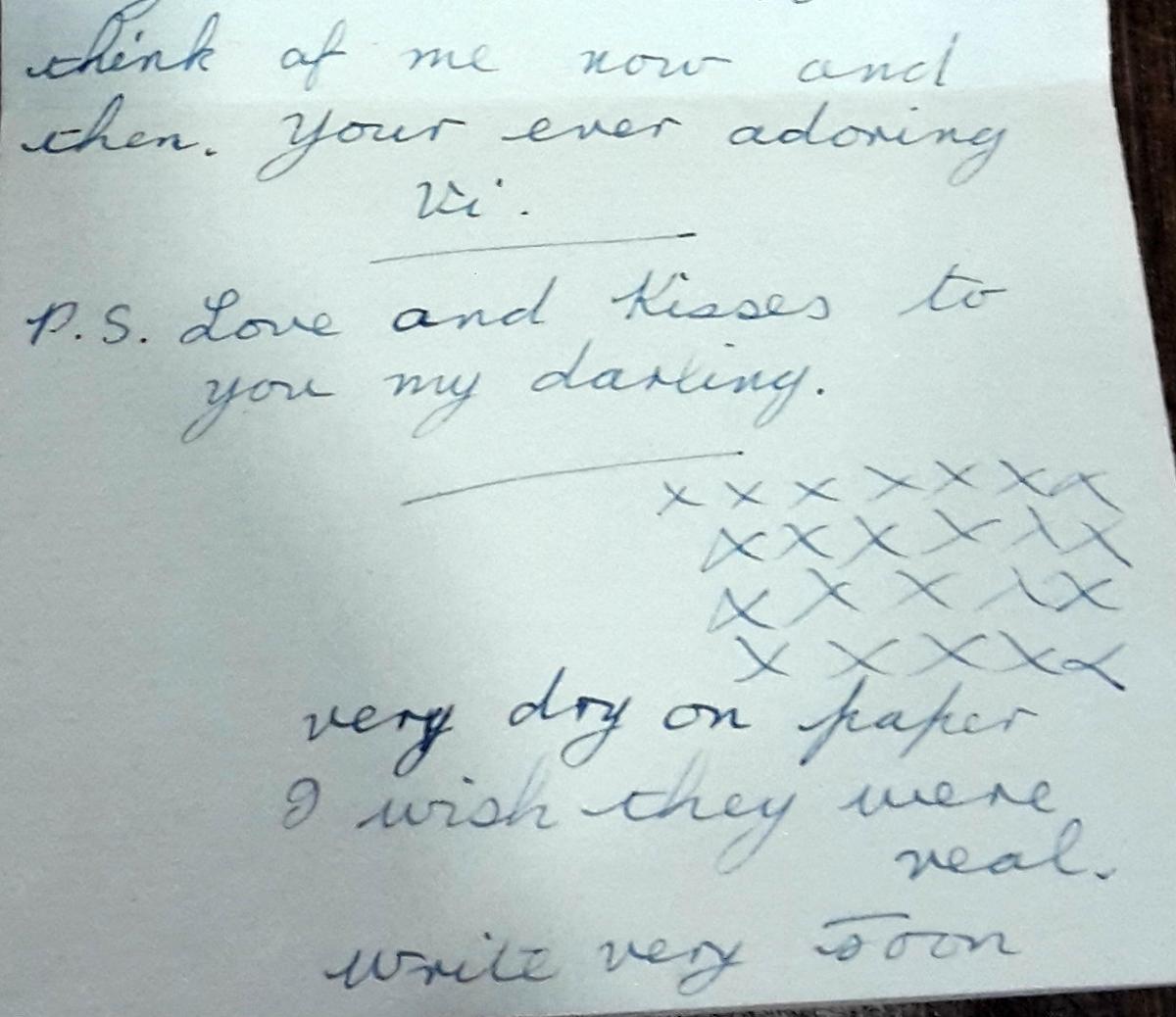

She ends the letter with an explosion of kisses, and the note: “Very dry on paper. I wish they were real.”

John would have received this second letter as 11DLI was coming under increasingly regular aerial attacks by the Germans.

On May 17, a fellow member of B-company, Pte Jack Collins, wrote in his diary: “Gerry advancing very fast, battalion moved off in a hurry and left 15 of us behind to look after the stores.”

John was among those 15.

They were now surrounded by the enemy. They could see the Germans stopping refugees’ cars and checking their passports.

On May 21, Pte Collins, whose diary was posted by his family in 2014 on the BBC People’s War site, wrote: “15 of us on run. Slept for 2 hours during night and bombed out at 5am. Millions of refugees on the road.”

John, with his letters in his backpack, was with Pte Collins. They were about 30 miles from the coast, and their best chance of rescue.

Pte Collins’ next entry reads: “22nd May — Walked for miles trying to get to Boulogne. Gerry all round. Feet sore and tired out. Slept in barn at night. Bitterly cold.”

John was still with him, but there were now probably only five or six of them left together. They holed up that night in a wood on a farm belonging to Alpert Panet near the village of Enquin-les-Mines, near St Omer – about 25 miles east of Boulogne. Monsieur Panet later said that they had sought sanctuary in his “roulotte”: a trailer or caravan.

He also remembered that the Durhams were accompanied by a dog that they had acquired along the way.

Surrounded, and not knowing what the dawn would bring, John must have spent that night looking through his letters, thinking about Vi and about how suddenly he was to become a father.

And the wretched dog must have been barking.

Its noise attracted the attention of a German patrol. As dawn broke, they came over to investigate...

What happened next was later the subject of a French police investigation into a possible war crime, but the engagement between the handful of Durhams in the roulotte and the German patrol ended at 7am on May 23, with two Durhams dead, a third badly injured in the foot, and two more – Pte Collins and Pte John Cook – captured.

That was the last that John saw of his letters.

“We were taken into a field, German soldiers speaking to us in French,” wrote Pte Collins in his diary. “At gun point we were made to dig some graves (thinking our end had come) but it was for the lads who had been killed. “God have mercy on us now”.”

John and Pte Collins were then sent by lorry and cattle train through the devastation of German-occupied northern Europe, going without food for more than a week, until they arrived at a Prisoner of War camp in Poland.

Without any news, and the wonders and horrors of the Dunkirk evacuation unfolding in the papers before their very eyes, the folks back home in Sherburn Hill must have been very anxious. Vi in Sherburn Road must have beside herself, crying herself to sleep every night with John’s photograph beneath her pillow.

Perhaps by mid-July 1940, news would have been filtering back that he was alive, but Vi would not have been able to see him for another five long years – he was one of the 13,000 British soldiers still being held prisoner on VE Day.

And this, at the moment, is where our war-torn story ends.

We don’t know want became of John and Vi – when he was released 75 years ago, did he return to her and did they live happily ever after?

We know the story, though, because after the war, French police investigated if the Germans had committed a war crime when two of the five Durhams were killed in the gunfight. They collected all the evidence from the farm, including the letters left in the roulotte, but found no case to answer, so the letters were placed in the archives in Enquin-les-Mines, where they have recently been discovered by historian Gregory Celerse.

“I would love to know what happened to Vi and John – I really hope that they got married in the end,” he says. “It would be great to make contact with any descendants, to show them the letters – I’m sure they’d be fascinated.

“I also want to put things right for the other two members of the Durham Light Infantry who were killed that day, because they are still listed as having no known grave and yet I believe I know where they were finally laid to rest.”

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission website simply says that Ptes Gribbin and Woods have their names inscribed on the Dunkirk memorial because the location of their last resting place is lost.

But in his evidence, farmer Panet, who has since died, said that a year after the engagement at the roulotte, the local people of Enquin-les-Mines reburied the two Durhams in the village churchyard where, it is believed, they lie to this day.

If you are related to any of the people in this story, we’d love to hear from you. Please email chris.lloyd@nne.co.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here