In association with

DURHAM COUNTY COUNCIL

WHILE the street parties were in full swing in streets festooned with bunting back home in Blighty, Victory in Europe was marked in a starkly contrasting way for many British soldiers serving in different parts of the world.

And the lads from the 113th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment Royal Artillery – many of whom were North-East born and bred – had perhaps the grimmest task of all around the time VE Day was celebrated back home.

It was their job to help clear the Belsen concentration camp, in northern Germany, where an estimated 50,000 lives – potentially many more – were cruelly taken by the Nazis.

The 113th LAA Regiment had been formed from the old 5th Battalion of the Durham Light Infantry, with many of its soldiers coming from West Hartlepool, Horden and Easington. It had been a particularly hard war for these men who had seen active service with their anti-aircraft guns from Normandy in June, 1944, to the crossing of the Rhine in March, 1945.

By April 18, after a drive of more than 200 miles in 22 hours – much of it through enemy territory – they arrived to be greeted by the horrors of Belsen. Their mission was to support the British Army in helping the living, burying the dead and preventing the spread of killer diseases.

The camp had been liberated three days earlier, with the discovery of thousands of sick and starving prisoners who were dying at a rate of 500 a day, mainly from typhus.

More than 15,000 bodies were buried in mass graves dug by bulldozers, while temporary hospitals were set up for those clinging to life and meals were prepared in five cook houses for 50,000 survivors.

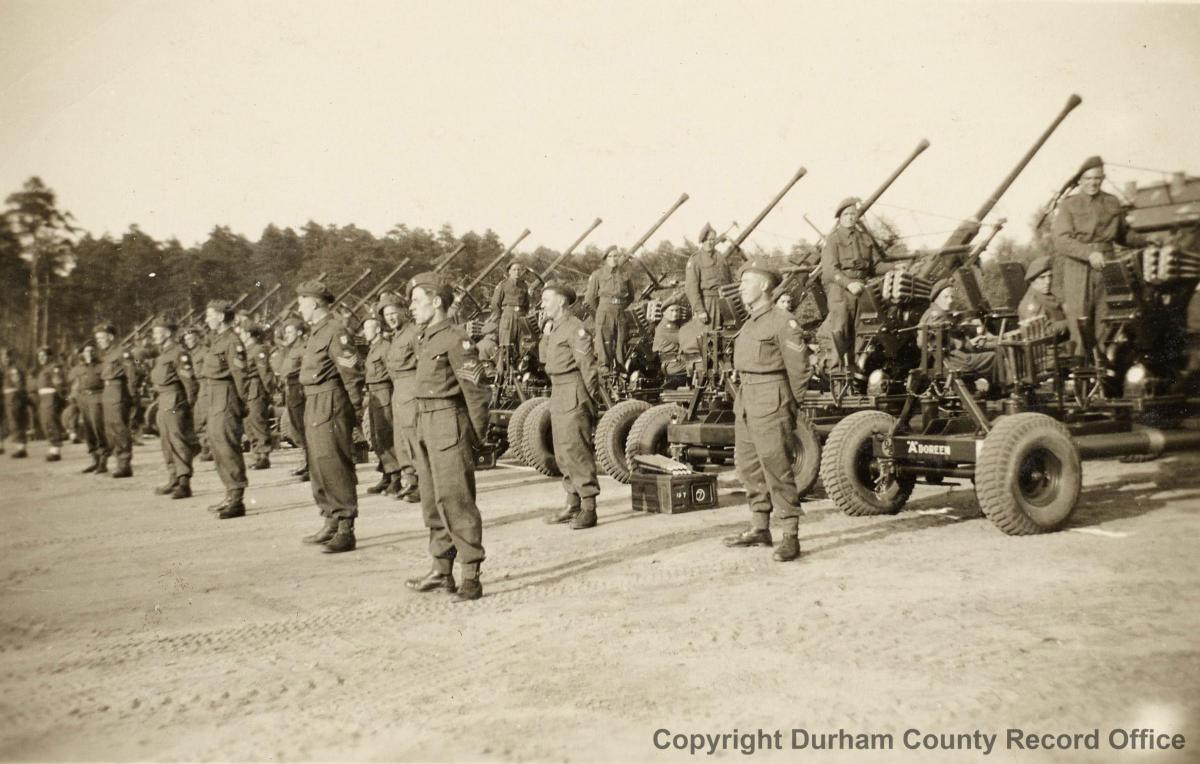

Having witnessed unforgettable sights, the men of the 113th Regiment marked VE Day by staging their own victory parade at their barracks at Hohne, just outside the concentration camp.

It was another two weeks before the last hut at Belsen had been burned to the ground and the soldiers of the 113th Regiment left for the Baltic coast.

Their reward was a well-earned two-week holiday but, for those lads from the North-East of England, the days before and after VE Day were associated with unimaginable memories that would last a lifetime.

Meanwhile, 5,000 miles away in the stifling heat of Burma, the war had also taken a heavy toll on the 2nd Battalion of the Durham Light Infantry.

The Burma campaign had been one of the longest fought by the British during the war. Far from Europe, and often overlooked in press reports, it became known as the Forgotten War and the troops who fought it, the Forgotten Army.

The 2nd Battalion had already suffered terrible losses in Belgium and France in the early stages of the war and, once rebuilt, it became part of the 14th Army in India in 1943.

After battling Japanese forces in the Arakan and at Kohima, in late 1944, the battalion joined the 14th Army’s advance towards Mandalay, where the Japanese Army in central Burma was to be destroyed.

Following the fall of Mandalay in early April 1945, the battalion’s next mission was to invade Rangoon. The Durham lads were flown back to India to train for the sea-borne invasion of the Burmese capital, but Rangoon was captured while the battalion was on-board ship, gearing up for the assault.

As German forces were surrendering in Europe on May 7 – the day before VE Day – the men from the North-East of England were given permission to leave the invasion ship to swim in the sea. Then, on VE Day itself, they were given two bottles of beer each to toast the victory. It was far from being chilled, but how good that beer must have tasted.

The end was finally in sight and the men began to dream of going home, but there was still work to do – Japan still had to be defeated.

After landing in Rangoon, the Durhams’ task was to patrol the city and nearby villages, collecting abandoned weapons and rooting out Japanese stragglers. To keep their minds off demobilisation, the British soldiers maintained their training but also played sports and enjoyed other forms of entertainment.

It was to be three more months before the first of the Durham soldiers were able to return home but, in the meantime, the hard-fought victory of the Allied forces in Burma was celebrated with a parade in Rangoon on June 15, 1945. The salute was taken by the Supreme Allied Commander, Louis Mountbatten, but it was literally a case of raining on the parade.

New uniforms had been issued, along with Burma Star ribbons, and the stage was set as the men left their barracks and assembled on a muddy field near the Shwedagon Pagoda. They waited two hours for Lord Mountbatten’s arrival, which coincided with the heavens opening...and when it rains in Burma, it really rains.

“It rained so hard, that within a couple of minutes, we looked as though we had just been dragged out of a river,” recalled one battalion member. “We marched past, shivering, half-blinded by the rain, our boots full of water – and we were told by spectators that we looked very nice.”

The wait continued until Japan surrendered on August 15 after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The war was over but the 2nd Battalion of the DLI did not hold a ceremony to mark the final victory. They simply prepared to go home to their beloved County Durham.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here