In association with

DURHAM COUNTY COUNCIL

WHEN the end of the war came for the battle-weary soldiers of the 9th Battalion of the Durham Light Infantry, it must have seemed surreal.

After six years of fierce fighting, it was over, and the Germans appeared to be as relieved about it as the British troops were. From being determined to shoot each other, desperate hands of conciliation were suddenly being offered by the enemy.

Private Jim Ratcliffe, who had served with C Company of the 9th Battalion, captured the mood when writing a vivid account of his experiences in the 1990s – 50 years after VE Day.

“A German soldier came down the road, waving his arms, carrying a Spandau (sub-machine gun) and shouting to us… ‘Tommy! War finished’. We all started shaking hands and congratulating each other at coming through it safely. Needless to say, the night was one to remember. Some of the rifle company lads got drunk with German troops who, the previous day, would have been trying to kill each other. I think everyone, including the German troops, were glad it was over.”

Before the war started the first recruits to the 9th Battalion had been Territorial volunteers – North-East lads with no experience of fighting – but they ended the six-year conflict with a proud, but exhausting, distinction.

The 9th Battalion, including a core of recruits from Gateshead, was the only unit of the Durham Light Infantry to see action from the Normandy beaches on D-Day, in June 1944, to the final defeat of Nazi Germany just under a year later.

From being new to war in 1939, the men from the North-East of England became veterans of battle. After years of hard fighting in France, North Africa and Sicily, they were chosen to land on the Normandy beaches in June 1944 as part of the 50th Northumbrian Division.

Then, having played their full part in D-Day, they endured months of bitter fighting across northern France and Belgium. While other DLI battalions were disbanded, the 9th was transferred to the 7th Armoured Division – the Desert Rats – to join the final push across the Rhine and on into Germany.

When the end came, the novices-turned-veterans of the 9th Battalion had earned their rest as much as any other soldiers engaged in World War Two.

Extracts from a newsletter printed at the DLI’s depot at Brancepeth Castle, back home in Durham, reveal the sense of relief that was felt.

On May 5, 1945 – three days before VE Day – an officer of the 9th Battalion was quoted in the newsletter as saying: “The End for us!! At 0800 hours the unconditional surrender to Field Marshal Montgomery of all troops facing us was accepted. It was over then as we knew it must be. How did we feel – quiet, thankful – thankful too for a good night’s kip.”

At 13.30 hours on May 7, there was a formal announcement: “They’ve packed up,” it said. All German forces had surrendered unconditionally. It was effective from May 9, but no further offensive action would be taken.

The 9th Battalion had been expecting to advance into Denmark but, as Nazi defences folded, that latest leg of their war was not required. Instead, they celebrated VE Day on May 8 at Hademarschen, just south of the Kier Canal.

The unidentified 9th Battalion officer in the DLI newsletter takes up the account of the VE Day celebrations: “Verey lights, flares, Bofors and bonfires were the order of the day, whilst the Officers and Sergeants did themselves well, and everyone did what they could to mark the occasion. We were still operational, however, and that does tend to cramp one’s style in these affairs. This then was the end of the campaign for us.”

Steve Shannon, who worked with the DLI Collection for many years, recalls fascinating conversations and correspondence with Captain Roy Griffiths, who had served with D Company of the 9th Battalion from El Alamein through the invasion of Sicily, the D-Day landings and on to the end of the war.

His memories – anecdotes, letters and photograph albums – sent to Durham from his home in Surrey, 30 years ago, have enriched the archives at the Durham County Record Office.

“What he gave us was a really important contribution,” says Steve, who now works part-time for the county council in the Durham County Record Office. “He wanted to make sure his collection wasn’t lost after he’d gone and would be kept in a place where it would be properly looked after and appreciated. By giving it to the DLI archive, he was ensuring its survival.”

Captain Griffiths joined up as a sapper in the Royal Engineers before being commissioned into the DLI as an officer.

Among the photographs he entrusted to Durham is one of him leaning against a Bren gun, with a revolver strapped to his waist and wearing a fine pair of black leather, sheepskin-lined Luftwaffe boots he had 'liberated'.

“He’s also wearing a parachute scarf, so you would say he was casually dressed for war, but he was especially proud of those boots,” recalls Steve. “He was also very proud to be in the DLI and to be part of D Company.”

It remains a mystery how the boots were 'liberated', where they’d come from and who had originally owned them.

After VE Day, 9th Battalion were in a temporary base until they were ordered to go to Berlin, arriving by road from Hamburg on July 30, when they joined British, Russian, American and French forces occupying the devastated city.

The main task was to carry out curfew patrols and security guard duties, with roles including Potato Guard, which involved guarding stores of potatoes. But, with the fighting over, the men also had enough time to enjoy themselves, and Steve recalls Captain Griffiths saying what a good time they’d had in Berlin.

Another member of the 9th Battalion is on record in another DLI newsletter as saying: “We are in Berlin as this goes to press, and life here is quite unbelievably fantastic”.

The British Army laid on a range of entertainment including cinema, theatre, swimming, boating, tennis, hockey, riding and football, with the 1936 Olympic stadium commandeered for many of the sporting activities.

“Initially, they were strict about no fraternisation with the civilians,” says Steve. “The British Army was really scared about the health of the men, and there were all sorts of rules about not eating in cafes and restaurants in case they hadn’t been tested for disease, but the restrictions slowly eased.”

Another bulletin from the DLI newsletter at the time states: “The fraternisation ban has been lifted now and both parties seem very willing to fraternise, though home press accounts are somewhat exaggerated. A few men can be seen dancing at public dance halls, whilst there are a number of civilian cafes and restaurants, which, having been vetted from the medical point of view, are open to British soldiers."

However, despite the lighter atmosphere, the darker consequences of war were never far from the surface of city life. The newsletter reveals: “The Black Market exists, and one cannot be blind to it; fantastic sums change daily for the most ordinary goods, whilst the Berliner has already reached the stage of selling his soul for the chance of a square meal. Beneath a superficial atmosphere of gaiety lies the stark reality of starvation and disease. The destruction wreaked by incessant bombing and weeks of street fighting defies description.”

There had already been two victory parades in Berlin before the Durham soldiers arrived. Field Marshal Montgomery joined Marshal Zhukov, commander of the Soviet forces, to take the salute on July 12. Then Winston Churchill and Clement Atlee followed on July 21.

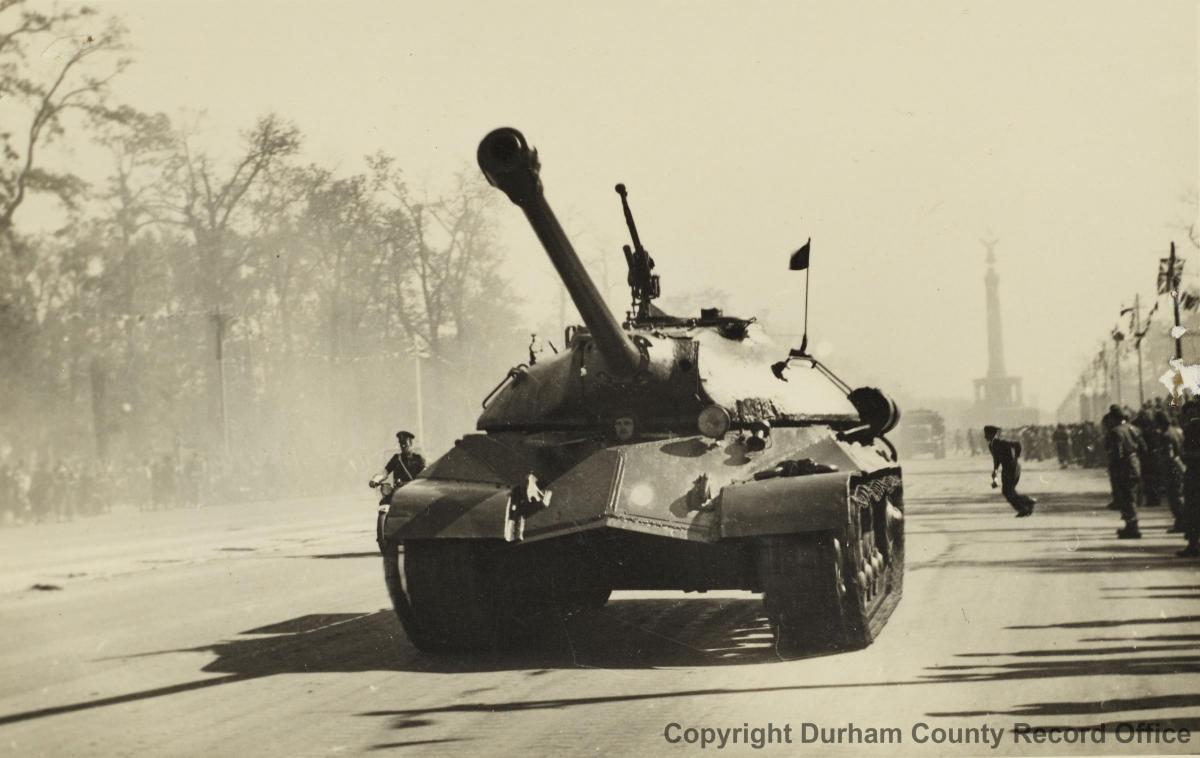

The 9th Battalion got their turn on September 7, when a parade of all the Allied forces in Berlin was held in Tiergarten to celebrate victory over Japan. The DLI’s colours were flown over specially from Brancepeth and were proudly raised as the Durham soldiers marched past General Patton, Marshal Zhukov and other Allied generals.

Photographs in the DLI archive include one of Captain Roy Griffiths taking part in the parade, although he was back in his regulation British Army boots by then.

The war was over, the Durham Light Infantry had played a distinguished part, the regimental flag had fluttered over the mass ruins of Berlin and the soldiers were finally released to begin their weary, but heroic, journey home to Blighty.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel