THE war was over. Victory was proclaimed. Bells, free from muffles, rang from every church steeple. Tables, chairs and pianos were tossed out into the street for impromptu parties; town centres filled up with joyous youth making "whoopee" – to use an Americanism which had come over here during the war.

And, as night drew in, everyone gasped as public buildings which had been blacked out in darkness for five-and-a-half years were suddenly floodlit once again.

People had been waiting for victory to be declared for some weeks, but late on May 7, 1945, it became known that the Germans had unconditionally surrendered and that May 8 would be an official national holiday – "Today is V-Day", shouted The Northern Echo's front page headline.

"In Hartlepool, the noisiest period of the day was at the very beginning when, at midnight, ships in the harbour rent the air with the victory sign on their sirens, combined with bursts from machine guns, which sent tracer bullets in a red stream into the sky," reported the Echo.

But as the end of the war had been so long in coming, the rest of the North-East dared not believe it had really arrived without official confirmation. So no one really knew whether they should go to work and put their backs into the war effort or whether they should stay at home and celebrate.

"At 11am, Stockton High Street was a mass of people walking aimlessly about or draped over the pavement barriers waiting for something to turn up, " said the Darlington and Stockton Times (D&ST).

"The impression one had was that the suddenness of the announcement – it had been expected the previous day – came almost as an anti-climax and that with all that the people had endured, and in hundreds of cases suffered, there was little disposition to throw aside all restraint."

Then it rained at lunchtime. "Redcar, Saltburn and Marske were gaily decorated but continuous rain drove jubilant people indoors," said the Echo.

Red, white and blue bunting was the order of the day because people were able to purchase it without using up precious rationing coupons. Similarly, the Government allowed black-out restrictions to come to an end and celebratory bonfires to be prepared, as long as there was no material with salvage value burned.

The rain cleared up just in time for 3pm when Prime Minister Winston Churchill took to the airwaves, from the same room in the War Cabinet Office that his predecessor Neville Chamberlain had used on September 3, 1939, to broadcast that war had been declared, that the conflict was officially over.

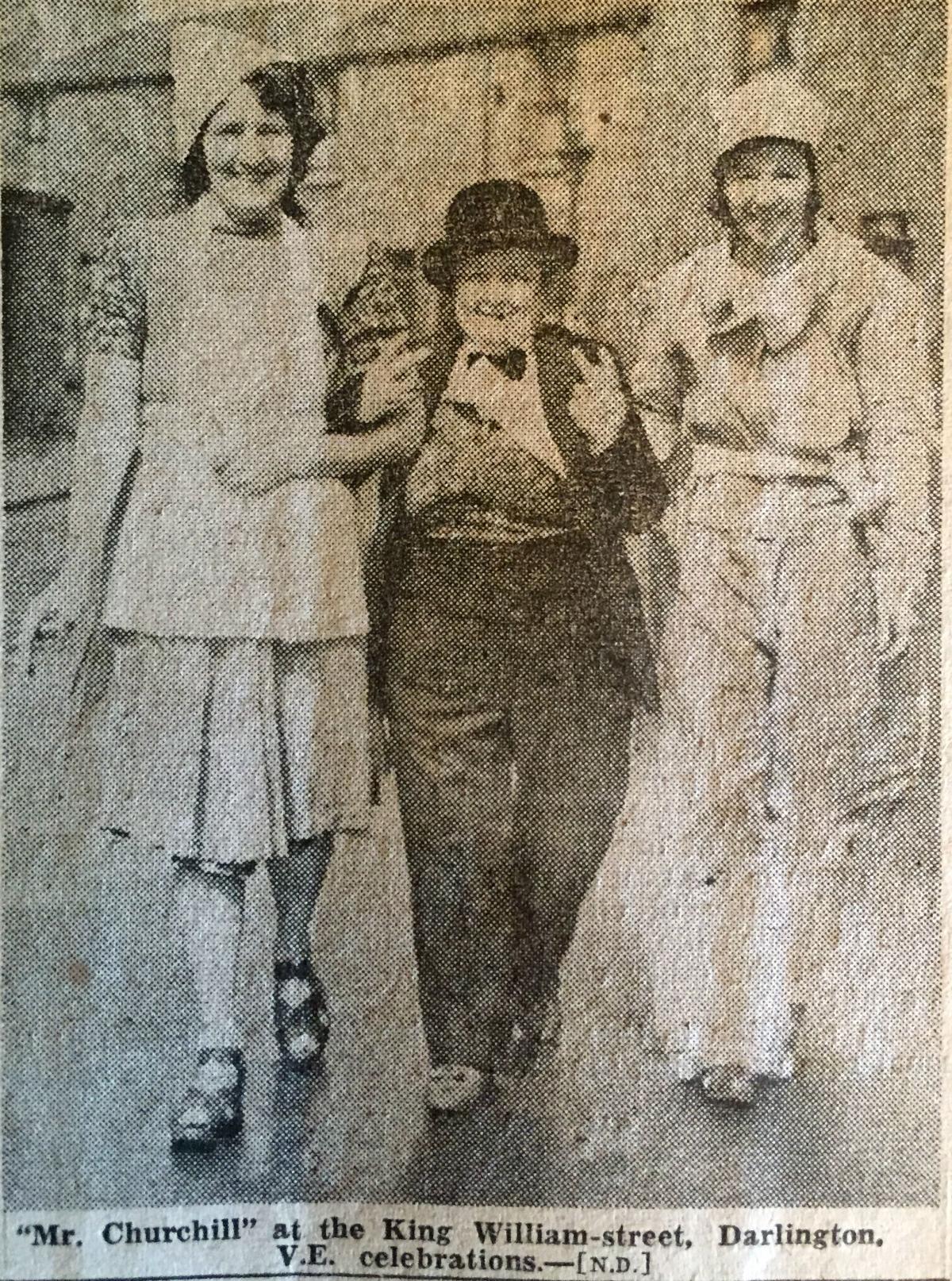

Churchill was the national hero – in so many of the pictures published in The Northern Echo and its sister evening paper, the Evening Despatch – people are show attending parties dressed as him, with his trademark cigar and back-to-front V salute. When he made an impromptu appearance on the Ministry of Health department balcony in London that afternoon, he told the crowd: “This is your victory.” But the crowd shouted back: “No – it's yours!”.

During his wireless broadcast, he soberly said: “We may allow ourselves a brief period of rejoicing; but let us not forget for a moment the toil and efforts that lie ahead.”

This really fired the starting gun for the day's celebrations as the North-East threw itself with gusto into that brief period.

"Shortly after Churchill's speech, a ship off Sunderland fired 20mm Orkilon shells in celebration towards the Fulwell district, " said the Echo. "Mrs R Lord of Osborne Street was listening to the wireless when a shell went through the roof and became embedded in the ceiling of the kitchen, but fortunately did not explode. It was removed by a neighbour."

Elsewhere, the noise was not quite as explosive, but certainly cacophonous. In Sedgefield, immediately after the Prime Minister’s speech, the bells of St Edmund’s Church rang out a victory peal.

"At Middleham in Wensleydale on Williams Hill," reported the D&ST, "from the old Roman fort, the bells of five churches were heard simultaneously, viz Middleham, East Witton, Wensley, Leyburn and Spennithorne."

Streets spilled out into their spontaneous parties. In Catterick, the RAF organised dances and cinema shows for adults and treated 200 children to tea. In Winston, there were children's sports in farmer's field; in Great Aycliffe there was a baby show and ankle competition on the green.

"In Seaham Harbour, ships in port were gay with bunting and flags flew from the pulley wheels at Seaham, Dawdon and Vane Tempest collieries," reported the Echo, the miners' bible.

In many towns, people were searching the centres for some civic announcement, or some symbol, to make sense of it all. In Richmond, someone found a Union flag which had been forgotten since 1910 when children of Richmond, Tasmania, had sent it to their North Yorkshire namesakes. The flag was proudly flown from the top of Trinity Tower in the Market Place.

"In Middlesbrough, the mayor (Councillor R Ridley Kitching) made a brief address from the town hall balcony,” said the Echo. "He appealed to the people to take their share in the building of a better Middlesbrough, a better England, and a better world. The townspeople stood in reverence for one minute to those who had made the supreme sacrifice."

Stockton – again – was similarly restrained. "The mayor (Coun A Ross) had a son in the Far East, " reported the D&ST. "He asked everybody to go back to work after the holidays and to work as hard as ever to assist the war against Japan.

"We had, he said, got over the first hurdle and we must work religiously until we had surmounted the second."

This was the dichotomy of VE Day. While some people celebrated as if their lives depended upon it, other people were mourning the lost lives of loved ones. On VE Day, the Echo reported the announcement of the death of George W Sains, 18, of Signal Company, US Third Army, who was the grandson of Mrs M Sains, of 5 Oxford Street, Eldon Lane.

There was also tragedy amid the celebrations. In Whitby, a soldier drowned while celebrating his escape from hostilities, and back at Winston, on the edge of Teesdale, an Army lorry overturned on its way in to Darlington, hospitalising three soldiers and killing Sgt-Maj Newall-Smith, a female member of the ATS.

The Echo reported that York "was strangely quiet, in striking contrast to the hilarity of Monday night, when Canadian and French airmen joined with English servicemen and women and their friends in making considerable 'whoopee'."

Durham City was also "quiet". "The undergraduates, with a preponderance of women, marched into the Market Square in the forenoon and danced round the policeman seated in the traffic control kiosk."

As the evening wore on, though, the beer took its effect and the bonfires burned. A farmer used his tractor to carry a load of material up Roseberry Topping, while in Richmond, the High Moor beacon was set alight at 10.45pm.

“In doing so, the Mayor said that in days gone by the beacon was lighted in case of danger from enemy invasion, but today it was lit to express their joy and thankfulness for the victory of their gallant forces,” said the D&S.

Richmond, of course, was an Army town – headquarters of the Green Howards and the watering hole of the thousands of soldiers at Catterick camp. Little wonder the scenes here were as joyous as anywhere.

“For the first time in history, dancing took place in Queens Road,” continued the D&S, “the road being effectively illuminated by electric lamps suspended from the trees. Dance music from records supplied by Mr Murphy, amusement caterer, was amplified and dancing continued until 1am when the National Anthem was sung.”

Many smaller places also threw themselves into elaborate celebrations. "Effigies of Hitler, hanging by the neck with his paintpot and brush, were a feature of Fishburn V-day celebrations," said the Echo of the village's three bonfires.

"Another topical tableau was that of a model coalmine decorated with coloured lights with the slogan 'Fishburn has done its bit' in recognition of the local colliery having an output which is always on the target."

Hitler, poor fellow, had a rough night, being burnt in many different places. In Hutton Rudby, Sir Bedford Dorman, son of the Middlesbrough ironfounder, ignited a huge bonfire which had sprung up on the village green with the German fuhrer on top.

Barnard Castle's celebrations "culminated at about midnight when a stagecoach in which Hitler lolled by the window was trundled into the market place and set on fire. There was a terrific blaze, and the figure inside went off with a bang. It was a satisfactory finale."

Darlington seems to have seen the region's most boisterous celebrations. At one point, there were 1,200 inside St Cuthbert’s Church for a thanksgiving service, and thousands more outside in the Market Place and thronging High Row.

They climbed poles, ripped down flags, sang popular songs with the lyrics changed and used two Belisha beacons which were used in a football-cum-rugby match "that made Sedgefield's Shrovetide game tame by comparison".

The council had erected a platform and a PA system in the hope of holding some organised dancing but “good-natured rowdyism negative the well planned devices”. Men from the Royal Welsh Guards took control of the platform, and sung songs with “a rare gusto”.

“All the time, a frequent explosion of detonators caused sundry alarms among the crowd, some of whom sought safety on the top of air raid shelters outside Central Hall,” said the D&S. “Here a number of soldiers indulged in a burlesque of classical dancing to the amusement of the crowd, but a sudden detonation ended the exhibition, as well as causing an immediate diminution in the shelter roof congregation, which had grown to alarming proportions.”

Darlington Memorial Hospital was nearly full with casualties. “They were lying all over the floor, but none was detained,” said a nurse. “There were such cases as a hit on the head with a bottle, a girl who collided with a soldier and people who had been struck with something, but there was nothing serious.”

London, of course, was the epicentre of national celebrations, and tens of thousands of people were outside Buckingham Palace, where the King George VI and Queen Elizabeth made eight balcony appearances to rapturous receptions, and many, many more filled Trafalgar Square and its fountains.

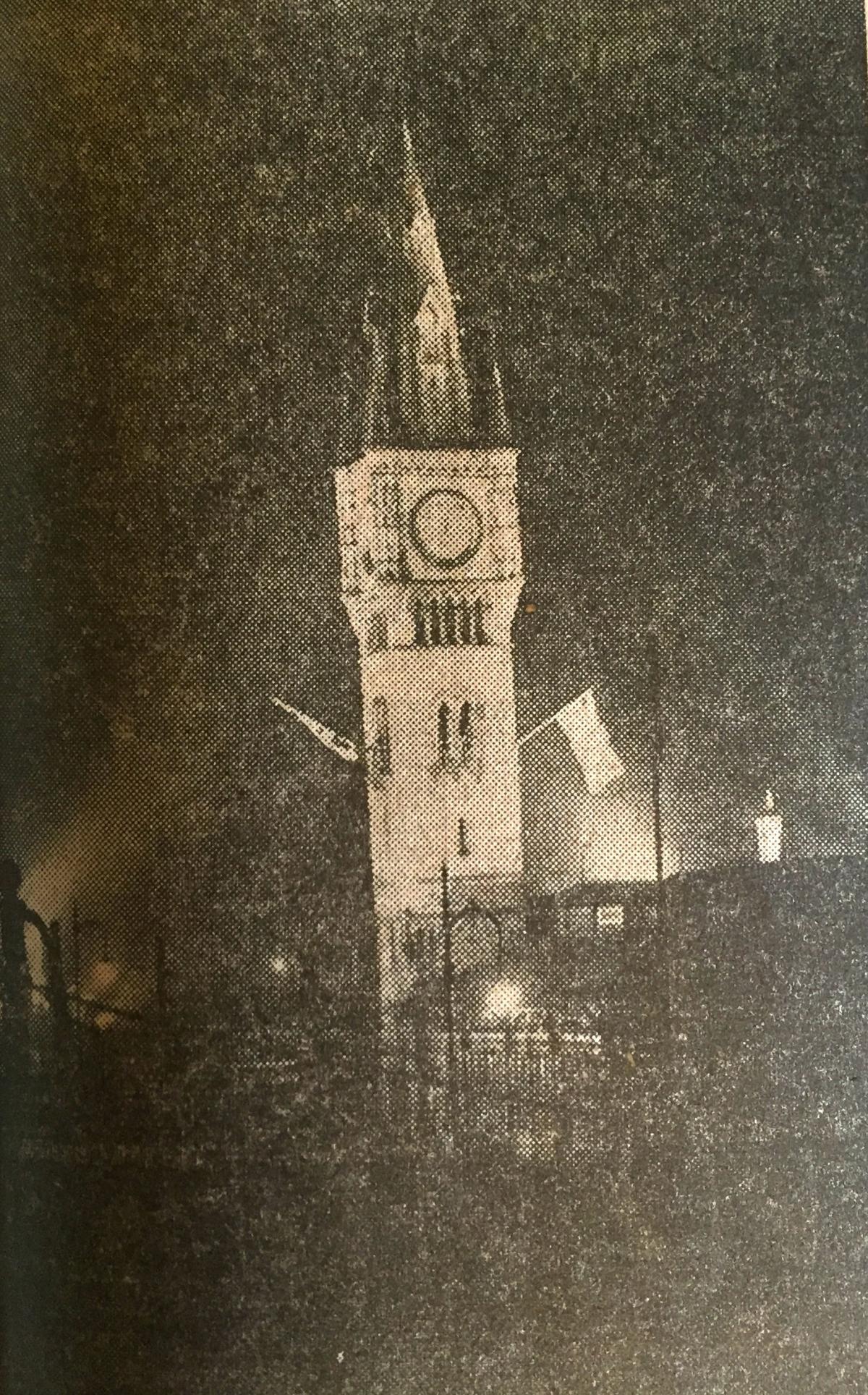

A symbolic moment was when St Paul’s Cathedral, that great and extraordinary survivor of the Blitz, was floodlit and two searchlights made a V in the dark sky above it. A similar effect was tried in Darlington.

“The floodlighting of the Town Hall clock tower and St Cuthbert’s Church held the attention of the crowd which, however, did not disperse until after midnight, whiling away the time by informal community singing,” said the D&S. “In this direction, a large circle of revellers were particularly successful, their extensive repertoire ending on a triumphant note with Land of Hope and Glory.”

However, probably to the authorities’ relief, celebrations came to a natural end. The Echo’s Stockton reporter wrote: "Those who sought their homes after midnight had their way illuminated by an amazing display of sheet lightning while thunder roared in the distance recalling to the more imaginative the flashes of the worst nights of the air raids."

But, after more than five-and-a-half years, there were no more air raids. The threat had lifted, the war was won and the skies were clear of planes. The thunderstorm was just the good old British weather’s way of beginning the return of life to normal – with an early summer soaking.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel