CORONAVIRUS will not be beaten until we have a vaccination against it – but even then there may be some dangers, as the death of young Jonathan Staley in Teesdale in 1774 shows.

His cause of death was “inoculation”.

Smallpox, as those who have been following our surprisingly popular “plague of the week” feature will know, regularly ravaged the country in previous centuries.

Christine Jemmeson has transcribed the parish registers of Middleton-in-Teesdale and even among the scattered population of England’s least inhabited district, there were still occasional outbreaks.

In 1768 in Upper Teesdale, there were three deaths from smallpox with three more recorded in 1774.

Christine’s ancestors, Thomas and Margaret Staley, obviously and understandably wanted to protect their children from the disease, even though they lived at Underhurth near Langdon Beck which is about as far flung as you can fling.

So young Jonathan was inoculated.

This involved a doctor introducing material from a fresh pustule on a sufferer into a scratch on a healthy person’s arm or leg, infecting the healthy person – but hopefully only mildly. Nevertheless, there was still a significant localised infection which encouraged the body to produce antibodies which gave the person immunity against any future attacks – should, of course, they survive the inoculation.

The Chinese had developed the concept of inoculation around the 10th Century, and it was popularised in Britain by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, whose beautiful face bore the deep scars of her brush with smallpox. Her husband was the British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire based in Istanbul where Lady Mary noticed the Turkish enthusiasm for inoculation. Desperate to prevent her children suffering her fate – or worse, like her brother, who had died aged 20 of smallpox in 1717 – she had her five-year-old son inoculated in 1718.

He survived, the family returned to London, where in 1721 Lady Mary had her four-year-old daughter inoculated in the presence of royal doctors.

She too survived. When prisoners, who volunteered for a trial inoculation in return for their freedom, also survived, the royal doctors began inoculating the daughters of the Prince of Wales.

And so inoculation spread – even to the leadminers in a distant dale.

But it had dangers. About three per cent of those inoculated either died of smallpox or of an infection like tuberculosis or syphilis that was introduced to them at the same time.

The unfortunate Jonathan was one of those three per cent.

It wasn’t until Edward Jenner in 1796 came up with a vaccine that inoculation became a safer procedure. Jenner was a remarkable fellow. He made hot air balloons and came up with a theory about young cuckoos throwing their hosts’ chicks out of their nests – such a ridiculous theory that it was widely ridiculed until photographic evidence in 1921 provided Jenner correct.

He also wondered why dairymaids believed they were immune from smallpox if they had contracted the milder cowpox from their herds. He tried inoculating healthy people with cowpox, triggering a slight reaction, and then injecting them with smallpox. When they showed no signs of falling ill, he had proved that his cowpox vaccination (vacca is Latin for cow) had worked.

Because it is counter-intuitive, it was still controversial, and conspiracy theorists used Jenner’s nonsensical ideas about cuckoos to rubbish his vaccination theory.

In 1856, vaccination was made compulsory in England within seven months of birth, or parents would be fined £2 which could lead to imprisonment. In 1867, a second law insisting on a second vaccination after puberty was passed.

At this time, Dr Richard Taylor Manson appeared in the Durham dales. He was a Liverpudlian who’d come to Heighington to run a boarding school before qualifying in medicine at Newcastle university. He set up a surgery in Witton-le-Wear and lived in Bridge Field House in Howden-le-Wear, and he was a confirmed believer in the efficacy of vaccinations.

He always said that his first patient was George Sisman, as he was present at his birth, in Witton-le-Wear, on January 17, 1868. Dr Manson was so convinced in the value of vaccinations that he vaccinated baby George on three separate occasions.

George was not so convinced, and he grew up to become secretary of the Darlington Anti-Vaccination Society, one of the most virulent local groups in the country at the end of the 19th Century. They believed forced vaccination by the state to be an infringement of their civil liberties, and they worried about the world’s over-reliance on technology, and they paid the fines of those who didn’t have their children vaccinated.

Perhaps the virulence of the Darlington anti-vaccinationists was a reaction to Dr Manson’s enthusiasm. Having vaccinated most of Weardale, and perhaps even Jonathan Staley’s descendants over in Teesdale, he became Darlington’s Public Vaccinator, and turned his needles on the town’s youngsters.

While George’s society faded from view, Dr Manson became one of Darlington’s most upright citizens. A councillor for 20 years, he thrice turned down the opportunity of becoming mayor.

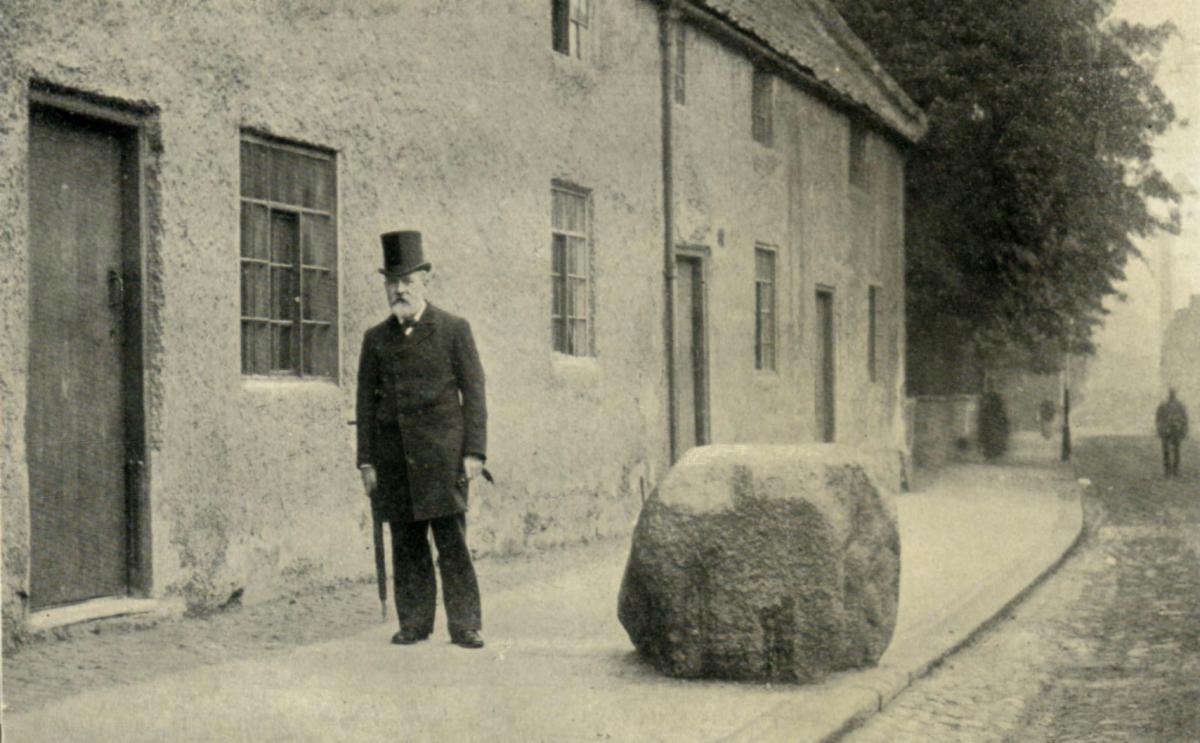

His big love was nature and particularly geology. He founded the Darlington and Teesdale Field Naturalists’ Club, he wrote nature columns for The Northern Echo, and when he died in 1900, one of his favourite rocks was dredged out of the Tees at Winston and placed in South Park as a memorial to him. There is still a plaque on it, noting his scientific and literary work.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel