IMMEDIATELY after Richmond MP Rishi Sunak's maiden Budget, Stockton South MP Matthew Vickers gave his maiden speech to the House of Commons. These speeches are usually gentle, introductory affairs in which the new MP tells the House a little about the place they have come to represent.

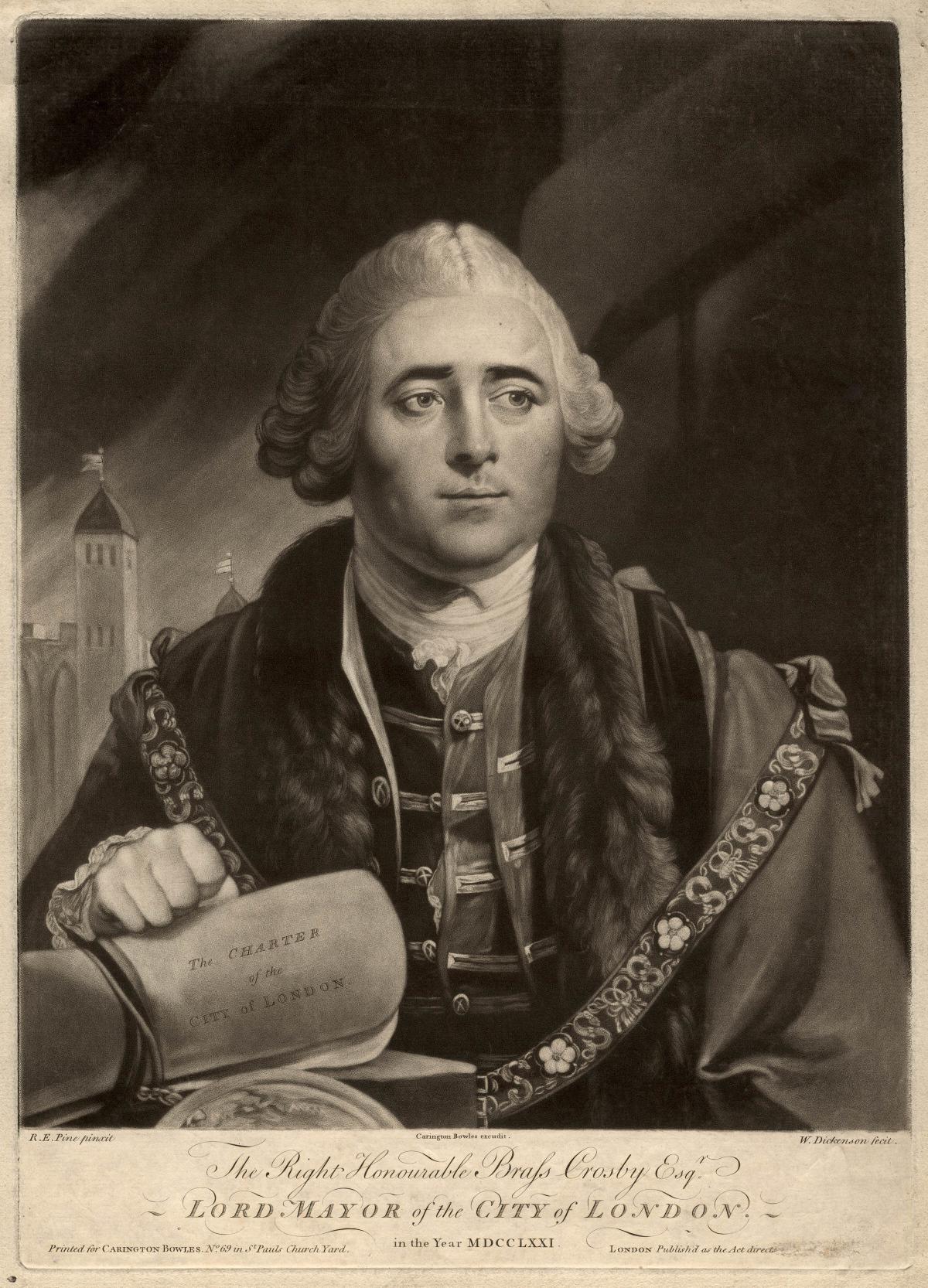

Hansard records that Mr Vickers said: “Stockton has a knack of producing the finest inventions, and some of the finest minds. Brass Crosby, the stoical politician and former Lord Mayor of London, stood passionately for what he believed in, and was committed to the Tower of London for trying to install transparency in this place. This fellow Stocktonian was a titan of his time…”

Indeed he was. In fact, the only reason we are able to report precisely what Mr Vickers said in the House is because of Brass Crosby.

He was born in Stockton on May 8, 1725. His father was Hercules Crosby and his mother was Mary Brass, hence his distinctive first name. Mary was the co-heiress of the Brass family of coalowners of Blackhall on the Durham coast.

He was educated at The Hermitage overlooking Norton village green, and he became apprenticed to a Sunderland lawyer before heading to London to seek fame and fortune – some people have called him Stockton’s Dick Whittington.

His great good fortune was the three rich widows whom he married. They gave him provided him with the finance to get a start in politics in the days when you could buy, or bribe your way into, official jobs.

In 1768, he was elected MP for Honiton in Devon - a corrupt "potwalloper" seat (only people with a hearth large enough to boil a pot, or wallop, could vote). Two years later, he was elected Lord Mayor of London, which meant he was also the capital’s Chief Magistrate.

When he took up the position, he swore to the people of London that "at the risk of his life he would protect them in their just rights and privileges”.

This brought him into conflict with the king, George III, who was recruiting sailors to fight the Spanish over the Falkland Islands. Pressgangs toured the streets, seizing likely recruits – Crosby, as Chief Magistrate, prevented them from operating within the city.

But the big conflict came in 1771. These days, MPs will do anything to get themselves in the papers or on the telly or splashed across social media; back then, newspapers were not allowed to report what was said in the House in case an MP said something that made him look silly.

So newspapers fictionalised their Parliamentary accounts. They gave them ironic titles, like the Proceedings of the Lower Room of the Robin Hood Society, with the speakers being given mocking, but anonymous, names. Sir Robert Walpole, for example, was referred to as "Sr. R―t W―le”.

In February 1771, John Miller, printer of the London Evening Post, decided to fill in the blanks and print verbatim what MPs had said. The Earl of Onslow, the MP for Surrey, objected, and the Serjeant-at-Arms sent a messenger to capture the culprit.

Miller was arrested and brought before the magistrates, chaired by Crosby. The Parliamentary authorities expected Miller to be imprisoned for such a terrible crime, but Crosby refused. Instead, he had the messenger jailed for assault and false imprisonment.

Crosby claimed he was following his oath to protect the rights of Londoners.

The Parliamentary authorities were outraged. They demanded Brass attend the House to explain.

But the poor fellow was stricken by a bad bout of gout, and a huge crowd of his supporters had to carry him into the Commons.

The authorities realised that he was becoming a cause celebre and said he was too ill to face them. Crosby, who liked a good scene, proclaimed that he was guilty of disobeying Parliament by releasing the printer and demanded that he be punished by being sent to the Tower.

George III, who had previous with Crosby, felt he had no option but to punish the Lord Mayor, although he had Brass rowed up the Thames to the Tower in a boat so his land-based supporters couldn't free him.

For two months the hero from Stockton languished in the jail.

When Parliament was dissolved on May 8 – Crosby’s 46th birthday – he was released. A 21-gun salute greeted him. Huge crowds cheered him. A triumphal procession carried him through the streets, grateful people pulling his carriage instead of horses. At night, the city was illuminated in his honour.

Never again has Parliament tried to suppress reports of its debates, with Thomas Hansard becoming Parliament’s first official printer to record what was so said.

Hansard records that Mr Vickers finished by saying: “While I don’t plan on spending a night in the tower, I’ll be as ‘bold as brass’ in standing up for Stockton.”

Because it is said that the way Crosby bravely stood up to the MPs, the House authorities and the king is the derivation of that phrase – he was as bold as Brass.

He died in 1793 and is buried in Chelsfield, Kent, where through his third wife he’d become Lord of the Manor. There’s a memorial to him in the nearby church; there’s a blue plaque to him in Bromley, where he lived; there’s a street named after him in Southwark; there’s an obelisk in his honour in the centre of St George’s Circus in London, and in Canada there are two townships – North and South Crosby – which bear his name (although in 1998, they merged into a town named after a Devon family of settlers called Bastard).

Stockton has nowt. Anyone know an MP who might be prepared to get him memorialised in his hometown?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here