WALTZING MATILDA, Australia’s unofficial national anthem with its lyrics about a jolly swagman camping by a billabong in the shade of a coolibah tree, was written by a railwayman from Shildon.

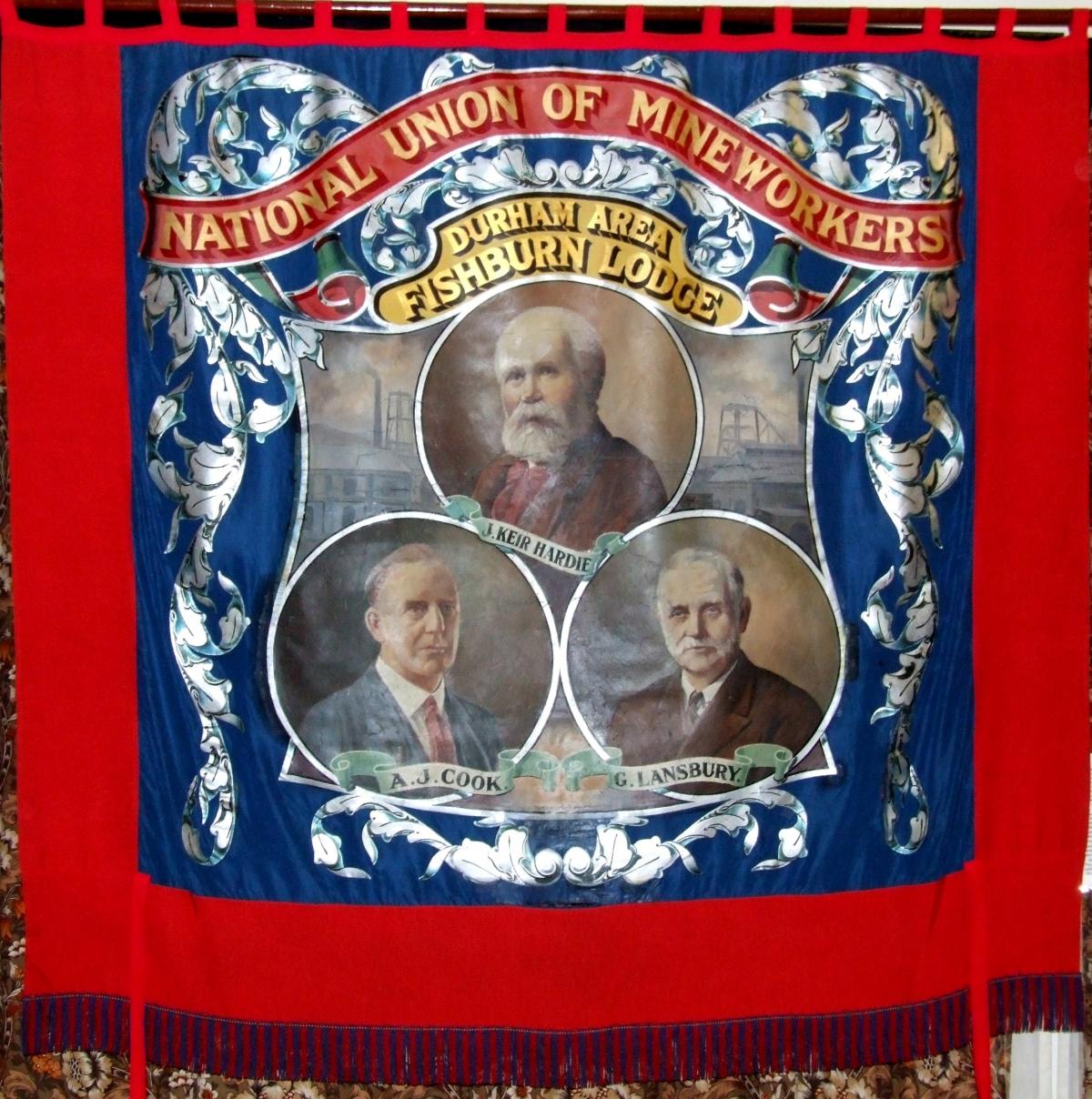

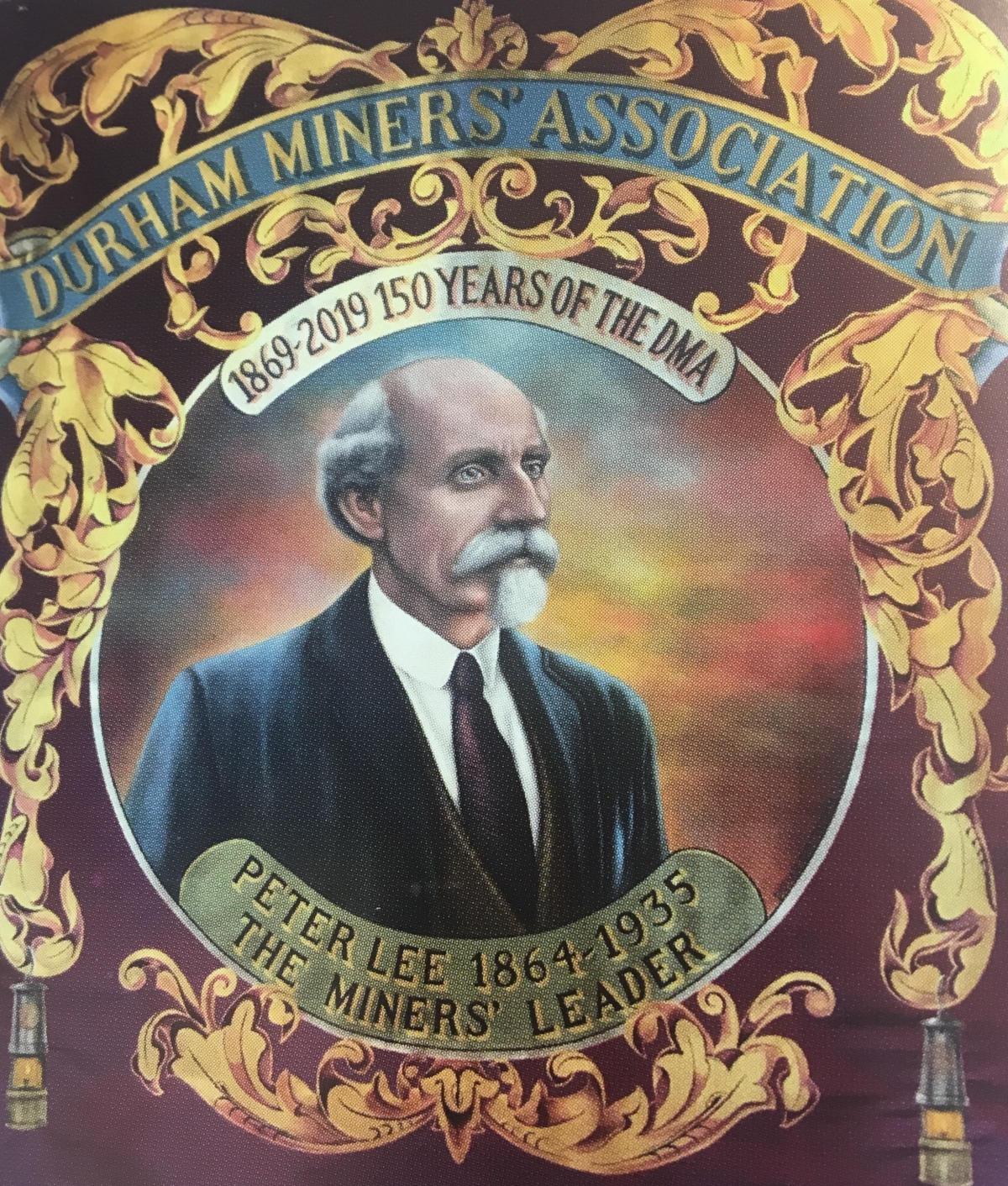

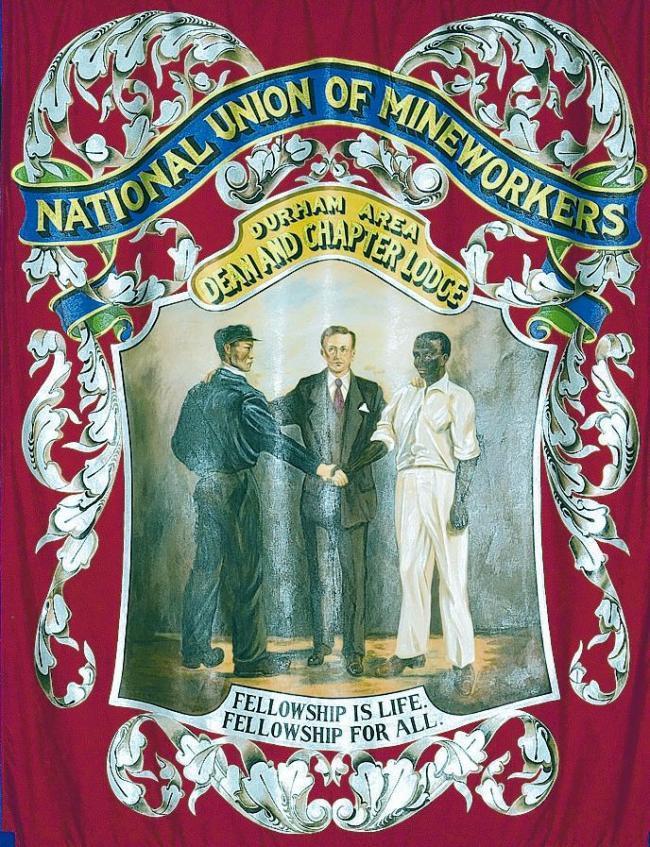

The works of Thomas Bulch are to be heard again in his hometown on April 25 in a special concert at the Locomotion museum, where they will be played by one of the world’s best brass bands surrounded by banners from the Durham coalfield.

The Banners and Brass concert will also include compositions by a second Shildon railwayman, George Allan, who was born just 15 months after Thomas. Together, the two men were responsible for more than 430 known compositions and arrangements which were – and still are – played by brass bands around the world.

The brass band era began in the 1840s and 1850s with the growth of working class, industrial communities, and was aided by technological advances that enabled the mass production of reliable instruments. The brass band, like the banner, became an expression of identity, and competition between communities was friendly but keen.

In 1857, railway telegrapher Francis Dinsdale formed the New Shildon Saxhorn Band – the town’s first proper band.

Saxhorns were a family of seven instruments, designed for bands by Adolphe Sax, who patented them in Parish in 1845. They were, then, extremely fashionable when Francis struck up his band, even if in July 1858 its performance at a horticultural fete in Darlington was described as “chaotic”.

The Wear Royal Yacht Club Band, from Sunderland, came third that day, and Francis recruited its conductor, Robert de Lacy, to bring order to Shildon. It worked, as in 1860 Shildon were good enough to compete in the Great National Contest at Crystal Palace, and de Lacy went on to be the vicar choral at St Paul’s Cathedral.

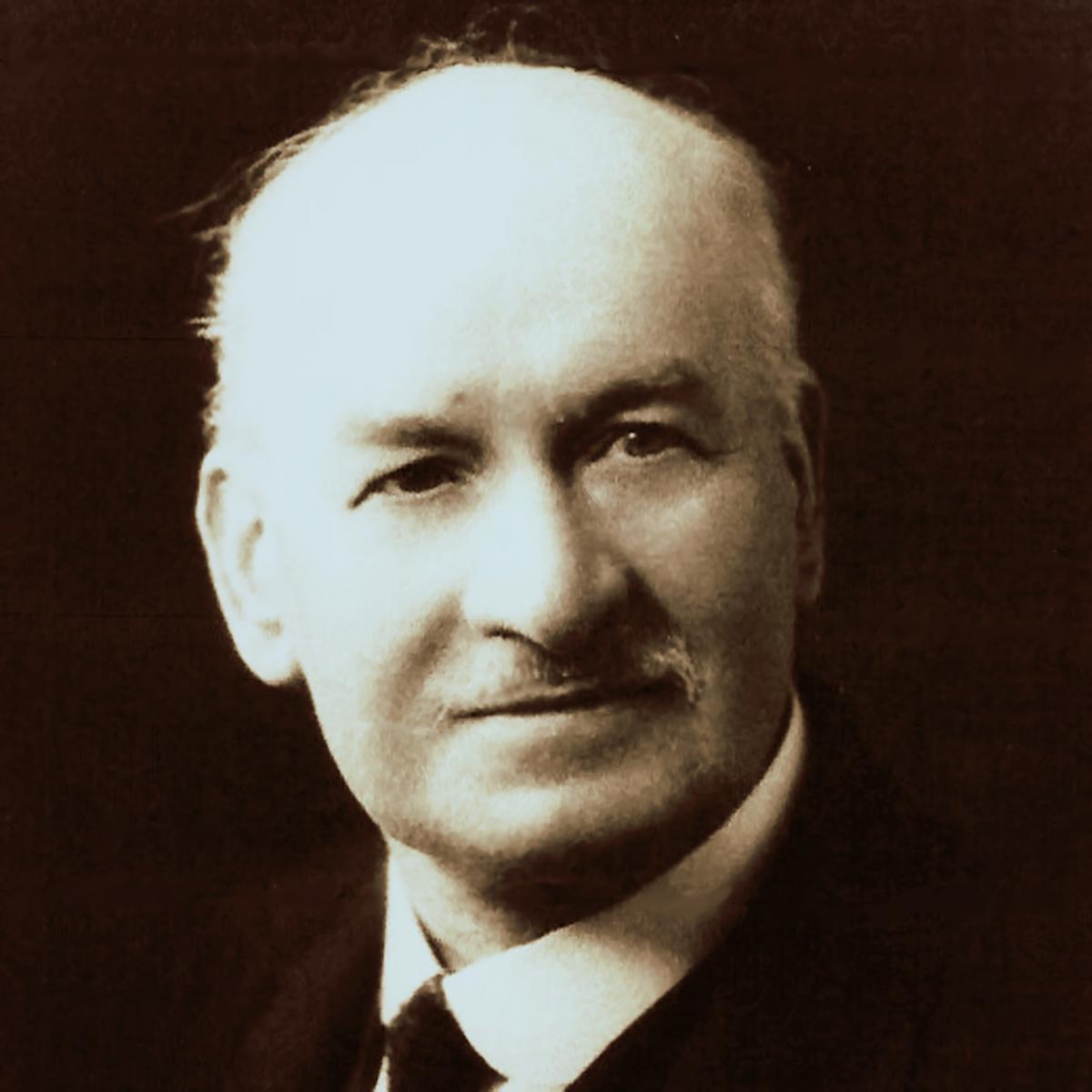

Francis passed on his passion for music to his children and then to his grandchildren, particularly his daughter’s lad Thomas Bulch, who was born in New Shildon in December 1862. Thomas was taught the cornet, piano and violin and proved himself to be a good whistler.

Growing up in Adelaide Street, Thomas attended the British School and joined the Saxhorn Juvenile Band which was led by his uncle, Edward, and then became an apprentice blacksmith in the wagonworks.

Following a similar musical path was George Allan, the son of a North Yorkshire tailor who’d established a business in the new railway town. George was born in March 1864 and graduated from school to become a blacksmith’s striker, wielding a heavy hammer, at the wagonworks.

But rift developed in the Shildon banding community. In 1878, aged 16, Thomas left his uncle’s band and formed the New Shildon Temperance Band. Quickly he became bandmaster, and when he was only 17, the band was entering competitions playing his first march, The Typhoon.

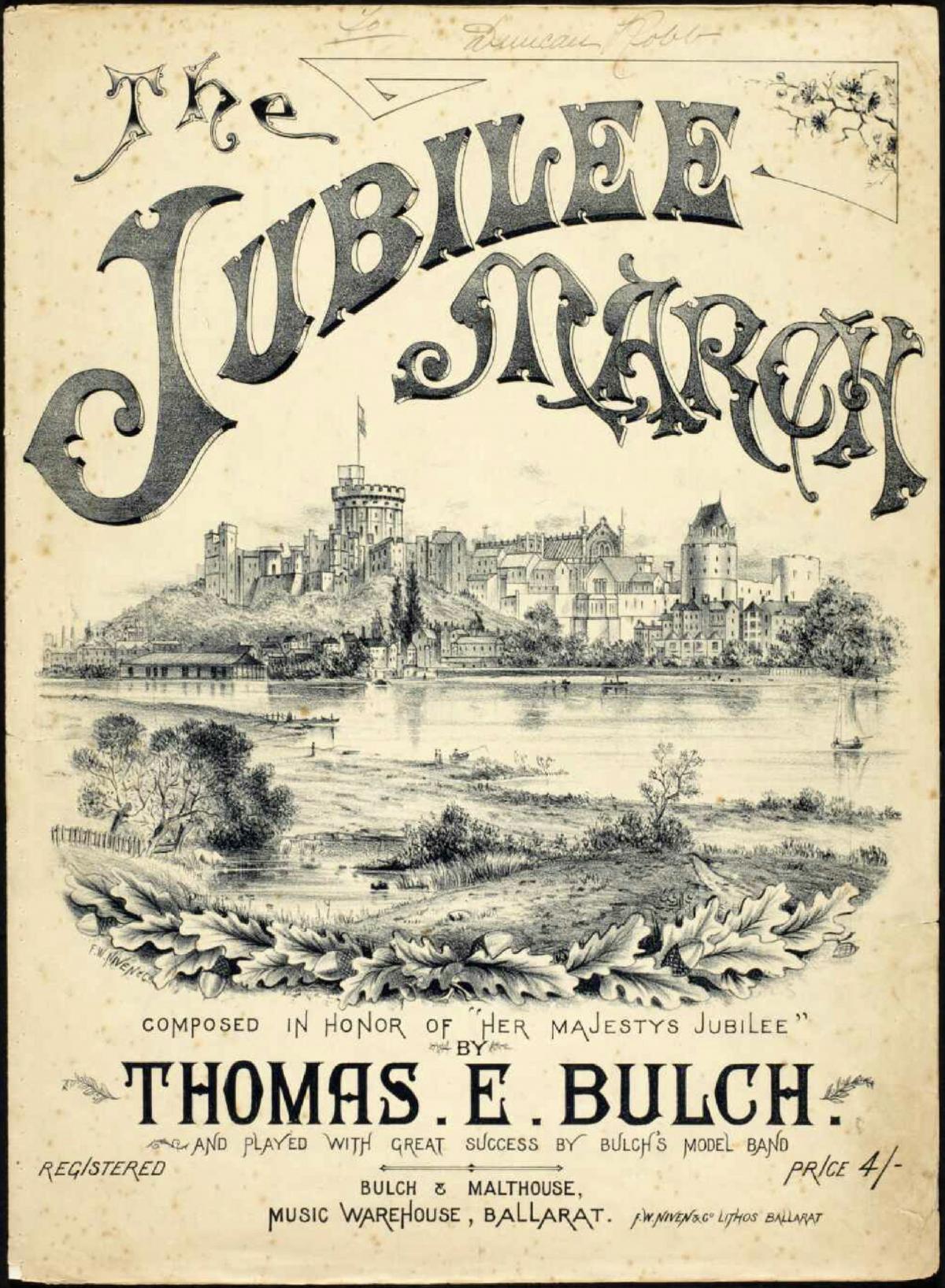

In those days, before the advent of recording, the equivalent to having a hit single was to have your sheet music published. The Typhoon was picked up by a publisher in Hull, giving Thomas his first chart success.

Under his baton, the Temperance Band was competing regionally, playing more of his compositions, and there must have been a sweet note of success when his band came second at the Shildon Show in August 1882, ahead of his grandfather’s Saxhorn Band – which included George – which came fifth.

But Thomas’ head was being turned. One of his bandmates, John Malthouse, had emigrated to work in the Australian coalfields and was writing to him about the joys of life down under, where the music scene was just beginning.

On March 22, 1884, up to 3,000 people gathered at Shildon station to see Thomas and three other bandsmen depart for the New World. It was particularly brave for Thomas – in 1855, his great-uncle had died when the ship he was emigrating on had run aground at Port Adelaide in Australia.

He was sailing on the West Hartlepool-built steamship Gulf of Venice, which left London and took two months to reach Adelaide, the bandsmen entertaining other passengers.

Thomas then travelled 350 miles to Creswick, a goldmining town in Victoria, where he took control of the Allendale & Kingston Brass Band and began organising Victoria’s first brass band contest.

He married the daughter of a goldmine and moved a few miles south to Ballarat, a classic goldrush town which now has a population the same size as Darlington. He established the Bulch & Malthouse Music Warehouse, selling instruments and the sheet music of his own compositions, offering lessons, running contests and publishing his own brass band magazine.

He was doing well enough in 1886 for his brother, Frank, to leave Shildon and join him. Thomas got him work in a goldmine where, tragically, he was soon killed in a landslip.

Frank would have brought news from home, where grandfather Francis had recently died and young George Allan, still in the blacksmith’s shop, had succeeded as the saxhorn bandmaster. In 1887, George got married and had his first composition, a march called The Cyclone, published nationally.

Indeed, George had several tunes published, but he wasn’t as prolific as Thomas, who was producing so many pieces that he was publishing them under pseudonyms for fear that people would get fed up of hearing yet another Bulch composition.

In 1894, Thomas published in his magazine the music for a number called Craigelee by someone called Godfrey Parker – almost certainly one of his pseudonyms. Craigelee might have been his arrangement of a traditional Scottish piece, Thou Bonnie Woods o’Craigelea, or it might have been named for his wife’s grandmother, who was out in Australia and whose maiden name was Craigie – Thomas named several of his compositions after female family members.

In April 1894, a band played Craigelee constantly during the three-day race meeting at Warrnambool, a coastal town about 100 miles from Ballarat – perhaps Thomas himself was in the band. The irritatingly catchy melody lodged in the brain of racegoer Christina MacPherson, and she sang it all the way home to her family’s cattle ranch in Queensland.

One of her brother’s had a guest at the ranch, bush poet Andrew “Banjo” Paterson, who heard her picking out the melody line on a zither. He was working on a folk poem about an itinerant worker – a “swagman” – who was walking from place to place – or “waltzing” – with his possessions tied up in a piece of cloth and hung over his shoulder – a “matilda”. The itinerant was resting by an oxbow lake – a “billabong” – in the shade of a type of eucalyptus tree which grows in marshy conditions – a “coolibah tree”, while he was boiling some water in a billy can…

His words seemed to fit the melody line borrowed from the Shildon composer:

Once a jolly swagman camped by a billabong

Under the shade of a coolibah tree,

He sang as he watched and waited 'til his billy boiled

You'll come a-Waltzing Matilda, with me

The song, which has political undertones about the violent Great Shearers’ Strike of 1891, was first performed in April 1895 at a banquet for the Premier of Queensland, and Thomas never received any credit for it.

In fact, Thomas was struggling. The music warehouse burned down so he moved to Sydney where he was declared insolvent in 1897. Although still writing and still running bands, he took a job as a pianist accompanying the fast moving silent movies in the Geelong Mechanics Institute.

In Shildon, George was also finding musical life hard. His day job was still in the railway works, but industrial unrest made it hard to keep a band united – in 1911, in the depths of a strike, the army was called in to safeguard Shildon station.

He was, though, established as a good judge in banding contests across the north, and he was writing what is considered to be the best music of his life: he published The Wizard in 1909 and the majestic Knight Templar in 1912 – both were marches designed to highlight the skill of the band.

The First World War initially brought Thomas, with his Germanic sounding name, difficulties, and one of his sons died fighting in the trenches of France. But his patriotic compositions, Boys of Anzac and Heroes of Gallipoli, captured the public sentiment of the moment.

George retired to Leeholme in 1925, and his last public engagement was judging the brass band competition at the 100th anniversary of the Stockton & Darlington Railway celebrations in Darlington – he awarded first prize to Cockerton.

He died in 1930 and was buried in Shildon eight months before Thomas passed away in Sydney on the other side of the world.

They’d grown up together in the railway town, and although they spent most of the lives on opposite sides of the globe, they left an extraordinary repertoire of music which still inspires bandsmen the world over.

With thanks to Dave Reynolds, the Shildon councillor, whose website wizardandtyphoon.org is an amazing and detailed collection of information, and music, relating to Bulch and Allan.

BANNERS AND BRASS

7.30pm, Saturday, April 25, Locomotion, Shildon

The 35-piece NASUWT Riverside Band, ranked the 22nd best brass band in the world, will perform a special coalfield programme, including the works of Thomas Bulch and George Allan. The band’s backdrop will be mining banners and steam locomotives. Tickets are just £5 and can be booked by calling 01904-685780 between 10.30am and 3.30pm. Be quick – they are hot cakes.

The concert is the centrepiece of an exhibition of Durham banners which runs from April 20 to May 4. Entrance to the museum is free.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel