NORTH Durham was in uproar 150 years ago.

Thousands of people were on the streets because the Countess had come to town, trying to claim what was rightfully hers but which had been lost to her family for more than 150 years.

Armed only with an extremely large sword and a collection of curios, she seized a castle, and then rustled a number of animals from farms that she laid claim to in the Consett area. In January 1870, amid riotous scenes, she offered free beer all round as she auctioned off the stolen beasts – until she, eventually, was arrested.

Even to this day, no one really knows who Countess Amelia Matilda Mary Tudor Radcliffe really was – could she have been, as she claimed, descended from the 3rd Earl of Derwentwater who had lost his head in a Catholic rebellion? Or was the countess just a con artist who faked documents to claim an aristocratic fortune?

Or was she suffering a mental health condition with delusions of grandeur which convinced her that she was the rightful heir to the Radcliffe’s confiscated estates? The Daily Telegraph at the time labelled her rather cruelly as “a wandering lunatic”.

Her claim to much of north Durham was through James Radcliffe, the 3rd Earl of Derwentwater. In 1715, he was heavily involved in the Jacobite rebellion – a rising strongest in Scotland to place James Stuart, “the Old Pretender”, on the British throne and return the country to its Catholic ways.

The earl was arrested at Dilston Castle – now a ruin near the River Tyne between Corbridge and Consett – and taken south to meet his fate. It is said that his party broke their journey in the Bull Inn in Milburngate, in Durham, where he bashed his bounce on a low door lintel. “The head of Derwentwater will be much lower when he returns,” he said ruefully.

He was right. He was hung, drawn and quartered at the Tower of London, but when his remains were returned to Dilston, they were greeted by a spectacular display of the aurora borealis in the night sky – indeed, to this day, it is said that in north Durham the Northern Lights are known as “Lord Derwentwater’s Lights”.

His only son, John, was his heir, and became the 4th Earl, but he died unmarried aged 19 in 1831 in London in a horse accident.

The 5th Earl was Charles, the brother of the 3rd Earl, but he was beheaded in 1745 for trying to install “the Young Pretender” on the throne. All the Derwentwaters’ estates were confiscated and given to the Commissioners of the Greenwich Hospital in London, so that the income from the farms would go to run the hospital. Meanwhile, Dilston Castle, a medieval pele tower, fell derelict.

Nothing more was heard of the Derwentwaters for more than a century until Countess Amelia surfaced in 1857 with a few family heirlooms and a strange story to prove her connection.

She claimed that John, the 4th earl, was her grandfather. She said that he had faked his own death in that equine incident and been smuggled to Germany, where he had married and had a daughter – thus proving she was his rightful heir.

For ten years, Amelia pressed her claim in London, bothering everyone from Lord Palmerston to the Admiralty with her “proof”, without any success. Then, in 1866, she moved to Newcastle to be closer to the family estates.

In the North-East, she found a more receptive audience. There was a romanticism about the Jacobite rebellion; the Radcliffe family were looked upon fondly as decent landlords; there was growing dismay at distant London benefitting from the toil of County Durham farmers; there was sympathy among the Irish immigrant ironworkers in Consett – all Catholics – to a family that had fallen for supporting their faith.

On September 28, 1868, dressed as an Austrian soldier and armed with an unfeasibly large sword, the Countess marched into the ruins of Dilston Castle. She put up a tarpaulin to keep the rain out, and hung paintings of her ancestors from the walls.

The hospital commissioners evicted the squatter so she took up residence in a tent on the road outside. Thousands of people journeyed to see her large sword and express their sympathy and support until, on November 5, Hexham magistrates fined her 10 shillings for obstructing a highway and threw her out of her tent.

She turned her attention to the farms around Consett that her family had once owned. Brandishing her large sword, she would march into the farmhouses and tell the farmers to pay their rents to her and not the London hospital.

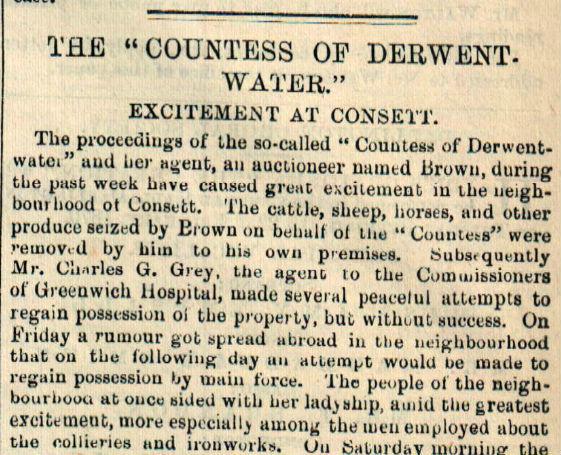

The bewildered farmers were reluctant to follow her advice, and so in January 1870, her henchman, Harry Brown, a bailiff from Shotley Bridge, went to Newlands South Farm, near Ebchester, and took all the cattle in lieu of rent.

The hospital commissioners sent up their agent, Charles Grey, to get the beasts back.

All Consett turned out exactly 150 years ago hoping the showdown between the countess and the commissioners would make an entertaining spectacle. They were not disappointed.

“The streets were soon thronged and the proceedings of the parties watched by an excited crowd, but as the cattle etc could not be found, owing to the precautionary measures adopted by Mr Brown, action had to be suspended,” reported the Durham Advertiser’s sister paper, the Darlington & Stockton Times, on January 22, 1870.

“Another event took place which kept up the excitement to a high pitch and this was the pre-arranged triumphal entry of the ‘countess’ into Consett.

“A proclamation was read declaring the ‘countess’ to be the heiress of John, the fourth earl, a statement which was received with tremendous cheering by the mob. ‘Her ladyship’ then entered an inn, and shortly afterwards bowed her acknowledgements from one of the upper windows.”

This was probably the Railway Inn, where the Countess bought beer for everyone, promising them even tastier freebies when she eventually inherited her estate.

Next day, Mr Brown successfully auctioned at least some of the rustled animals – 22 sheep, 11 heifers and two horses – in the streets of Consett.

Emboldened, he marched to the farm to sell off the fixtures and fittings.

“A large number of people proceeded to the farm at Newlands, for the purpose of assisting in the spectacle, dressed in blue and orange rosettes with flying streamers – they had a very odd appearance,” said the D&S Times.

The Countess was similarly attired, although she also had her “massive sword”.

Forty Durham police officers followed the mob – by now, about 4,000-strong – and 75 members of the Northumberland Constabulary were already stationed in the farm outhouses. The policemen cordoned off the farm, so Mr Brown stood on a cart and began auctioning all he could see over the hedges – the haystacks, the agricultural implements.

With purchasers wanting their lots, the crowds surged towards the hedge, lifting up Mr Brown so he crowd-surfed on the top of the mobs’ hands as they tried to tip him over the hedge. The police held him back, and then stones started flying and horses started charging…

“All along the road, the struggles went on with more or less vigour, but as the police succeeded in maintaining their position after every charge, the warfare was in a short time wisely discontinued,” said the D&S.

Sensing that the fun was over, the mob turned for home.

Over the next few days, the police picked off those who were there, and Mr Brown and the Countess were arrested. She was fined £500 for damage – about £60,000 in today’s values – and as she couldn’t pay, she was declared bankrupt and sent to a debtor’s prison.

The game was now up for the Countess of Derwentwater. She emerged from prison a broken woman with her public support evaporated. She died on February 26, 1880, of bronchitis in her home in Durham Road, Durham, and wished to buried in the Radcliffe family vault in Hexham Abbey. This was refused and instead she ended up in Blackhill cemetery, near Consett, where members of the Jacobite Society marked her grave in 2012.

There are many theories about the true identity of this extraordinary woman who for three decades pressed her case with a strength that persuaded thousands of people to join her for the ride.

Some say she was a schoolmistress who had read the history of the Derwentwaters and then skilfully set out to create the character of the countess. She bought antique picture frames, painted her own pictures of her ancestors and forged their wills as she drew up a convincing back story.

Others sources say that countess was really a lady’s maid from Dover or servant girl from the West Country, either deliberately fortune-seeking or genuinely suffering from mental delusions.

Or perhaps everything Lady Amelia, the Countess of Derwentwater ever said was completely true. Perhaps she really was the great-grand-daughter of the 3rd Earl of Derwentwater of Dilston Castle.

Whoever she was, exactly 150 years ago, the countess had convinced thousands of Durham people that she really was someone – even if her real claim to fame is that she was one of the greatest con artists and fraudsters he county has ever seen.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here