The only man to be burned at the stake in the North-East was Richard Snell of Bedale

AS dawn broke on September 9, 1558, it found four butchers hard at work in Newbiggin in Richmond. They had embedded a 10ft oak stake deep into the cobbles and were piling straw and twigs around its base. On top of the kindling, they sprinkled gunpowder, and then they liberally dolloped tar on top.

They were building a fire. They were going to burn a human.

The 16th Century must have been a deeply confusing time. One monarch forced everyone to convert to Protestantism; the next said everyone had to go back to being Catholic, and then the next forced everyone to be a Protestant which, as we told a fortnight ago, led to the Rising of the North exactly 450 years ago when scores, perhaps hundreds, of local men were hanged from roadside trees as punishment.

It started with Henry VIII who, in the 1530s and 1540s, broke from Rome, confiscated the Catholic monasteries’ wealth, and imposed the new Protestant faith.

But, in 1553, his daughter, Mary, ascended to the throne and bloodily re-imposed Catholicism.

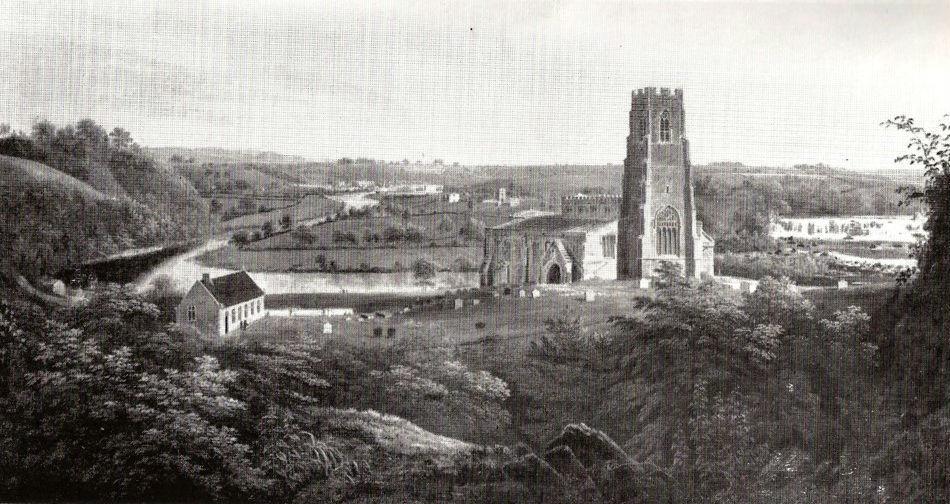

In the north, Dr John Dakyn, the Archdeacon of the East Riding and rector of Kirkby Hill, between Richmond and Ravensworth, was in charge of ensuring everyone was singing from the same Catholic hymn sheet.

Weavers Richard and John Snell, of Bedale, refused, and so were imprisoned in Richmond Gaol – a dentist’s surgery in a former police station at the west end of Newbiggin is now on the site of the jail. Conditions were so harsh that the brothers’ toes rotted off.

After 18 months, Dr Dakyn thought they had learned their lesson, and organised a service in St Mary’s Church where they could publicly recant. John played along, but Richard refused, shouting “sacrilege!” and “blasphemy” throughout the proceedings.

At the end, he was taken back to prison and John was freed. A priest made a walking stick for John from an elm tree outside the church and helped him hobble into the market place where he had found rooms for him next to Trinity tower. John stayed in the rooms for three days, coming to believe that he was a traitor to God and to his brother. On the fourth day, he struggled down Cornforth Hill and threw himself in the fast flowing Swale.

His body was washed up at Catterick Bridge four days later.

Dr Dakyn, a feared and powerful figure, summoned Richard to an excommunication hearing. “I'd sooner confess to a dog than a priest," he snarled, and so he was sentenced to burn to death.

At 10am on September 9, 1558, when the butchers had completed their preparations by bringing up a wagonload of green wood, he was manacled to the oak stake outside his prison cell. As Dr Dakyn spent nearly an hour reading out Richard’s crimes and heresies, the large crowd grew increasingly uneasy – the street vendors who’d brought food and drinks in the hope of making a killing did very little business.

Richard remained defiant, and when a prebendary thrust a crucifix in his face, he shouted: “Do your worst, false priest!"

Dr Dakyn gave the signal, and the butchers ignited the four corners of the pyre. As the flames took hold, they piled on the greenery, which shrouded Richard’s last agonising moments in a thick, suffocating smoke.

The crowd could still hear him, though. "Christ help me!" he shouted, but as the flames grew higher, his cries became incoherent until he emitted a last, piercing shriek and fell silent.

"A low, angry moan arose from the onlookers," says a contemporary account. "One voice, that of Richard Atkinson, a weaver, rang out loud and clear: 'Hold fast there and we will all pray for thee.' At these words many in the crowd sank to their knees."

Richard Snell was probably the only refusenik to be burnt at the stake in the Catholicly-inclined north. South of the River Trent, nearly 300 people were executed on Mary’s bloody orders.

Dr Dakyn fell ill the day after the burning, and he died on November 9 – exactly two months later, claiming he was choking on the smoke from Snell’s pyre.

And Mary died on November 17.

She was succeeded by Elizabeth I who turned the nation back to Protestantism. All Catholic symbols had to be publicly burned – those who refused, faced public humiliation. For instance, in Aysgarth, nine men had to walk to the parish church wearing only a sheet to do penance; at Manfield, the vicar and churchwarden were ordered to do penance in Richmond market place as their parishioners were hiding, rather than destroying, their items.

This led, in November 1569, to the Rising of the North. The earls of south Durham and north Yorkshire stormed Durham Cathedral to reimpose the Catholic faith, causing the Bishop of Durham, James Pilkington to flee, disguised as a peasant.

Then they marched south to take on the queen.

In Alice Barrigan’s marvellously detailed blog about the history of the Hutton Rudby area (northyorkshirehistory.blogspot.com), she tells how the rebels took oxen and sheep worth £111 6s 8d from fields at Whorlton, near Stokesley – afterall, an army marches on its stomach.

She also tells how the strength of the rebels deeply worried lawyer Thomas Layton, of Sexhow. He’d done rather well out Bp Pilkington, who’d made him the attorney-general of Durham.

On November 17, 1569, Layton set off on horseback from Sexhow, and rode across the moors in the night to York, where the Earl of Sussex was preparing the queen’s army to take on the rebels. He arrived at 3am with the worrying intelligence, and Sussex sent him back to raise a 200-strong army from Langbaurgh to defend Hartlepool, through which the rebels hoped to be supplied from the continent.

However, as we told a fortnight ago, the rising – the most serious in Elizabeth’s 45-year reign – soon fizzled out, and she executed many of those involved. Alice’s blog says that in Richmondshire, 1,241 men had joined the rebels and 231 were selected for the ultimate punishment, although many would have been reprieved if they had been able to give the queen enough money.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel