Back to the Land, we must all lend a hand,

To the farms and the fields we must go,

There's a job to be done,

Though we can't fire a gun,

We can still do our bit with the hoe.

THE 80,000 members of the Women’s Land Army apparently sang this song as, heigh-ho, it was off to work they went on the farms during the Second World War.

The army was formed in 1939 to enable women to work on the land where there was a shortage of hands due to men going off to fight at a time when self-reliance had never been more important.

Nowadays, we’d probably call these land army girls “lags”, but they didn’t live the cossetted life of today’s wags. They did all the physical jobs on the farm, for 50 hours a week. A quarter of them were involved in dairy work, and some of them formed anti-rodent squads as rats in particular were running riot.

Although they were centrally organised, the land girls were paid by the farmers for whom they worked. They got 28 shillings per week, 14 of which were deducted for board and lodging, and it was a rankle that the lowest paid male farm labourer was on 38 shillings per week. From 1943, the girls were allowed one week’s holiday.

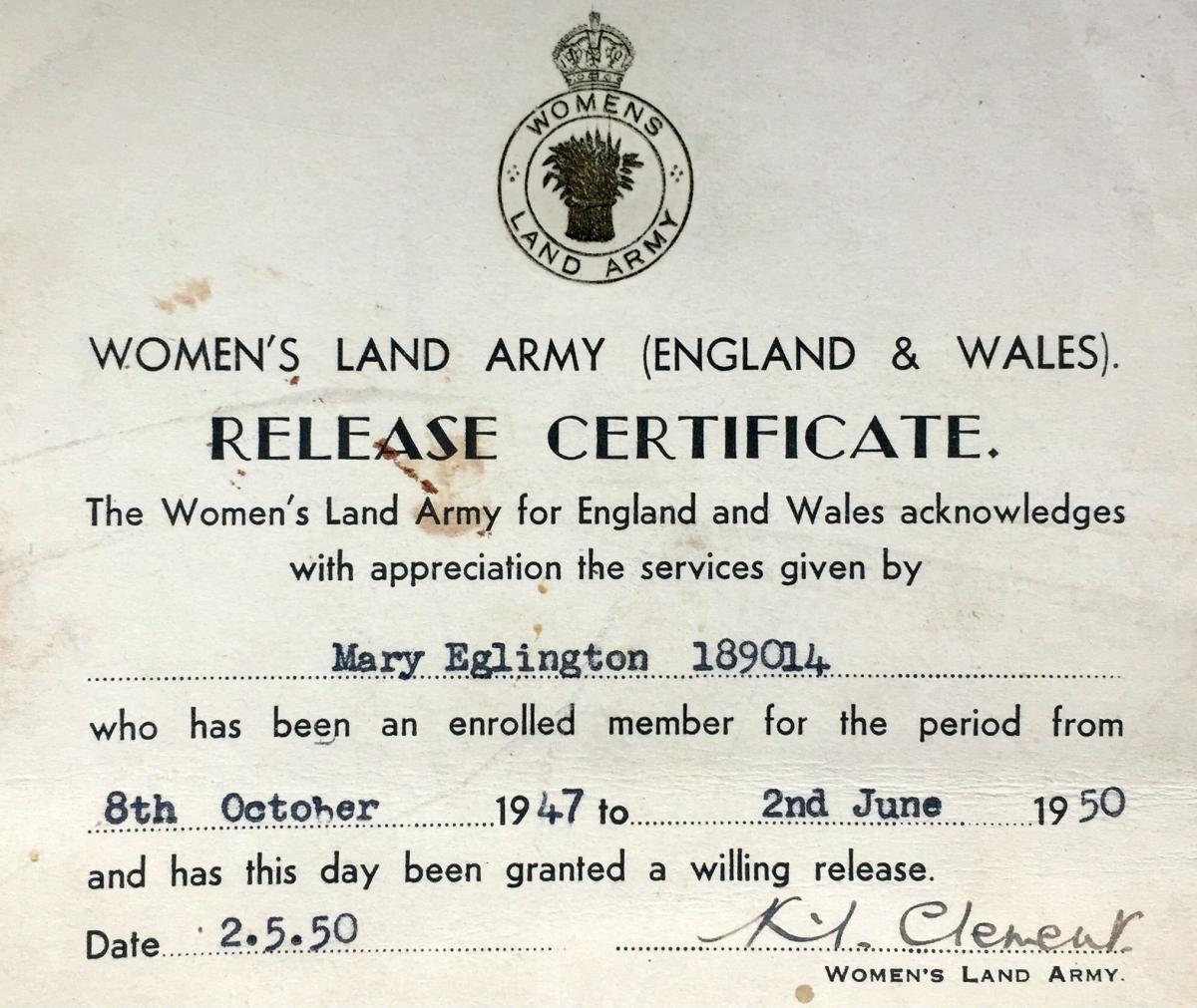

They wore a uniform of green jumpers, brown breeches or dungarees, a brown felt hat and khaki overcoats. All of them wore their land army badge with the emblem of a sheaf of wheat in the middle.

About 22,000 girls across the country lived in 700 hostels, such as the one beside the A66 at Sadberge which is now falling down. There were about 80 girls in the hostel, sleeping in iron bunk beds in two dormitories, fed by a kitchen block and supervised by a matron figure. They worked on the farms between Darlington and Stockton.

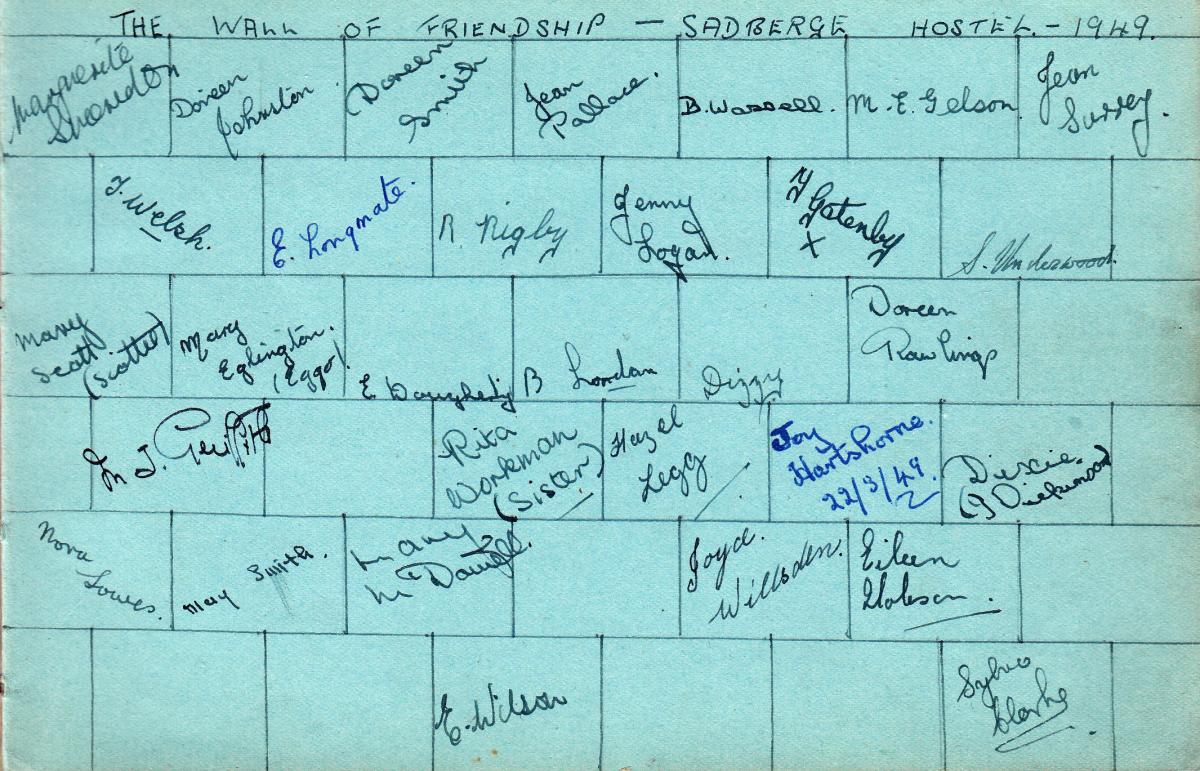

This hostel has featured in Memories recently as we were lent the autograph book of Joan Birtle, of Norton, who, at the end of her spell in 1949, collected the names of those with whom she had served.

One of those who signed her Sadberge “wall of friendship” was Mary “Eggo” Eglington, who will be 90 in March and still lives in Darlington. She hailed from Stockton, and joined up with a friend from Miss Ridley’s typing school when she was 17½ in November 1947.

The girls had to be in bed by 10.30pm each evening, except on Friday’s when they had a late pass, with many of them going to hops in Sadberge village hall or down to the RAF Middleton St George aerodrome.

Mary was also one of four girls from Sadberge who were sent down to Norfolk one summer for four weeks’ strawberry picking.

“They often got men prowling and looking through the window at the hostel and one night they decided to face this person,” says Mary’s daughter, Liz Blenkiron. “They armed themselves with shoes, and half way crept one way round the building and the other half went the other way and they met each other on a corner and frightened the life out of themselves.”

The WLA was wound down as the 1940s came to an end, and when Sadberge closed, Mary was transferred to a hostel at Wolviston for her last couple of months. There was another prowler complaint there and Mary, exasperated by her colleagues’ claims of seeing faces at windows, threw open a window to prove them wrong, only to knock a gentleman who happened to be passing off his bicycle.

Mary left the land army in June 1950 in time to marry Mervyn Hopper, and it wasn’t until 2008 that she, and all the other land army girls, received recognition for their service. The then Prime Minister Gordon Brown awarded them a medal and a certificate which told them that the “Government expresses its profound gratitude for your unsparing efforts as a loyal and devoted member of the Women’s Land Army”.

L Many thanks to Liz Blenkiron for her help

FROM Montego Bay to Marske by the Swale is a long way, but that is the journey taken by a “negro servant” who adopted the name of John Yorke when he settled in North Yorkshire.

He arrived in 1772 as a slave from a plantation in Jamaica when his owner’s daughter, Elizabeth Campbell, married John Yorke of Richmond. At some point, he adopted his new master’s name as his own.

But in 1772, a landmark court case resolved that it had never been legal to keep slaves in England. Some were set free; others remained tied.

By 1778, John Yorke was described as being “a negro servant belonging to John Hutton” of Marske Hall, near Richmond. The Marske parish registers show that on August 8 that year, he was baptised in the village church.

The register says he was “supposed then to be about 17 or 18 years of age and could say his catechism in a tolerable way”.

His was a rapid entry into the Church of England, because the day after his baptism, he was confirmed in Richmond church by the Bishop of Chester.

The Yorkshire gentry must have felt that John was a decent sort of a fellow, and that view was confirmed when he saved a gamekeeper’s life during a moor fire. As a reward, he was given his freedom and a cottage, and in 1799, he married a Yorkshire girl, Hannah Barker, at Kirkby Ravensworth church – the one high on Kirby Hill above Holmedale. They had seven children.

John Yorke’s story is one of those that researchers at the North Yorkshire County Record Office in Northallerton have been looking in to during Black History Month this October.

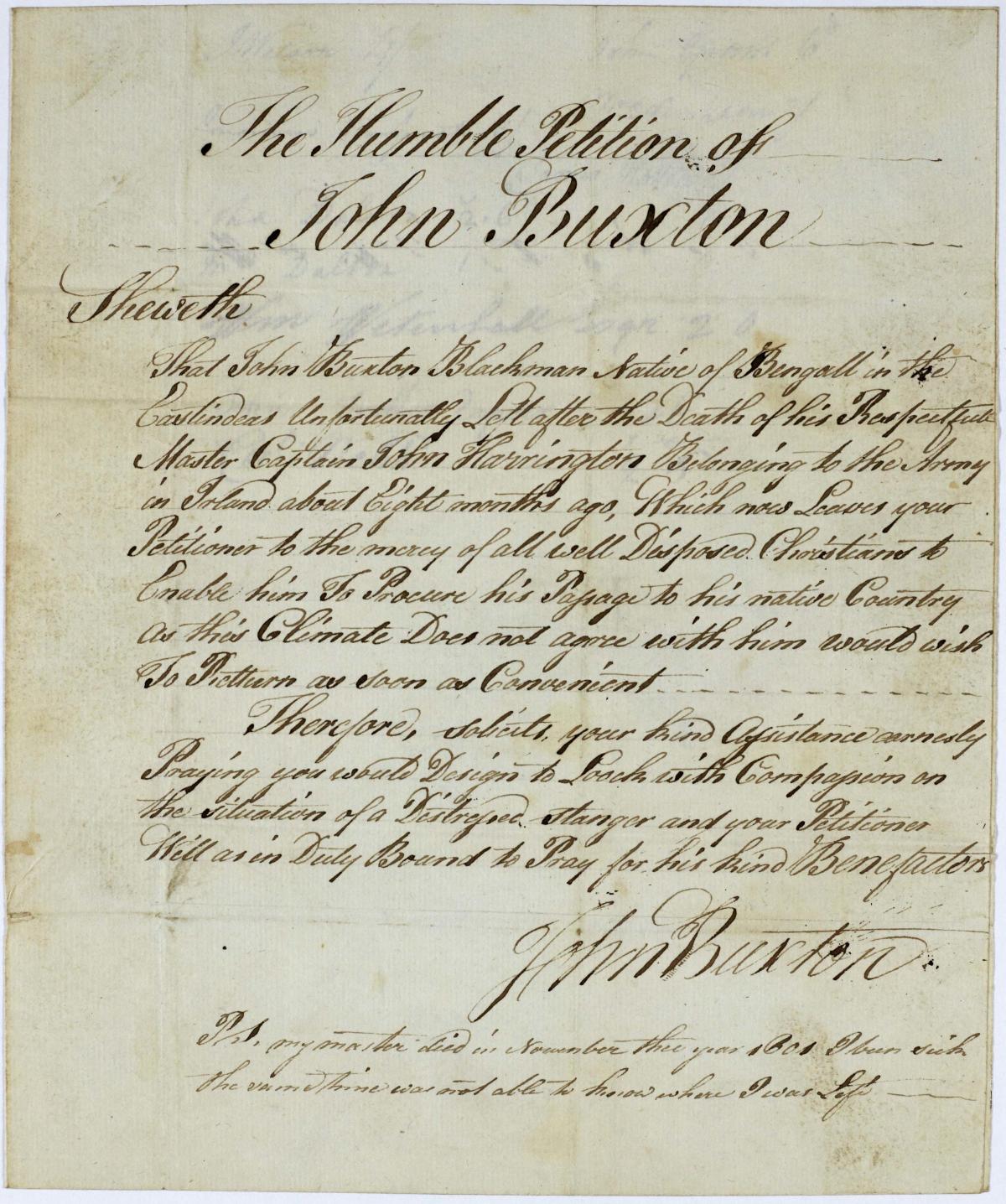

His story is quite well known, but the researchers indexing the quarter sessions court papers have unearthed other tales, like that of John Buxton “blackman, native of Bengall”, who was arrested for vagrancy in Thornton in North Riding (the papers don’t say which of many Thorntons) in 1802.

He had come to Britain with his master, an Army captain, who had suddenly died leaving him “to the mercy of all well disposed Christians to enable him to procure his passage to his native country as this climate does not agree with him, (he) would wish to return as soon as convenient”.

Another story concerns Paul de la Tuer, a “travelling Negro melodist”, who, in August 1869, was arrested in Richmond for stealing the pair of boots he was wearing. In custody, he explained that in his “common lodging house” in the town, he had been offered the boots for three shillings by Henrietta Smith, and had bartered her down to 1s 9d.

It was only when he was arrested that he had discovered that the boots had been stolen from innkeeper John Thomas Morton of Bedale. Henrietta was subsequently arrested for the crime and Paul signed his witness statement against her with a cross.

n To find out more about what the County Record Office has to offer, go to northyorks.gov.uk/county-record-office.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here