SIX hundred and 73 years ago today, the Durham countryside was filled with the sound of carnage as 12,000 Scots did battle along the banks of the Browney with 7,000 Englishmen.

Next weekend, the first Bearpark and Esh Community festival is taking place at Bearpark Workingmen’s Club. It will feature a display of paintings and posters from six local schools depicting the “Beautiful Browney Valley”.

On October 17, 1346, the valley was anything but beautiful. Earlier in the year, Edward III of England had invaded France with 15,000 men, provoking the French king, Philippe VI, to call on the Scots to invade England. Northern England, he claimed, would be a “defenceless void” because Edward’s army was all in France.

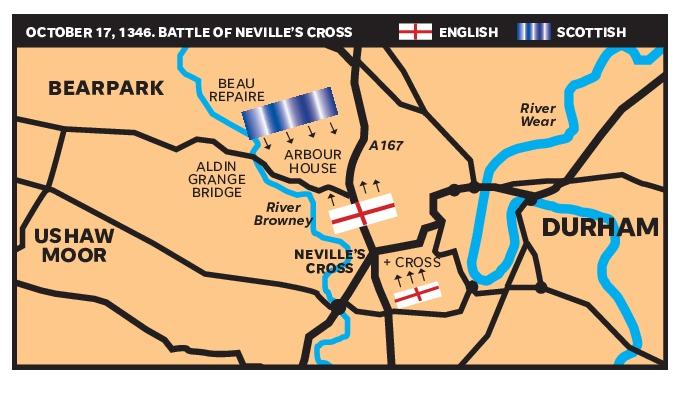

So on October 7, David II, the son of Robert the Bruce, invaded from Scotland, attacked Hexham Abbey and on October 16 arrived at Beau Repaire, the Prior of Durham’s “beautiful retreat”, to the west of Durham. The monks offered the Scots £1,000 to behave, but the soldiers camped out in the prior’s parkland, trashed his manor house and feasted on his game.

On the misty morning of October 17, they sent out a scouting patrol of 500 men under the command of Sir William Douglas which, to their great surprise, discovered an army of about 7,000 Englishmen advancing towards them.

The English army had been hurriedly recruited at Richmond by the Archbishop of York, William de la Zouche. With 3,000 men drawn from across the north, including 1,000 from Lancashire, he had marched to Barnard Castle where Lord Ralph Neville, of Raby Castle, had assembled another 3,000 men. Together, they marched northwards, and spent a night in the grounds of Auckland Castle – really, the Bishop of Durham, Thomas Hatfield, should have been leading the charge to protect the northern borders of England, but he was away fighting with Edward in France.

Early next morning, the English moved up to Kirk Merrington, a prominent hill south of Spennymoor. From there, they could secretly observe the Scottish army – and when the morning mist lifted, they spotted Sir William Douglas’ foraging party. They dived upon them, and chased them a couple of miles north up the A167 (the Great North Road) to Butcher Race, near Hett, where they literally butchered them, killing perhaps half of them.

Then the English marched over the Browney at Sunderland Bridge and up its northern bank to the outskirts of Durham City, where there was an Anglo-Saxon pilgrim’s cross. They took up a position on the high ground of Crossgate Moor, near today’s Durham Johnston School, straddling the A167 and looking down on the Scots on the other side of the Browney valley.

For a few hours, there was a stand-off, with the two armies staring at one another, unwilling to surrender their positions – for the Scots, the Earl of Moray had occupied an advanced position on the hillock of Arbour House.

The English longbow men provoked the Scots, picking them off with their arrows, until the Scots could take no more and charged. The Scots were expecting to find themselves attacking a makeshift army, but the English had some skilled archers in their ranks – probably the Lancastrians. The English also held the better ground, and they had a cavalry contingent, under Edward Baliol, hidden in reserve in what is now Neville’s Cross.

At first the Scots’ charge was successful, with fierce fighting along the ridge now occupied by Durham Johnston School.

But when the English cavalrymen were called up from the rear, the momentum switched, and the longbow men were able to pick off the Scots as they began retreating back into the valley.

Now the monks watching a mile away from the top of the cathedral’s central tower (presumably with very good binoculars) began to sing with joy. They were celebrating the Scots’ retreat and the survival of the relics of St Cuthbert which some brave clerics had taken from the cathedral to the schoolground where they stood steadfastly in prayer while the battle raged around them. For many years afterwards, monks would hold a cathedral towertop service on the anniversary of the battle, singing anthems to the north, the south and the east but not to the west as that was the direction the Scots had come from.

Back on the battlefield, perhaps the most decisive decision of the day was taken by the English who decided not to chase after the fleeing Scots on the flanks. Instead, they concentrated their fire on the Scottish centre, where David himself was.

The king was hit twice in the head and, with his men falling all around, he fled from the field.

With two arrows sticking from his face, he hid under the stone bridge over the Browney at Aldhin Grange on the road to Bearpark. The river must have been very still because he was betrayed by his reflection in the water. It was spotted by John Copeland, a Northumbrian, who dragged him out. David put up a fight, kicking out two of John’s teeth, but eventually the Scottish king was apprehended.

The defeat was now complete. Not only had the Scots lost their king, but up to 3,000 of their foot soldiers, and 50 of their noblemen, had been slain, with the English chasing the stragglers up to Fyndoune, near Witton Gilbert.

It was a rout. The arrows were plucked from David’s cheeks, although the tip of one remained embedded, giving him headaches ever after, and he was taken to the Tower of London where he languished for 11 years until the Scots agreed to pay a ransom of 100,000 marks (about £60m in today’s values), although they hardly paid any of it.

John Copeland was given such a big reward by Edward III for capturing the king that he was able to buy Crook Hall on the outskirts of Durham.

But with other soldiers, Edward was ruthless. Traditionally, victorious soldiers were able to capture their opponents and receive ransom money from their families in return for their release – it was a perk of soldiering. Edward wanted to quash the Scots, and ordered all captives should be killed. One English soldier who went against the king’s orders and ransomed a hostage was himself beheaded as a traitor.

Edward’s ploy worked. At the Battle of Neville’s Cross, the Scottish lost their entire military leadership leaving their nation undefended and so in the next year, the English led by Lord Ralph Neville were able to occupy over the border and up to the Forth.

This was the high point of Lord Ralph’s soldiering career. He had been fighting for king and country for 30 years, and a chronicler says he fought so bravely and powerfully in the battle that “his enemies bore the imprint of his blows”.

It is said that he returned to the scene of his triumph and replaced the old Saxon cross with a new one, “la Nevyle Croice”, which gives the battle its name.

Because the relics of St Cuthbert had played their part in the victory, and because Lord Ralph donated generously to the church, when he died on August 5, 1367, he became the first layman to be buried in the nave of Durham Cathedral, where he lies to this day.

Much of his battlefield has already been built upon as the city as extended westwards, and now the green fields between Neville’s Cross and Bearpark lie in the path of the proposed western bypass. With a little imagination, there are still lumps and bumps in the beautiful Browney valley that tell the story of the battle 673 years ago, and as you drive west to the first community festival next weekend, you will pass over the bridge beneath the Scottish king hid, shivering and bleeding with two arrows sticking from his cheek.

Bearpark & Esh Community Festival

Sunday, October 27: Bearpark Workingmen’s Club DH7 7AE

11am-4pm: Craft fair, stalls, children’s art exhibition, food

4.30pm-6.30pm: Folk music by the Elm Tree Band

7.30pm-9.30pm: Bearpark & Esh Colliery Band

Adults: £2

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here