THE 194th anniversary celebrations of the opening of the Stockton & Darlington Railway had a dampener put on them by torrential rain, but among the visitors to the area was Peter Heslop from Hampshire, who is a descendant of Thomas Storey, the railway’s first chief engineer. Peter would like to make contact with any Storey descendants – particularly if they have the Flintoff surname in their family tree.

Storey was born at Makemerich, a fabulously-named farm which is today near Newcastle airport, in 1789. He became a mining engineer and married a relation of George Stephenson. When Stephenson was placed in charge of the construction of the S&DR in 1821, he brought Storey with him as his resident engineer.

Storey was in charge of the stretch of line from Witton Park to Heighington Lane at Newton Aycliffe; he was also in charge of the Haggerleases branchline from West Auckland around the foot of Cockfield Fell.

Although the branchline was lifted in the 1960s, you can still see Thomas’ revolutionary Gaunless bridge – the world’s first skew railway bridge. Conventional bridges crossed rivers at 90 degrees and were held up by keystones; Storey pioneered a keystoneless method to cross the Gaunless at 27 degrees. It was so new that it is said that before building the permanent bridge, he tested a timber model of it in a nearby field – perhaps by stomping on it – and when the model didn’t collapse he built the real bridge in stone.

Having built the Merchandise Station in North Road, Darlington, in 1833, Storey surveyed the first stretch of mainline between Darlington and York, upon which he designed 77 small bridges, and he was the consulting engineer on the Shildon tunnel.

However, the inaugural train on the opening day of the mainline, January 4, 1841, was delayed by two hours as one of Thomas’ bridges near Thirsk collapsed onto the track. He “retired” soon afterwards, aged 52, and set up his own engineering business in St Helen Auckland.

One of his first projects was building a new row of houses off Newgate Street, opposite the Four Clocks, in Bishop Auckland. He called it Flintoff Street.

Why? In 1839, his daughter, Hannah, had married Theodore Flintoff and had emigrated to Australia where his grandchildren were born in the 1840s: Ellen, Owen, Eliza and Charles.

Their father, Theodore, either disappeared or died down under, and so Hannah brought her little Flintoffs back home to St Helen.

Thomas died on October 15, 1859, aged 69, and was buried in St Helen’s church, his passing overshadowed by the death three days earlier of Robert Stephenson, son of George.

But what happened to the Flintoffs? If you know, either contact railway historian John Raw – jraw2883@aol.com – or email Memories (chris.lloyd@nne.co.uk)

WE’VE long had an unhealthy interest in death by early railway. Memories 350 concluded that a blind American beggarwoman was the first confirmed person to be killed on the Stockton & Darlington Railway when, on March 5, 1827, she was “killed by the steam machine on the railway” at Egglescliffe. We’ve no idea how she stumbled under the wheels; we’ve no idea how she came to be so far from home.

However, we’ve long suspected that there were other deaths on the S&DR, and now archaeologist Niall Hammond has kindly pointed us in the direction of the Durham Advertiser of January 3, 1824, which reports on the death of a 14-year-old boy named Parkin, “belonging to Middridge”.

Young Parkin was in charge of two wagons coming down the line from Brusselton into Shildon (Shildon, the world’s first railway town, didn’t exist in 1824 so the location of the accident is given as East Thickley).

“He ran in front of them, with a view, as is supposed, to stop them, but being deficient in either skill or power, or perhaps both, he was unfortunately thrown down and instantly crushed to death, the wheels passing over him,” said the newspaper.

Poor chap!

The line was then under construction – in fact, the engineer in charge of its construction was Thomas Storey.

“I STILL use my Firth’s Stainless Steel Knife – it is the king of knives in my cutlery draw,” says Ena Gowland, of West Auckland, following Memories 441 in which there was a 1916 advert for Firth’s items which were being sold by the Darlington ironmonger, Sykes, in Blackwellgate.

“Neither rusts, stains, nor tarnishes,” said the advert. Ena’s has hardly aged, either.

“My knife has lasted two lifetimes,” she says. “In 1954, when I married and set up home, some of my late grandmother’s possessions were given to me: pottery, cutlery, cushions and pillows, all gratefully received.

“Being of good quality, most of these are still in use today – the tablespoon, with silver hallmarks, is now battered but still in service daily. The cushions, made by grandmother herself and stuffed with her own duck and hen feathers, are still on the go.

“These items are like keepsakes from long gone relatives. I wonder what today’s throwaway society will have left to pass on – everything seems to go to landfill.”

MEMORIES 442 featured a collection of Howden-le-Wear pictures which included a First World War postcard showing Private H Fowler dressed as a Red Cross nurse.

The rear of the postcard said Pte Fowler had been struck dumb on July 18, 1916, but had recovered his speech a month later on August 17. Speechlessness was a fairly common symptom of shell shock, and Pte Fowler’s recovery was apparently being promote as a hope-giving miracle.

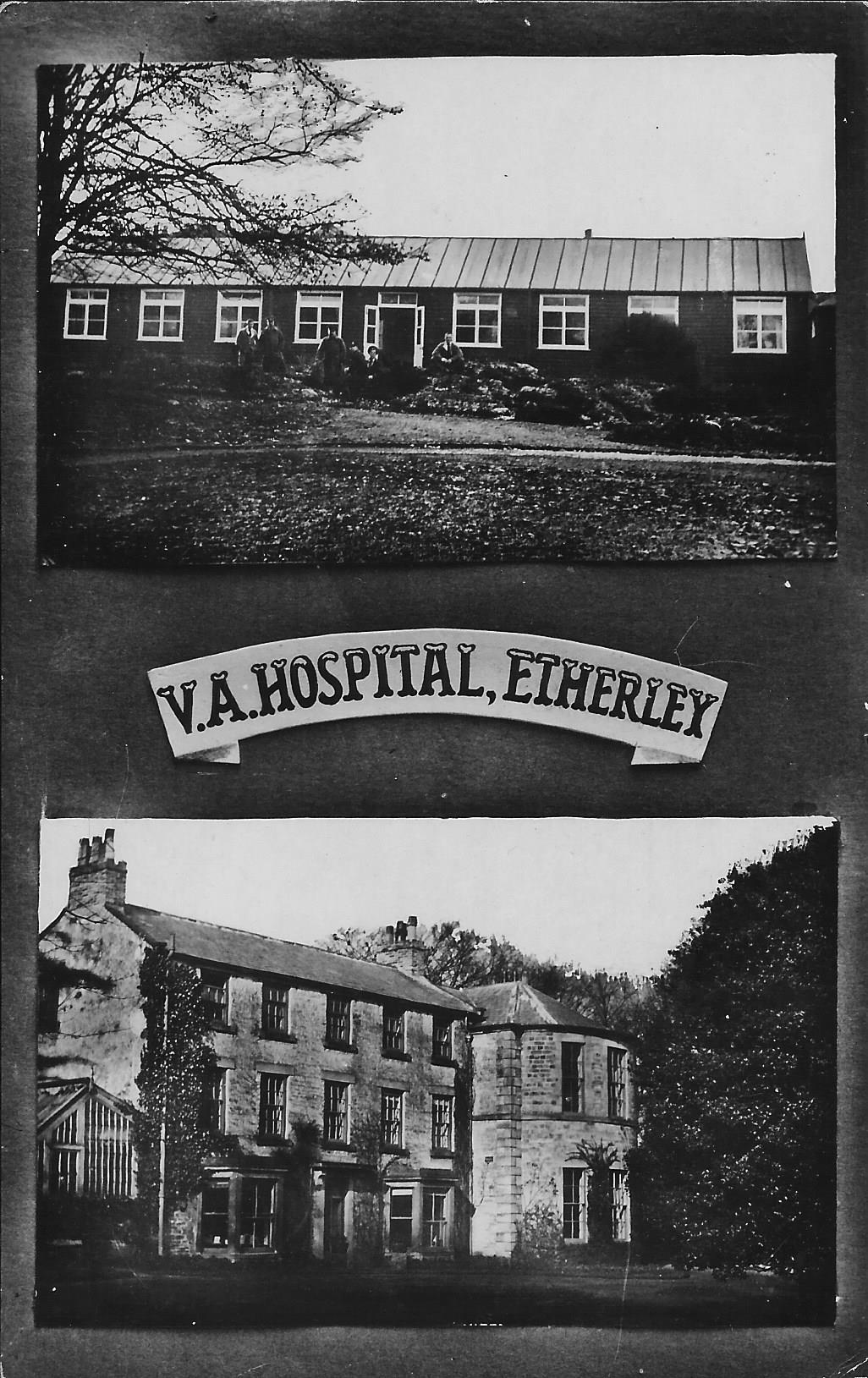

“I have a similar photo of Pte Fowler with the same inscription on the back,” says Kathleen Johnson in Barnard castle. “It was with a batch of photos from my mother, Mabel Simpson, from Billy Row who served from 1915 to October 31, 1918, as a Voluntary Aid Detachment nurse at the 17th Durham VAD hospital at The Red House in Etherley.

“I’ve always presumed that Pte Fowler was convalescing at the hospital.”

The Red House was a mansion belonging to mineowner Henry Francis Stobart, who offered it to the VAD as a hospital, and his wife, Jessica, became the commandant. The house was demolished after the Second World War and now a small estate of houses – called Red Houses – stands on its site.

So was Pte Fowler a local celebrity from Etherley?

THERE were howls of understandable outrage at last week’s Memories.

“I was staggered, nay, horrified, as a born and bred Yorkshire woman, to see your reference to “four ridings””, wrote Chris Eddowes.

Mike Masterman in East Cowton wrote: “Prior to local government reorganisation in 1974, administratively Yorkshire comprised three “ridings” (north, east and west) plus the City of York and not four ridings as stated in your article. I understand that the term “riding” meant a third.

“If there were four would they have been farthings?”

Our only defence, and it is a poor one, is that it looks like we started to write a sentence about “the four corners of the three ridings” but got distracted in the middle.

As all our knowledgeable correspondents pointed out, the Viking territory of Jorvik, centred on the city of York, was so large that it was divided into thirds – threthingrs – for administrative purposes. Over time, these had geographical descriptors added to their name – but as “north threthingr”, “east threthingr” and “west threthingr” are difficult to say, over time they lost the awkward sound at the beginning and just became the ridings.

The boundaries of all three ridings met at York, the capital of Jorvick, which was kept deliberately outside of the ridings so that it could be impartial.

The Vikings, under Ivar the Boneless, captured Jorvick in 866AD and by 954AD it had been subsumed into England, so although their heyday only lasted about 75 years, their three ridings have lasted more than a millennium.

As many people pointed out, the fourth riding only exists in fiction. South Riding is the title of a novel published posthumously in 1936, written by Winifred Holtby, a feminist, socialist, pacifist Guardian writer who hailed from the East Riding.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here