The blue sky shone above her,

The soft breeze floated by –

Where, on a stranger vessel deck,

She laid her down to die.

She heard the din of battle,

But she heeded not its roar;

For mortal care or terror

Could trouble her no more.

ANNA BACKHOUSE was just 28 when, caught up in an Italian revolution, she died on the deck of a British warship off the Sicilian coast and she was laid to rest in a cemetery beside her eight-month-old daughter who had died just weeks earlier.

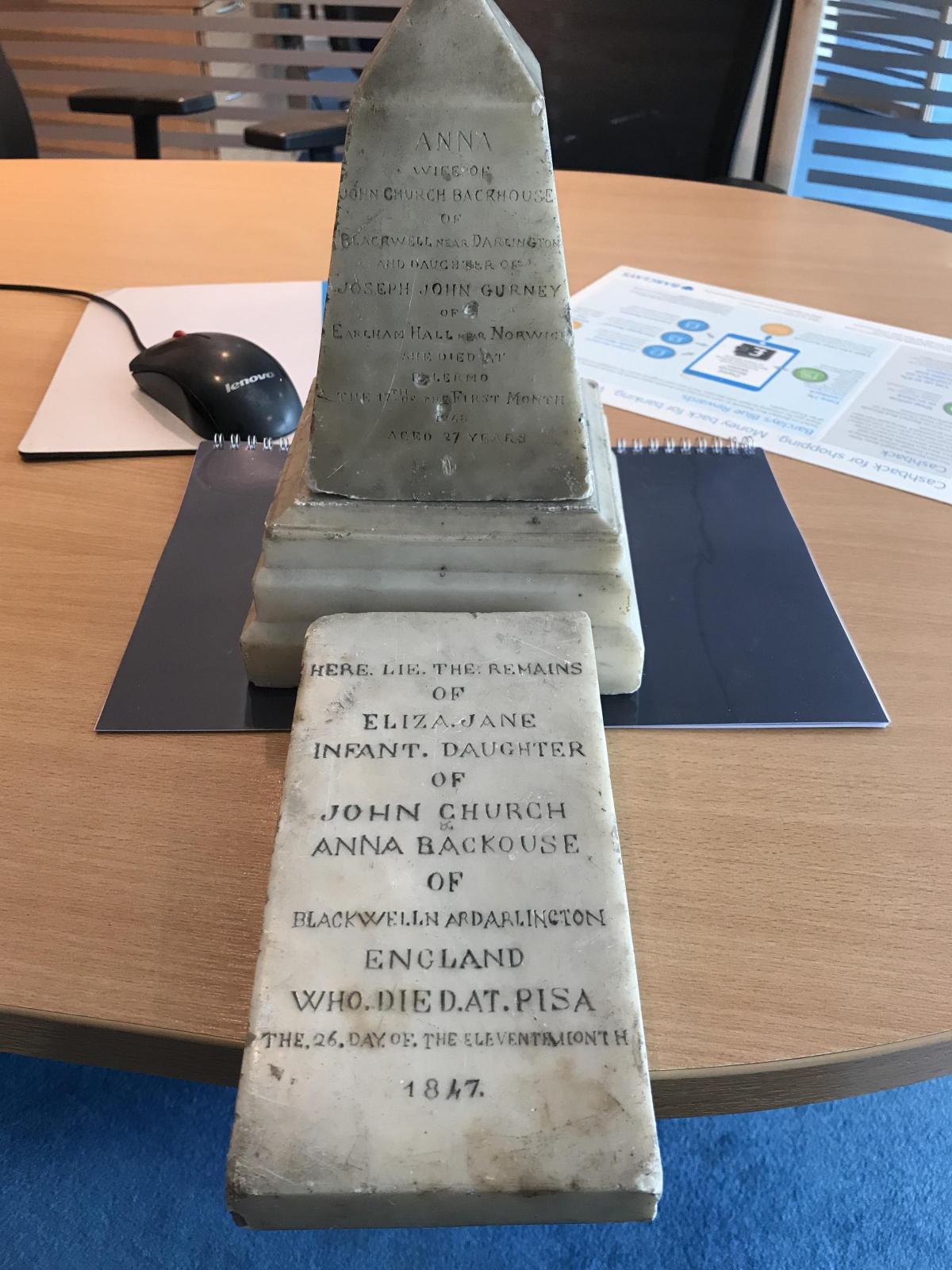

That was in 1848 in Italy. Next week in Darlington, her marble headstone will go on display at the Head of Steam museum having languished for decades unseen in a Darlington bank.

How the headstone came to be in Darlington, no one knows. How long it has been in Barclays – formerly Backhouses – bank on High Row, no one knows. Indeed, what the marble stone precisely is, no one knows. No one would have plucked Anna’s headstone from her grave in a famous cemetery in Pisa, so perhaps it is a replica for her family back home – yet the Italian carver has even spelled her surname incorrectly.

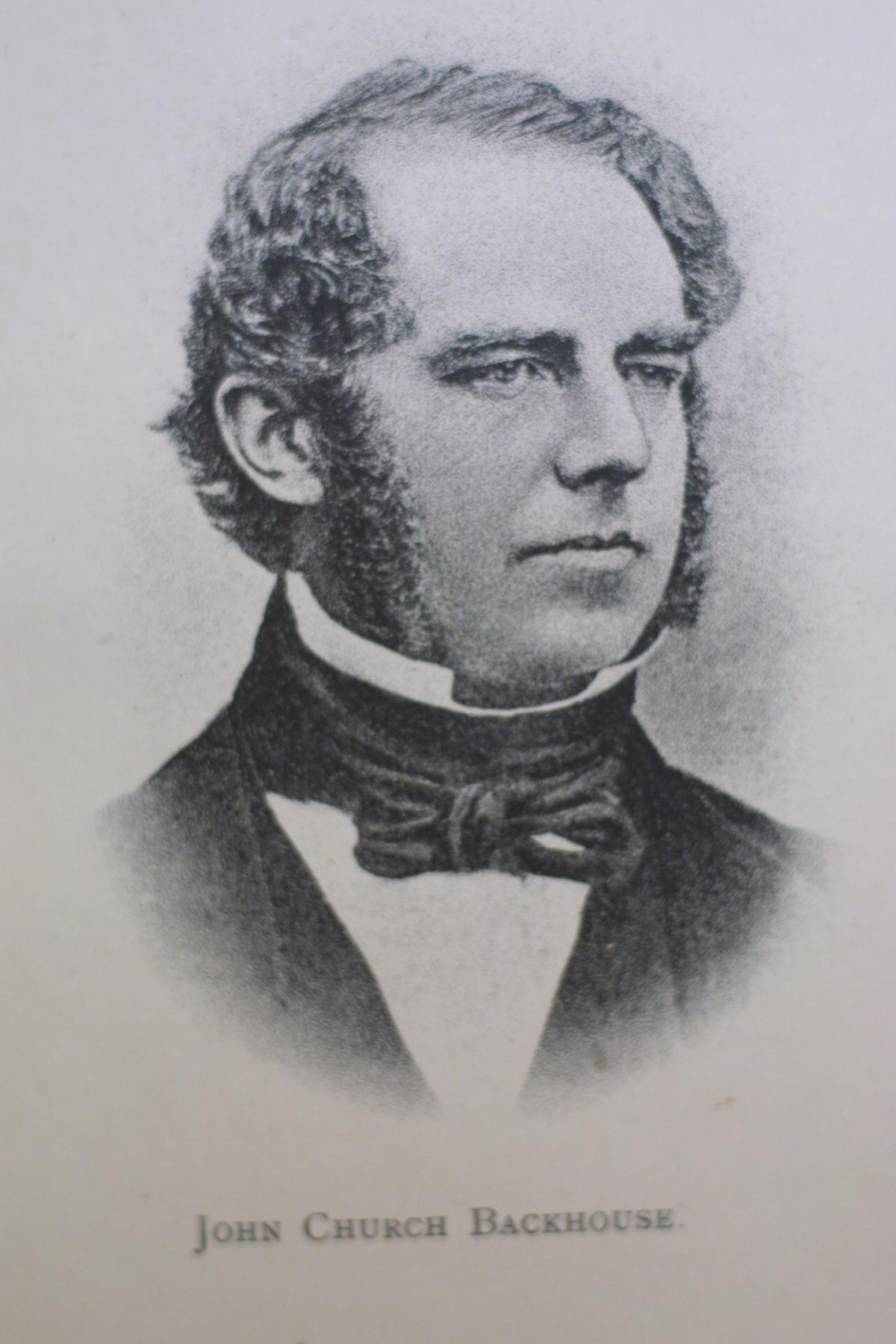

Anna was born in 1820 in Earlham Hall, near Norwich, into the Gurney family of Quaker bankers. In 1843, she married John Church Backhouse of the Darlington family of Quaker bankers. John’s uncle was the legendary Backhouse who balanced the cash on Croft bridge in 1819 and so saved the Stockton & Darlington Railway from the fox-hunting Duke of Cleveland, and John himself, aged 14, had been present at the railway’s opening in 1825. Indeed, some people hail him as the world’s first trainspotter because he had sent an excited letter to his sister trying to explain the wonders of the new form of transport which included a drawing of Locomotion No 1.

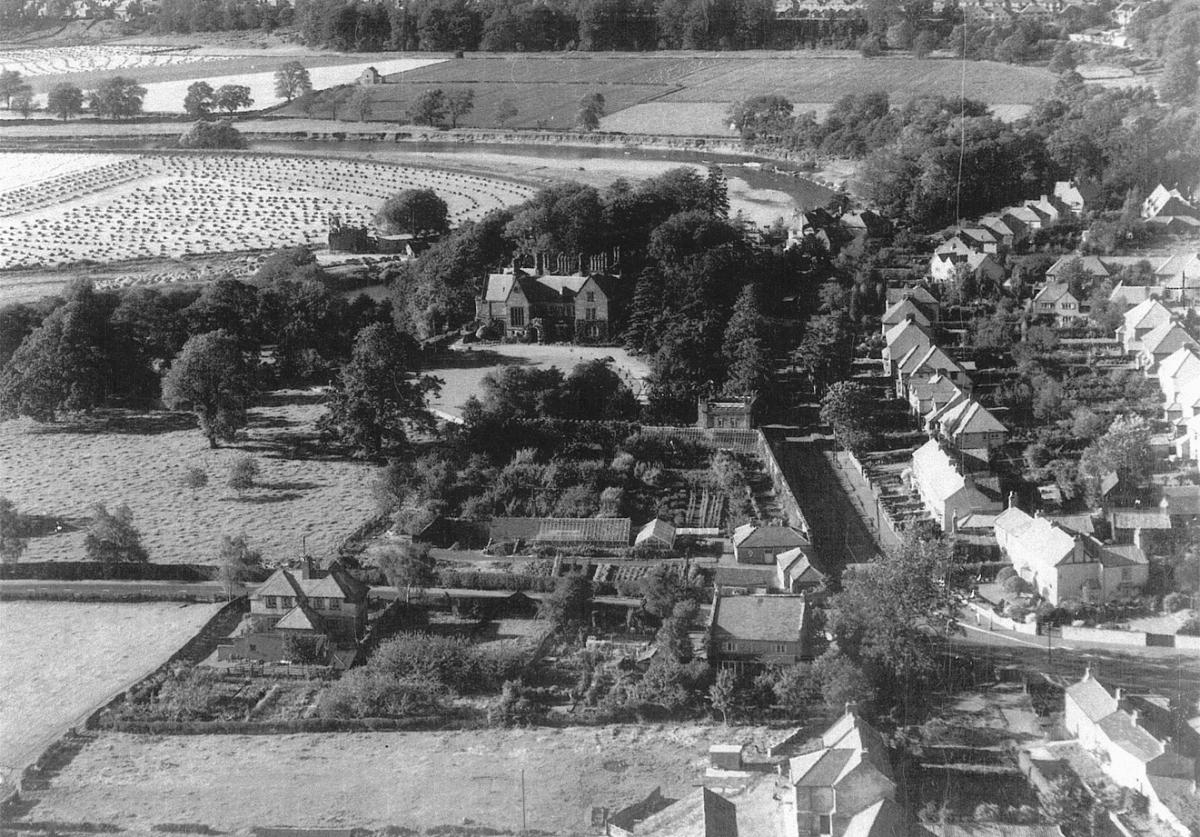

In 1843, after their marriage, John and Anna settled in Blackwell, on the edge of Darlington, in a house which is now beneath the Farrholme development.

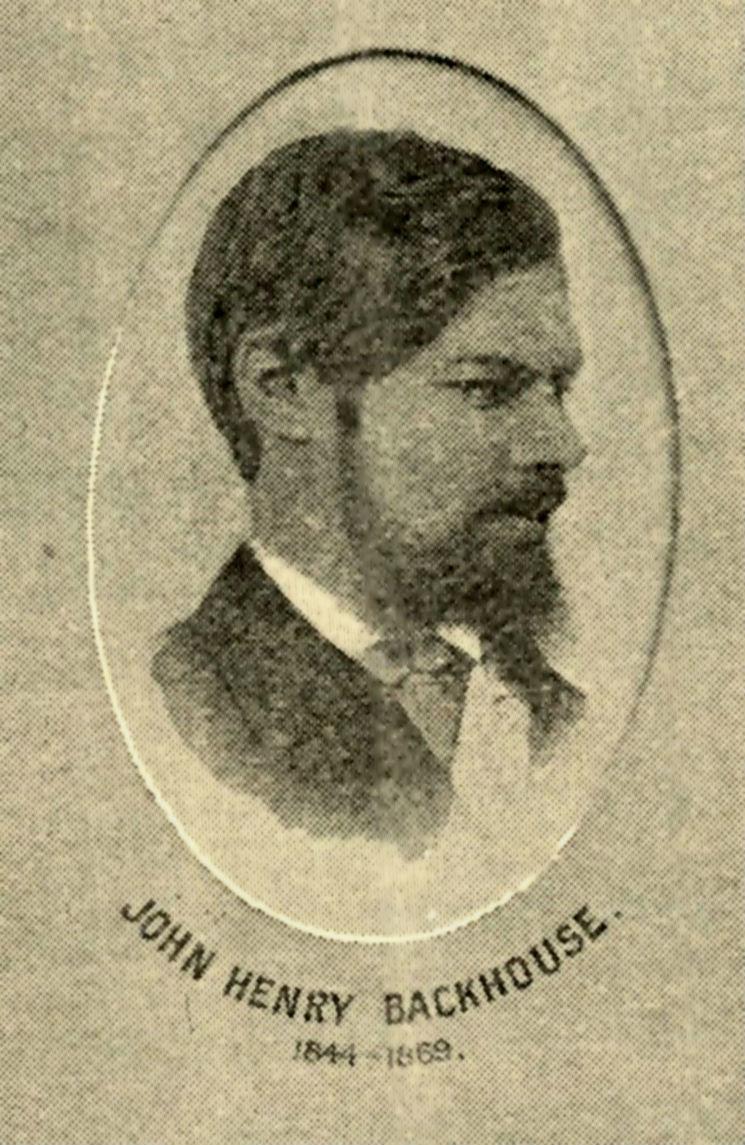

There, in 1844, she gave birth to a son, John Henry, and then on March 23, 1847, to a daughter, Eliza Jane. Mother and daughter were immediately unwell. They retreated to the Backhouses’ country residence of Shull, near Hamsterley, to recover. It had little effect, so they went to Anna’s family home in Norwich, where her “pallid cheek, her wasted form” was remarked upon.

But neither could Norfolk cure her consumptive cough, so John and Anna plus their two infants, and a retinue of three or four maids and men, headed for warmer, southern Europe. From Marseilles in south France they went to Pisa in northern Italy where, on November 26, 1847, baby Eliza breathed her last.

“I held her, dear little thing, on my lap as she rolled up her eyes once or twice,” Anna wrote back to her family, outlining Eliza’s last moments. “As she was lying on (maid) Sarah’s lap, her father and I watching her, she passed so quietly away that we could not detect the moment when she drew her last breath. We had a warm bath etc, but all was unavailing, and we were forced to believe at last that the life of our little one was gone!”

Near Pisa is the Old English Cemetery at Livorno (Anna refers to by its pidgin English name of “Leghorn”) where, since the late 16th Century, British adventurers, romantics, merchants, military men and artists had been buried. There, eight-month-old Eliza, from Darlington, was laid to rest.

Within days, Anna and John had moved on, seeking warmth as the last rays of the European sun ebbed away. “I am greatly afraid that the disturbed state of Sicily will prevent our going to Palermo, which every one unites in saying is much the finest climate for the early spring,” Anna wrote from Rome on December 14, 1847. “Every where else there seem to be such very cold winds…”

Down the boot they went to Naples, seeking doctors’ advice.

“We had a fine view of Mount Vesuvius burning the other night; the red lava pouring down its sides was beautiful, while the stars were bright above,” wrote John to his parents in the Beechwood mansion in Darlington (where Sainsbury’s supermarket is today).

Of his four-year-old son, he added: “Johnny wanted to know ‘when that burning mountain throws up stones, will they spoil the stars?’.”

But the cold of Naples brought on Anna’s cough. They found no alternative but to sail by steamer to Sicily, Italy’s most southerly point and so its warmest. And also its most rebellious – it wanted its freedom from the country’s Bourbon rulers.

Anna and John arrived there on January 12, 1848, and the Mediterranean warmth immediately improved Anna’s cough. However, on the same day, the Sicilian rebels rose up against that rulers.

They stayed in their hotel for three days, until the revolution endangered them and they sought sanctuary on a British warship, HMS Bulldog, which was in the area to keep an eye on British interests. Anna was carried on board in a chair by two sailors, and was joined by many other wealthy British health-seekers – Lady Mountedgeombe was reportedly present, although this may be a misreport as there is a Mount Edgcumbe House in Cornwall.

Anna rallied enough to take a walk on deck on January 16, but on January 17, she slumped. She said farewell to her maids and her husband, kissed little Johnny, put her faith in Jesus and noted that a warship’s deck was an unusual place to die. Then she died.

“My beloved Mother, I scarcely know how to write, or to find words to convey the tidings of the stunning blow with which it has pleased our Heavenly Father to visit me,” wrote John back to Darlington later that day. “My precious Anne breathed her last, on board this ship, this morning, about 12 o’clock!”

A couple of years after her death, a “brief sketch” of Anna’s life, covering 200 pages, was published for the family, including her last letters. It finishes with a poem by the Quaker writer, Rachel Cresswell, who concluded:

“Tis a strange place to die in,”

Were the words she calmly said.

She kissed and blessed her little child,

And her weary spirit fled.

The sun shines bright as ever,

The breezes softly blow –

All unheeded by the mourner,

In his solitary woe.

Poor John! He followed his beloved’s body as it was taken back through the revolution to the mainland and up to Pisa where it was laid to rest in the Old English Cemetery at Livorno. Also in there is the Scottish poet Tobias Smollett, the Durham City MP William Henry Lambton who died in Italy in 1797 of consumption, a Tory politician called John Pollexfen Bastard and, of course, Anna’s baby daughter, Eliza.

John and his son came back to Blackwell. John’s sister, Eliza Barclay (she had married into another Quaker banking family but had been widowed after just eight months of marriage) moved in to help out.

In 1851, John, a partner in the family bank, was one of the leading Quakers who created Darlington’s South Park – the first municipal park in the North-East – but he died in 1858, leaving his son a 14-year-old orphan. Eliza became his guardian, even moving to London with him when he went to study archaeology, history and philology at university.

He graduated, they moved back to Blackwell and he took his first steps into public life, elected as a Guardian of the Poor, and then he died aged 24 in 1869 of congested lungs – much like his mother.

And there the story ended until 150 years later, Sue Theobald, the new manager at Barclays bank in High Row, was going through some cupboards and discovered the marble stones bearing the names of Anna and Eliza Backhouse.

Distinctly unQuakerish, how they came to be there is anyone’s guess, but on Friday, they are due to begin a month-long stay at the Head of Steam museum.

If you know anything about the stones, we’d love to hear from you…

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel