BACKSTONE BANK is a 100-metre, lung-busting climb above Tunstall reservoir in a forgotten fold of Weardale.

From the farmhouse at the top of the bank, there are magnificent views back over Wolsingham to a strange, stand-out thicket on the daletop known as “the elephant trees”.

Climb higher still onto the moors and you come across the trackbed of the old Darlington to Consett railway, along which on August 20, 1878, a special train of first class carriages brought “fully 100 ladies and gentlemen” up from Crook.

They hadn’t come to admire the fabulous views. Instead, they had come to inspect the amazing waterworks in which they, as shareholders in the Shildon and Weardale Water Company, had invested.

First, the luxurious train wended its way from Crook up to Tow Law and then higher still, past Backstone Bank and beyond Saltersgill Cottage (where the railway had probably built a passenger station but never opened it as they were no passengers on this inconceivably remote ridge of County Durham) to Waskerley, where the company’s large reservoir had been completed in 1877.

“The party spent a lengthened time in inspecting the reservoir and its charming surroundings, and only one opinion was expressed as to the perfect fitness of every portion of the work,” said The Northern Echo the following day.

Having seen enough of the perfect Waskerley reservoir, they retraced their tracks.

“At one o’clock, the party re-entered their special train and proceeded to Backstone Bank, where a large marquee was erected and a sumptuous luncheon in readiness,” said the Echo, as if it were an everyday occurrence that a feast could be served in such a location.

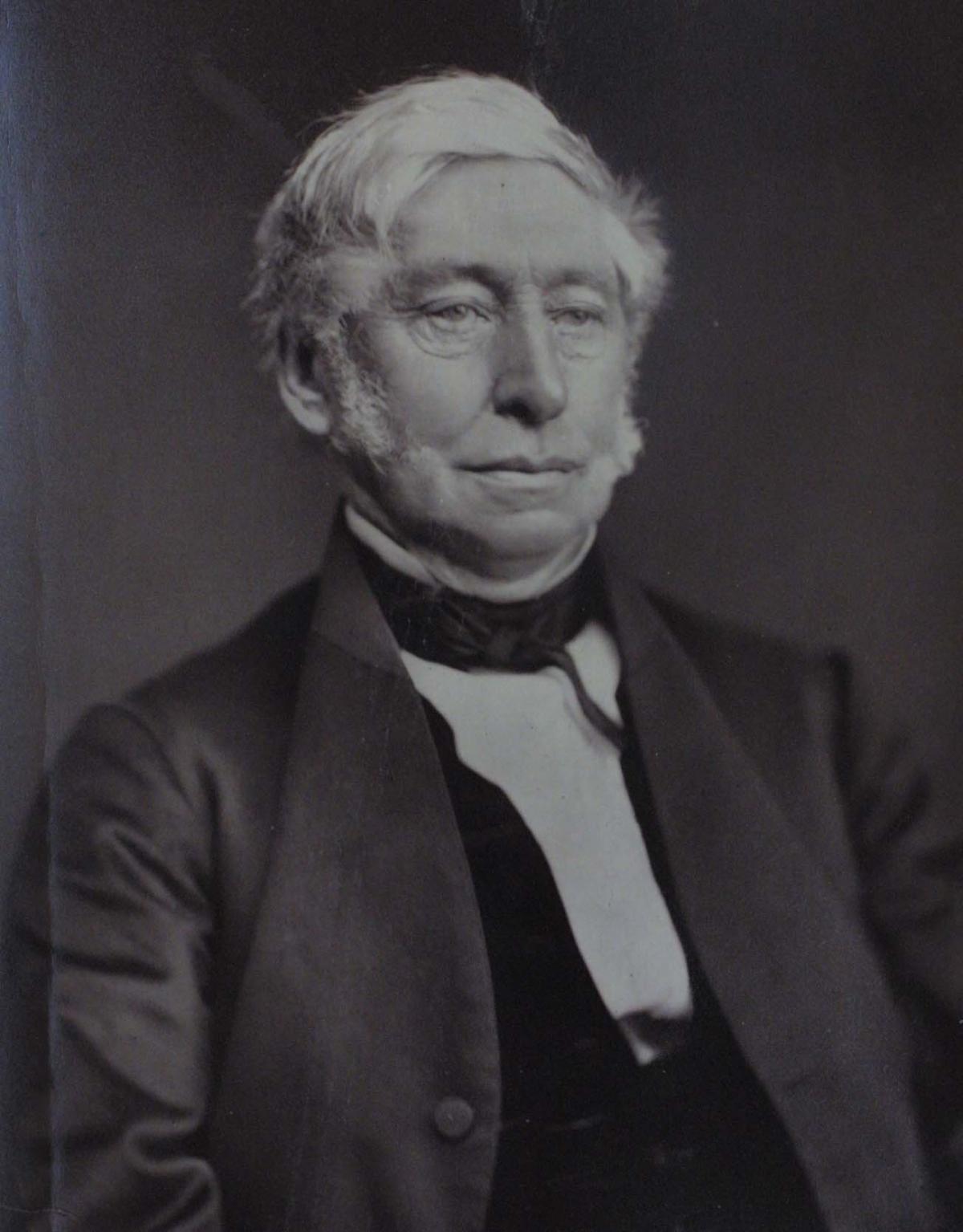

“Agreeably to the tastes of all the guests, formal toasts and speech-making was not indulged in,” said the Echo, although the company chairman Henry Pease did say a few words.

The Darlington railway entrepreneur, who also created Saltburn, said that Tunstall reservoir beneath them would soon hold one thousand million gallons of pure water – far more than Waskerley – and, tellingly, “he expressed a fervent hope that prosperous times might return ere long”.

With Mr Pease on the water company’s board of directors were other Darlington leading industrialists. He was accompanied by his nephew Arthur Pease, the MP for the town, and his nephew-in-law, Theodore Fry who would soon become Darlington MP. Alfred Kitching, the founder of the Whessoe foundry, was another leading light, and the reservoir had first been engineered by locomotive builder Thomas Bouch.

He, though, had died in 1876, and the directors had called in Thomas Hawksley, a Nottingham man who was one of the most eminent water engineers of the day.

Which was a good thing because Tunstall was tricky and expensive. In February 1876, The Northern Echo reported that the company hoped to complete the reservoir’s construction that year, but two-and-a-half years later when the trainload of concerned shareholders turned up, it was still only “almost completed”.

One of the difficult days in the construction came on August 13, 1877, when driver William Locks, who was working on the dam, was killed. The Echo said he “was riding on a waggon on the embankment, when the horse commenced to trot. He leaped off, and fell across the rails, the waggon passing over his body. He died shortly after.”

The biggest delays were caused by the discovery that the natural rock beneath the dam was not watertight and so the water in the reservoir was oozing out. Mr Hawksley had to invent a new technique called “pressure grouting” in which he injected into the rock grout under such high pressure that it spread out and filled all the natural pores out of which the water was leaking.

This technique pioneered at Tunstall has been employed in practically every dam ever built around the world ever since.

So in that marquee on Backstone Bank, Mr Hawksley, as the hero of the hour, received “reiterated calls from the guests” to say a few words. He responded by “congratulating them on their prospects of earning solid and lasting dividends”.

Then he invited them to walk down the steep bank and inspect the literally bottomless pit that was eating up their money.

The guests walked around the reservoir and “for strength and completeness (it) was considered most satisfactory”, said the Echo.

“This inspected, the party reclimbed the hill to the railway station, and returned by ordinary train homewards, very tired but very pleased and satisfied with a happy and enjoyable day’s outing.”

Very tired! That must be an understatement. After a “sumptuous luncheon” no one can climb Backstone Bank and be merely “very tired”. Utterly exhausted would be a better way of putting it.

Initially, the reservoir supplied the people of Shildon and Weardale with drinking water. In 1920, the Peases’ private company was taken over by Durham County Council’s new water board. Public ownership finished following privatisation of the water industry in 1989, and Tunstall is now owned by Northumbrian Water. In 2004, the reservoir stopped supplying drinking water and now maintains the water level in the River Wear.

Thanks to Doug Morrison, who grew up in Tunstall, for pointing us in the direction of the reservoir

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel